A few years ago, Mark Adams was diagnosed with colon cancer. His doctors didn’t want to operate, he said, because his recovery could be too risky without a clean place to recuperate. He was living on the street.

Soon, it was too late, his cancer too far along. That’s what they discovered after he moved into Welcome Home, a facility offering long-term medical respite and end-of-life care for unhoused adults.

Instead of getting better, he’ll likely live out the rest of his days there – one of a small number of places in the United States that offers unhoused people a comfortable and dignified option when they are terminally ill.

Sufficient end-of-life care in the United States is a growing problem for the general population, as America’s aging baby boomer generation needs more intensive and expensive help and supply isn’t keeping up. For many unhoused adults — who frequently lack a strong social safety net — long-term medical or hospice care are effectively inaccessible. In the absence of publicly funded solutions, private organizations and nonprofits are trying to plug the gaps, but the patchwork network of end-of-life care homes is far too limited to address the need.

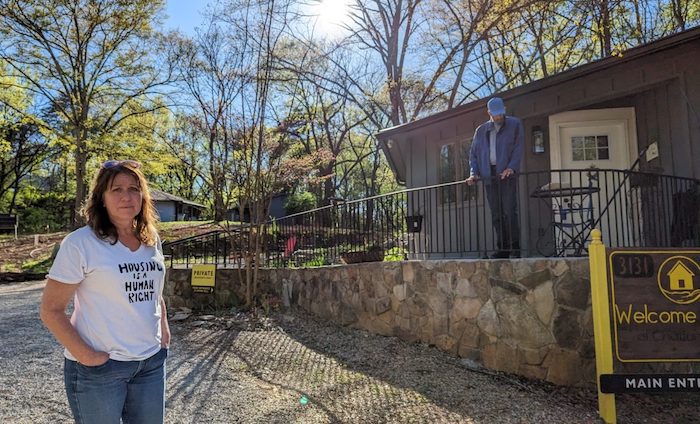

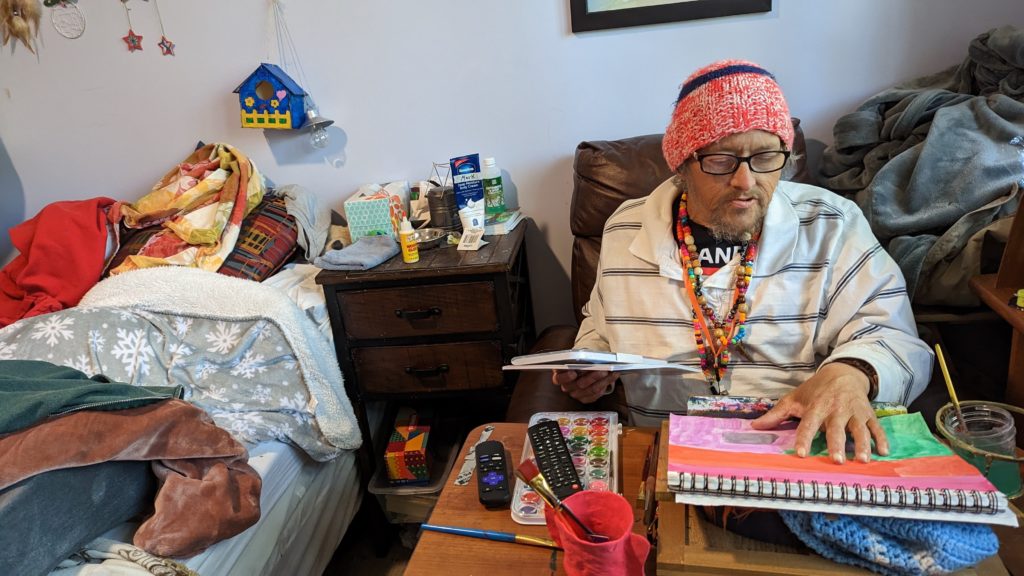

On a mild spring Sunday, Adams worked on a painting in his cozy, eclectic room – filled with vinyl records, potted plants and his own art – while his friend Clint Jackson relaxed nearby. Up the hill, Standrew Parker rested on a wrought iron chair in his yard, soaking up the early afternoon sun and chatting with his new roommate, Heidi Motley. Parker, 40, and Motley, 58, are staying there while undergoing treatment for cancer.

Across the country, there are a handful of facilities like Welcome Home, which sits on nearly five forested acres in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Some 1,300 miles west, there’s Denver’s Rocky Mountain Refuge for End of Life Care. Salt Lake City is home to The Inn Between, while Washington, D.C. has Joseph’s House. In Sacramento, Joshua’s House plans to open its doors this fall. Dozens more offer medical respite beds, generally for those undergoing long-term medical treatment. But outside of these organizations, experts told the PBS NewsHour that there are few other places where people experiencing homelessness can go for end-of-life or hospice care.

