When a hospice counselor is called to the bedside of a child who has just died, he leads the parents through a Buddhist ritual for cleaning the body. In the process, he guides them through the fires of grief, which burn away everything but love.

One day, in the middle of writing a foundation grant report, I got a call from a man I didn’t know. He explained that he was the father of a 7-year-old boy who had been very ill with cancer. Some people had told him that I might be able to help him out.

I said certainly, I would be willing to help the family through their grieving process. I made some suggestions about how I might be able to support when the time was right.

The man paused. It was clear that I didn’t understand yet what was happening. He practically whispered, “No, Jamie died a half hour ago. We’d like to keep our boy at home in his bed for a little while. Can you come over now?”

Suddenly, the situation wasn’t hypothetical; it was real and staring me in the face. I had never done anything like this before. Sure, I had sat at the bedsides of people who were dying, but I had not attended the death of a young child with two grieving parents in unimaginable pain. I honestly had no idea what to do, so I let my fear and confusion arise. How could I possibly know in advance what was needed?

I arrived at the house a short while later, where the dispirited parents greeted me. They showed me to the boy’s room. Walking in, I followed my natural inclination: I went over to Jamie’s bed, leaned down, and kissed him on the forehead to say hello. The parents broke into tears, because while they had cared for him with great love and attention, nobody had touched the boy since he had died. It wasn’t their fear of his corpse that kept them away; it was their fear of the grief that touching him might unleash.

I suggested that the parents begin washing the boy’s body— something we often did at Zen Hospice Project. Bathing the dead is an ancient ritual that crosses cultures and religions. Humans have been doing it for millennia. It demonstrates our respect for those who have passed, and it is an act that helps loved ones come to terms with the reality of their loss. I felt my role in this ritual was simple: to act with minimal interference and to bear witness.

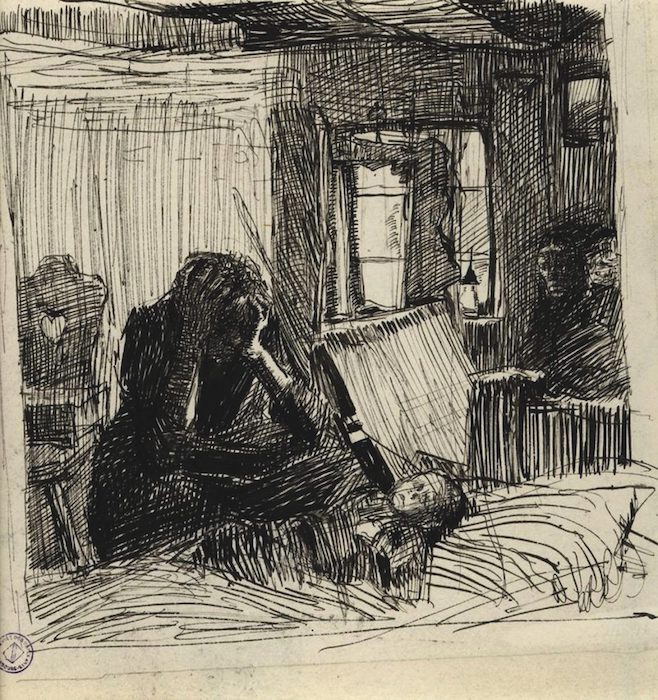

The parents gathered sage, rosemary, lavender, and sweet rose petals from their garden. They moved very slowly as they put the herbs in warm water, then collected towels and washcloths. After a few moments of silence, the mother and father began to wash their little boy. They started at the back of Jamie’s head and then moved down his back. Sometimes they would stop and tell one another a story about their son. At other times, it all became too much for the father. He would go stare out the window to gather himself. The grief filling the room felt enormous, like an entire ocean crashing upon a single shore.

The mother examined and lovingly cared for each little scratch or bruise on her son’s body. When she got to Jamie’s toes, she counted them, as she had done on the day he was born. It was both gut-wrenching and extraordinarily beautiful to watch.

From time to time, she would look over at me as I sat quietly in the corner of the room, a beseeching question filling her eyes: “Will I be able to survive? Can I do this? Can any mother live through such loss?” I would nod in encouragement for her to continue at her own pace and hand her another washcloth, trusting the process. I felt confident that she would find healing by allowing herself to be in the midst of her suffering.

It took hours for the parents to wash their son. When the mother finally got to the face of her child, which she had saved for last, she embraced him with incredible tenderness, her eyes pure reflections of her love and sorrow. She had not only turned toward her suffering; she had entered into it completely. As she did, the fierce fire of her love began to melt the contraction of fear around her heart. It was such an intimate moment. There was no separation between mother and child. Perhaps it was like his birth, when they had the experience of being psychologically one.

After the bathing ritual was complete, the parents dressed Jamie in his favorite Mickey Mouse pajamas. His brothers and sister came into the room, making a mobile out of the model planes and other flying objects he had collected, and they hung it over his bed.

Each one of them had faced unbelievable pain. There was no more pretense or denial. They had been able to find some healing in each other’s care and perhaps in opening to the essential truth that death is an integral, natural part of life.

Can you imagine yourself living through what these parents did? “No,” many of you will say, “I cannot.” Losing a child is most people’s worst nightmare. I couldn’t endure it. I couldn’t bear it, you may think. But the hard truth is, terrible things happen in life that we can’t control, and somehow we do bear them. We bear witness to them. When we do so with the fullness of our bodies, minds, and hearts, often a loving action emerges.

And sometimes they act with enormous compassion toward others who have suffered similarly or who may yet in times to come.

One of the most stunning images of this that I can recall came after the major earthquake and tsunami disabled the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan. A photo in the newspaper revealed a dozen elderly Japanese men gathered humbly, lunch baskets in hand, standing in a line outside the plant’s gates. The reporter explained that they were offering to take the place of younger workers inside who were attempting to contain the radiation-contaminated plant. In total, more than five hundred seniors volunteered.

One of the group’s organizers said, “My generation, the old generation, promoted the nuclear plants. If we don’t take responsibility, who will? When we were younger, we never thought of death. But death becomes familiar as we get older. We have a feeling that death is waiting for us. This doesn’t mean I want to die. But we become less afraid of death as we get older.”

Suffering is our common ground. Trying to evade suffering by pretending that things are solid and permanent may give us a temporary sense of control. But this is a painful illusion, because life’s conditions are fleeting and impermanent.

We can make a different choice. We can interrupt our habits of resistance that harden us and leave us resentful and afraid. We can soften around our aversion.

We can see the way things actually are and act accordingly, with wise discernment and love.

The Thai meditation master Ajahn Chah once motioned to a glass at his side. “Do you see this glass?” he asked. “I love this glass. It holds the water admirably. When the sun shines on it, it reflects the light beautifully. When I tap it, it has a lovely ring. Yet for me, this glass is already broken. When the wind knocks it over or my elbow knocks it off the shelf and it falls to the ground and shatters, I say, ‘Of course.’ But when I understand that this glass is already broken, every minute with it is precious.”

After being with Jamie’s parents as they bathed their son, I returned home, and I held my own child very close. Gabe was also 7 years old at the time. I saw clearly how precious he is to me, what a joy he is to have in my life. While I felt devastated by what I had witnessed, I also was able to appreciate the beauty in it.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!