The US Supreme Court ruled in favor of same sex marriage nationwide on what would have been my 28th anniversary with my late partner. Though we were never able to marry, I still consider myself a widower.

“I am a widower.”

Those are four words I never imagined myself saying at my age. Maybe at 70 or 80. Mid-60s, if something terrible, like a plane crash or a terrorist attack, took one of us. Or never, if I was the first to go.

None of those scenarios took place.

I lost my partner, Gary Lussier, to liver disease two years ago. He was a wonderful man — a former dancer, handsome with a wicked sense of humor and a way of embracing the world that would shame most people. He didn’t get to embrace the world for long enough, though. He was 52 and I was 53 on the day I walked out of NY Presbyterian Hospital/Cornell Medical Center, dazed, confused and alone.

He died less than 24 hours before he might have had a successful liver transplant, slightly more than three days after I rushed him to the hospital, over a year since his illness began to manifest itself and about a quarter-century since we had joined our lives. Even though I was well past 50, I found myself in the “he’s too young for this to happen” category.

And, of course, there was another complication: I was not married to Gary, even though we had been together 24.5 years. Though we had no legal document, ours was as true a union as any other. Emotionally supported by our two good families and a phalanx of friends, having the benefit of treatment in New York City’s best hospital and embraced by the staff of my company, St. Martin’s Press, I had the rare luxury of being able to consider my place in the world free from legal battles and financial concerns that can be real, threatening and, occasionally, life-shattering for the one left behind.

In the days after his death I began to ask myself, “What am I now?” I was no longer “partner.” I searched and searched for a word that defined me. Finally, I settled on the most obvious and yet, for me, most problematic word: widower. In choosing it I set myself the task of understanding its meaning.

I was also trying to find the courage to say it out loud.

Of course, “widower” implies “marriage,” “husband,” “deceased wife” and — in our world — “heterosexual.” We weren’t married. We referred to each other as “partners.” I am gay. The first time I said it out loud — “I am a widower” — I was alone in my apartment. The silence was so loud it threatened to crush me.

When that sentence broke the isolation I’d been living in. I knew I had found a word that would take me forward, but one that would provoke surprise in others. “Did he say ‘widower’?” I imagined people thinking to themselves at cocktail parties. “I didn’t know they were married…” they might say, in private, when they took off their pearls or undid their ties. Worse might come from hate mongers I didn’t even know. The question obsessed me: How could I call myself “Gary’s widower” and be true about it?

For me, the ability to say “widower” came down to the question of what the word “marriage” means. We’ve all been taught “marriage” refers to the moment when two people profess vows of love before a governmental or religious authority, rings are exchanged, documents are signed and the couple runs off to Happily Ever After. They are “married.”

There is, though, a deeper meaning, I think, of the verb “to marry,” a more private one concerning itself less with ceremony and legality than with the intimacy and commitment between two people: “to take as an intimate life partner by a formal exchange of promises in the manner of a traditional marriage ceremony.” Had Gary and I done that over the years? Did we have some formal exchange of promises?

Stephen Sondheim has a song about marriage describing it as “…the little things you do together…” We certainly had our fill of them throughout the years: Not just Thanksgivings and Christmases and Easters or trips abroad or weeks on the Ogunquit beach. No, we had more than that. We had almost a quarter century of eating pizza while watching television, having dinners with friends, arguing about how best to do the laundry, having a bang-up row in public, commiserating over each other’s daily work woes and celebrating each other’s triumphs. So, in that way, we did indeed have a marriage. Through millions of small acts, private and public, we were intimate life partners.

But, did we have a “formal exchange of promises” I wondered? Over the years, every night, we said “I love you” to each other before falling asleep. Were those not exchanges of a mutual promise renewed each day? I think they were. But, were they enough to pronounce us “married”? Did we have some deeper and more formal promise? In looking back, we did, though no clergy or justice of the peace was present.

We met when a legal marriage between two men was unthinkable. We also heard the revolutionary roar of “We’ll live together unmarried!” from both straight and gay couples. Now that marriage was actually possible, I had begun to think about how wonderful it would be to have a “husband,” someone to call my own, someone defined by a word that could not be mistaken for a business associate: “husband,” not “partner.” Just thinking of those words made me feel different: stronger, safer and — in a corny way — a man-in-love.

