How can social workers address difficulties in communication and help promote openness between professionals, service users, their family and other carers?

By Alice Blackwell

All social workers may occasionally need to become involved in end-of-life care, even when most of their work lies in other fields. This may arise, for example, when a service user or a member of a service user’s family has a sudden fatal accident or commits suicide, or becomes aware that they or a close relative or friend is dying.

Practitioners may sometimes worry about being pitched into end-of-life care unexpectedly because it disrupts existing plans and may lead people to express powerful emotions. As a result, the situation or emotions may seem frighteningly out of control; indeed, this is one of the fears that many people have at the end of life.

Social workers can play a key role in responding to service users’ and carers’ feelings of uncertainty and lack of control. We can also address difficulties in communication and help promote openness between professionals, service users, their family and other carers.

Communication is key

A common issue in the dying process is the extent to which service users and family members and friends are aware that they are dying; awareness develops through communication. Death and dying are often hidden in our society and are medicalised, separating them from everyday life.

Many people regard openly discussing someone’s death with them as inappropriate. This attitude may be characteristic of some people in older age groups and is also associated with the cultural expectations of some minority ethnic groups.

To help people and families with the end of life, practitioners need to be able to talk with them, and most people working in end-of-life care aim for openness. However, even if the person accepts that they are dying, some prefer not to talk about it, and their approach must be respected.

A useful approach to openness is to start from the service user’s or carer’s perspective. You can ask: “Can you bring me up to date on what you have been told by…(the doctor, nurse)?” It may also be useful to get a picture of their own assessment of their illness, and ask: “Have you noticed any changes in your condition?” Later in a serious illness, you could ask how they assess changes: “Would you say you are weaker today than last week?” To get a picture of how realistic their view is, you can ask: “What has happened that makes you think that?”

Being informed of a short prognosis often leads to a change in mood. Depression arises from focusing on the potential and actual losses, and anxiety arises from seeing the prognosis as a threat to plans for the future and relationships. Crisis theory (Golan, 1978) suggests that it may help if you can stimulate a sense of challenge, helping people to think through what they want to do with the short time they have left, reordering priorities. If you identify depression or anxiety, you could also refer the service user for medication to manage symptoms.

Completing ambitions and tasks

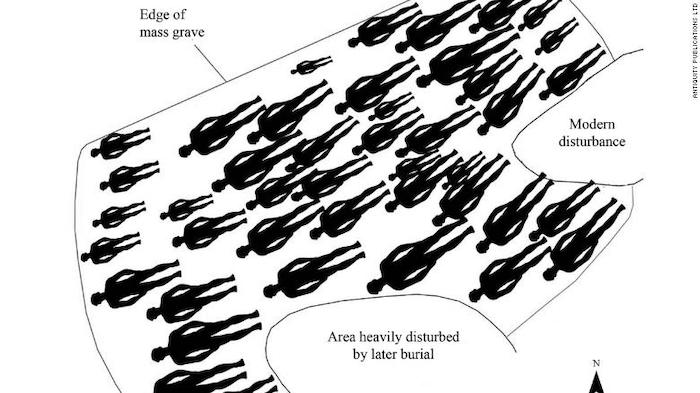

Although someone may know they are facing death soon, the end-of-life phase is often characterised by uncertainty: people do not know what is going to happen to them, or the timescale. Some people maintain hope by denial, but this may be unhelpful for them if they have tasks to complete, for example, writing a will or making care arrangements for their children after death. All hope contains a rational element, in which people look at the realities of their position, and an emotional element, in which they express aspirations or expectations.

People may wish to complete ambitions, such as swimming with dolphins, or taking a last holiday. They may wish to visit previous homes or favourite places. You can suggest possibilities to them if they have not thought of any.

Social workers can support the following aspects of emotional and psychological care:

- managing the practical and emotional consequences of increasing frailty, a progressive condition or a life-threatening illness;

- enabling dying people, their carers, families and communities to express and deal with emotional responses to the ‘bad news’ of a short prognosis and subsequent bereavement;

- helping people look forward to opportunities remaining to them in their life, and helping them to live their life within their family and within a community;

- helping people complete social and relationship ‘tasks’ (see box) and making other preparations for death;

- spiritual care (sometimes provided by a minister of religion or chaplain).

Resolving interpersonal issues

Many people wish to complete interpersonal and social tasks in the time available to them, to bring significant interpersonal attachments to a satisfactory end. These are often about resolving four important interpersonal issues:

- Saying goodbye to important people.

- Saying “thank you” for care provided and “for putting up with me”.

- Saying “I love you”, even if there has been a degree of estrangement.

- Saying sorry for some real or imagined failing, or “I forgive you” for something that has gone wrong in a relationship.

In some cases, people may have become estranged from friends or relatives who are important to them, and it can be useful to ask: “Is there anyone who you would like to know about…(your illness, admission to hospital or care home)?” and to help to approach divorced or separated parents of children who may wish or at least be willing to see the service user for a last goodbye.

Supporting family and carers

Family members and informal caregivers make a significant and irreplaceable contribution to meeting the needs of dying people. Many dying people become increasingly dependent on family, friends and other caregivers for practical and emotional help. This is particularly an emotional labour for caregivers, as round-the-clock care interacts with their own feelings of loss and other priorities in their lives.

Social workers can help by arranging practical supportive services for carers as well as offering emotional and psychological support. This might include adult day care, respite care, home care, and education and social opportunities to improve satisfaction, quality of life, and reduce the feeling of burden. Sustaining families has the secondary gain of also helping the patient.

Preparing fully for someone dying is not possible, but you may be able to help people think through how they want to let go of the relationship, particularly if there have been difficulties with it. You could talk to them about what has been important in the relationship, how they will best remember the service user and the possibility of rituals of leave-taking.

A final cuddle or sexual act may be important. If a visit to the pub is not possible, a favourite beer together may be a substitute. Information that may help people’s preparation includes: what happens to their body after death, negotiating legal requirements or what sort of funeral they want. Discussing these issues allows negotiation about individual and family preferences to take place. For others, focusing on what to do after someone has died feels inappropriate and contributes to feelings of guilt.

During the dying phase, the social worker’s role is to facilitate family members and carers to participate as they want. People often wish to be present throughout the last few hours, and hospitals and care homes usually call known relatives to the bedside; at home, carers and family members may need to be reminded to do this.

The dying person may disclose unknown relatives and friends, for example, extramarital relationships or estranged family members, and it is often a social work role to make contact. If the dying person and family agree, social workers may negotiate for them to have final contact with these relatives and friends.

It is also useful for social workers to think through their approach to providing bereavement care where a service user they are involved with is coming towards the end of life. The full guide considers different psychological and sociological models and approaches, and when they may be appropriate to use.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!