These facilities aren’t massive – Welcome Home has three medical respite rooms in addition to its four hospice beds, and is opening another house with an additional three rooms this month. Rocky Mountain Refuge, the smallest and newest of the group, has three beds solely for end-of-life care.

The need for those beds is great: People who are homeless are at far higher risk for many illnesses and conditions, such as heart disease. Medical research also shows that unhoused people’s bodies have often aged as if they were at least a decade older.

Being without a home is itself “a life-limiting diagnosis,” as Hannah Murphy Buc, a researcher who studies palliative and end-of-life care for people experiencing homelessness, wrote in the journal Caring for the Ages.

When someone is already in poor health, there are basic obstacles of living without a home – not having access to a fridge to store medications or the ability to secure narcotics for pain management, for instance. Some people without permanent addresses, like Adams, have reported they were denied treatment for their cancer due to the physical demands of recovery.

“Hospice and palliative care, but particularly hospice, is completely reliant on having a place to receive it,” Murphy Buc told the NewsHour.

For Adams, 51, living at Welcome Home has been life-changing, even though he often feels sick and he says he knows the cancer will likely kill him.

“I feel good here. I feel like I’m welcome here,” he said.

What we know about deaths among the unhoused

There is no official national data on where, when and how people experiencing homelessness die. According to an analysis by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC), at least 5,800 people died while experiencing homelessness in 2018. That’s almost certainly an undercount, and the report noted the actual number could have been anywhere between 17,500 and 46,500 deaths for that year.

With more people expected to become homeless and as that population ages, that mortality figure expected to rise, said Dr. Margot Kushel, director of UCSF’s Center for Vulnerable Populations and Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative.

“The truth of the matter is most of the country is entirely unprepared for this,” Kushel said.

Local reports can help explain what’s happening currently to those who can’t access end-of-life care. Across several months in 2021, deaths among unhoused people in San Francisco occurred primarily outdoors, in places like encampments, vehicles or on the street, a report from the NHCHC found. Others died in medical facilities; motel rooms, either rented by the person or as a shelter-provided space; other people’s homes; and homeless shelters.

Similarly, in King County, Washington, about half of the people experiencing homelessness who died in 2018 perished outdoors, according to a report from the council. Only 26 of the 194 deaths occurred in residences.

A 2022 report from the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless found that among the unhoused individuals who die of so-called “natural causes,” 30 percent died in hospitals or other medical facilities, and 25 percent died outside.

“That means under a bridge, on a sidewalk, behind a bush, in a tent,” said Brother James Patrick Hall, the executive director of Rocky Mountain Refuge.

While in prior decades people experiencing homelessness may have died from acute causes, such as violence or illness, the aging population of unhoused people is now living with the chronic conditions that plague many seniors, such as COPD, heart failure, strokes and cancer.

“These folks often need a lot of personal care. They have pain issues … It’s like a disaster, to be honest,” Kushel said. “What we found in Oakland is [that] a lot of folks just died on the street, short of breath, in pain, incontinent.” Others were admitted to hospitals, and some ended up at nursing homes or acute care facilities, “but it wasn’t where they wanted to be.”

When given a choice, people overwhelmingly want to die at home, according to Murphy Buc. Death at home can lead to healing in relationships and help soothe those left behind. But even when that’s an option, it can be draining for those doing the caretaking, she noted, even with hospice nurses visiting a few times a week.

In the U.S., “we don’t do death well,” Murphy Buc said.

The problem of older people dying on the streets, in motel rooms and in cars is the ultimate result of disinvestment in affordable housing, skilled nursing care and health care, experts at the NHCHC told the PBS NewsHour.

It’s not that people who become homeless are falling through the cracks, said Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy at the NHCHC. Instead, people are often forced into “gaping caverns” where underfunded social safety nets, such as Medicaid and public housing, fail to catch them.

An older adult who has worked as a manual laborer her entire life might have a stroke and lose employment, be unable to pay rent and end up without a home, said Caitlin Synovec, senior program manager with the council’s medical respite team. Shelters frequently can’t help people with enhanced medical needs, so they have nowhere else to turn.

The unhoused population is also disproportionately vulnerable, low-income and people of color — all groups who have historically experienced disparities and may distrust the nation’s health care and social services systems.

In addition to that added barrier, people may just not know they have medical respite and end-of-life care options, Murphy Buc said. Many of the current residents of these facilities were referred there by health care professionals or social workers, but had not previously heard of them.

‘Health care isn’t housing’

Having a home, in and of itself, can be considered a form of health care, advocates say. Those who work or volunteer at care homes sometimes witness very sick people make dramatic recoveries simply because they have a safe, comfortable and stress-free place to live.