When the New York State gay marriage law was finally passed in 2011, we were at our house in Massachusetts where gay marriage was already legal. It was a beautiful day and we were in the garden, weeding. Gary seemed to be on the mend after his initial diagnosis and treatment. I had felt a strong “are we going to get married?” vibe from him since we heard the news. There in the garden, down on one knee as I was weeding around the boxwoods, I said, “Gary, will you marry me?” He was shocked. So was I. He said, in a typically Gary way, “Well, I don’t see a ring…” And, then, to my surprise, he said “No … not until you get me a ring …” as much with shock that I had asked as he was by the need to answer. I was crushed. I had never asked anyone to marry me before, but there it was. “No.”

Not long after that day, Gary began to spiral downward again and the incident was pushed aside by multiple hospital stays, the imperfect weekly calculation of his place on the liver transplant list, the day-to-day monitoring of weight, at-home visits from medical workers, frantic expeditions to specialty pharmacies and, most wrenchingly, the ups-and-downs of watching the person you love most in the world become increasingly and dangerously ill.

My marriage proposal remained buried in our garden until about an hour before Gary began to die. He was in the ICU, his liver failing (unbeknownst to me). He was drifting in and out of consciousness. During one lucid moment, he grabbed my hand, pulled me to him, eyes wide-open staring straight into mine, and said, “I do!” with such vehemence that it startled me.

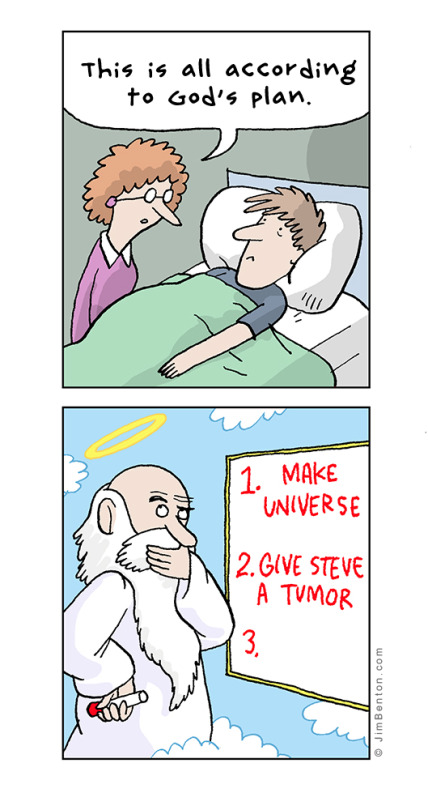

I was speechless; but, since I was his chief cheerleader on the road to transplant, I said “Oh, no you don’t… we’ll do this right once you get your liver …” He laughed a little. If God or The Idea of God has to do with love, I like to think that He or She was present when that vow was made because, if true love has ever made itself manifest, it was in that moment. We finally had our formal ceremony and I clasped his hands tightly. An hour later, the massive hemorrhage that ended his life began and he lost all consciousness. Months later, I told a friend that I wished I’d said “I do, too!” and he said, “You did, on that day in your garden.”

I now understand that we were, indeed, married in so many ways that I have come to say, “I am a widower” with confidence, if with little joy. It’s not a nice thing to have to say. It puts people off, or — even worse — makes them want to take care of you when you least need it. That statement’s message is “I lost my spouse, but I am still alive. I’m standing on my own two feet and intend to go on living for as long as I can.” It means you freely have given a significant part of your life to someone who is now gone and that you are alone. It means, “I remain while he has moved on.” It also now, thankfully, has less relationship to gender preference. As Wendy Wasserstein wrote: “Love is love. Gender is just spare parts.”

How, then, do you say, “I am a widower”? It has nothing to do with age. Young or old, you say it plainly, like saying “armor,” knowing that nothing else can ever hurt you as much as your spouse’s death. You say it in the full knowledge that the union you had with your deceased spouse was as deep and as rich and as true as any other. You say it with remembrance and, most of all, you say it with love and pride for the spouse who has passed on — that singular, unforgettable human being who taught you, truly, how to love and to be loved.

“I am a widower.”

Complete Article HERE!