Though each facility operates slightly differently, these homes offer more than just a physical address, providing services like palliative care, case management and transportation. Volunteers and staff can remind residents to take medicine, ask how they’re feeling, and, crucially, drive them to appointments.

Before Standrew Parker lived at Welcome Home, he would have to travel to the hospital from his mother’s house to receive five days of cancer treatment every few weeks. In addition to being an unwelcoming environment, her house was about 45 minutes away by rideshare, which cost around $60 to $70, he said. To avoid the trip back and forth, he would instead often spend his days living outside the hospital.

“We didn’t have that money. So I was in and out, just like hanging out. If I had multiple appointments for days on end there, I just [stayed outside the hospital]. I would have to or I wouldn’t get the correct shots or the treatment,” Parker said.

Now, volunteers drive him to and from his treatments, and during his weeks off from chemotherapy, he recuperates in his room at Welcome Home. Beyond the care he receives, the empathy and compassion from staff and volunteers helped shift his entire perspective on healing.

“It’s like a world of difference between surviving and actually being able to get well,” he said.

A crucial goal of each facility is to establish a sense of normalcy for people whose lives have been thrown out of balance. Welcome Home serves dinner every night, where residents can gather and rib one another. People living at The Inn Between can join the resident council, which offers both community and a way to effect change, such as what times coffee is available. For the patients who recover enough, these homes can help them adjust to life outside of the facility so they can leave.

When NHCHC began their medical respite programs in the late 1980s, they were originally intended as short-term stabilization. However, some of the programs that specialize in medical respite have begun to consider incorporating end-of-life and hospice care into their models to fill the gap, said Julia Dobbins, director of medical respite at NHCHC’s National Institute for Medical Respite Care.

In contrast, patients without somewhere to go sometimes cycle between a hospital and the street, being readmitted when their problems are acute enough to warrant immediate care, and released when they’re stabilized, Murphy Buc said.

Sending still-sick people back to the streets is called “patient dumping,” and “it’s horrible,” Kushel said. But, she added, the solution can’t be that people live at a hospital for months on end until they die. That’s an inefficient use of resources, not to mention that it’s unlikely to be where a patient wants to spend the rest of her life.

Hospitals don’t want to deny people care, Kushel said. When she heard about Adams’ doctors refusing to treat his cancer while he was experiencing homelessness, she noted that his situation was not uncommon. Doctors worry about harming people who don’t have access to long-term, safe and clean care, but it doesn’t make it an easy decision.

“It happens all the time,” Kushel said. “And when you speak to the surgeons, they actually feel terrible about it.”

In the long run, even medical respite doesn’t solve the problem of where people can live, said NHCHC’s DiPietro.

“We often say housing is health care. Absolutely,” she said. “Unfortunately, health care isn’t housing.”

For many, providing medical respite or end-of-life care to people experiencing homelessness with their own limited resources can feel like a Sisyphean task.

For every person given a bed, there are countless others who need and can’t access one. Each organization can only serve their local community, leaving hundreds of people or more to die on the street nationally each year.

Beyond what the organizations receive from state and local funding, there’s little — if any — government funding for long-term medical care or end-of-life care for people with no fixed address. These organizations’ funding models are largely reliant on grants and donations, without long-term stability.

“It’s local advocates who are seeing the suffering of their community members, and so they’re creating these programs that are funded by the good of people’s hearts, and that’s it,” Dobbins said.

Rocky Mountain Refuge, which opened its doors a little over a year ago, struggles to find enough funding to stay open, Hall said. That’s an experience echoed across the country.

“One of the stresses for us here is, every year, are we going to be able to keep our doors open because of the funding?” said Kowshara Thomas, director of Joseph’s House in Washington, D.C.

Founded in 1990 during the HIV/AIDS crisis, the three-story house in a quiet residential neighborhood has served community members dying of the disease for decades. This year, however, they lost a major grant that comprised 30 percent of their revenue, which worries Thomas. Other medical respites in the D.C. area receive Medicaid funding, and larger organizations are often better positioned to write grants and secure funding. But Thomas says Joseph’s House, with only eight beds, is too small to follow suit.

The organization has largely, though not entirely, pivoted from end-of-life care to medical respite, something Thomas sees as both a result of better health among their community and a way for them to provide continuing care for people after they’re discharged. Joseph’s House has around 25 community members for whom they provide supportive services.

Thomas is also proud of the community that Joseph’s House anchors, with former residents coming back for meetings, social time and sometimes additional long-term or end-of-life care.

“Having a place where you can feel safe and get the support — the medical and the psychosocial support — is really what helps our community,” Thomas said. “Joseph’s House is, for some of our residents, the first time they’ve ever had family or felt like they belonged somewhere and they could just be who they are.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!