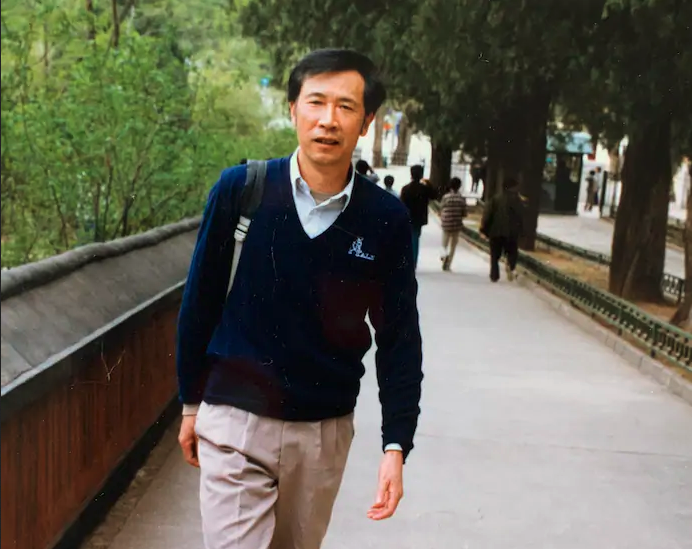

It brought me back to my father’s deathbed in China.

By Xiaoyan Huang

I thought for sure he was dead: Whenever I cannot reach my father, now 86, I am convinced the day has come and that he has died alone in his apartment. It was nearly midnight in Shenzhen, China. I tried calling him on WeChat, on his cell, on his landline. No answer. I called his friend to check on him. He answered the doorbell that night and seemed okay, she reported. The picture she sent, though he was smiling, did not reassure me. I’m a cardiologist in Portland, Ore. One look at my father’s ashen color told me his end was near. A week later, he was hospitalized and diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer.

This event had a cruel symmetry, echoing what happened in 2003 when my mother suffered a fall and massive brain bleed. Same apartment. Same hospital. Even the pandemics, then and now, involve related viruses: SARS and the novel coronavirus. My mother had gone into a coma by the time I reached her bedside. After months of hospitalization, she was discharged home, comatose. My father kept her alive in a persistent vegetative state for five more years, with hired help and tube feeds, nearly bankrupting himself. Throughout that time and long after, I was overtaken by guilt. Thirty-four years ago, my parents supported their only child to pursue her education in the United States. It pained me to realize that as a physician, I was unable to save my mother’s life, and as a U.S. citizen, I never gave her the good American life she had asked of me.

This time, I was determined to do right by my father. Though I managed to leverage my connections as an established American cardiologist to get him VIP treatment in his local hospital, he adamantly declined further diagnostic testing or care. My father, a retired university professor, is fiercely independent, a loner. He told me he had lived a long, good life and wanted to die on his own terms. When I gently suggested getting a colonoscopy, tissue biopsy and perhaps advanced cancer therapy, he got mad: “I am fine, I can walk to the crematorium myself!”

Palliative and hospice care are not widely supported in China. When loved ones fall ill, spouses and children often show over-the-top devotion, fearing judgment by other family members and by society at large. In cases of terminal illness, the patients themselves almost never participate in discussions about the severity of the condition (a situation depicted in the 2019 film “The Farewell”). Family members are expected to pursue more aggressive treatment, even if medically futile, espousing blind optimism. The higher the price tag, the better the demonstration of filial piety. Dying at home is generally avoided because of superstition. In China, my father faced intimidating cultural stigma against his wish to stop treatment and die peacefully at home.

I wanted to support him, but it would mean figuring out his end-of-life care on my own. After consulting an oncologist friend, I packed my suitcase full of over-the-counter comfort care medicines. I also had to make arrangements to put my life on indefinite hold — applying for family medical leave, rescheduling appointments, asking colleagues to cover my patients and administrative duties, saying goodbye to my husband and children with no set return date.

Decades ago, I was fortunate enough to attend college in America on a full scholarship. Now it would take every inch of my immigrant success — leaning on all my resources and institutional affiliations — to take the return trip on which I would probably lose my remaining parent and sever my last tie with China. Travel during the pandemic is dauntingly difficult: I needed a special family emergency visa, two negative coronavirus tests within 48 hours of my flight and a time-stamped health clearance bar code from the Chinese Consulate. There were only a handful of flights between the countries each day; it was impossible to buy tickets online. With the help of a childhood friend’s wife, who runs a travel agency in China, I got one. The plane was packed. Everyone wore N95 masks, some with double masks, others with goggles, face shields, hazmat suits and gloves. The flight attendants wore disposable surgical gowns. People hardly ate or drank during the 15-hour flight, trying to minimize bathroom trips.

For two weeks, I was quarantined in a hotel room in Xiamen after landing. The first night, on a sleepless high, I made grandiose plans for catching up on emails and work. By day five, I started exercising by putting all 20 hotel-provided bottles of water into a backpack and pacing the room: 14 steps long, six steps wide, over and over. By day seven, each banging of the door by the hotel staff, announcing meals delivered to a chair outside, made me jump — as did the twice-daily temperature check. Finally, after 14 days and 11 negative coronavirus tests, I was released into the world.

When I finally got to my father’s bedside, suitcase in tow, it was almost anticlimactic. For a surreal second, I felt I was rounding on an elderly patient, as I do every day in my hospital. Reunion in Chinese style, even in such weighted circumstances, is restrained. No matter how many times I had cried in private, there would be no embrace, not even a handshake, no tears in front of him. I instinctively checked on key physical exam findings: Was his neck vein elevated, and legs swollen, suggesting congestive heart failure? I stopped myself just short of probing his abdomen. My hand went, instead, to tuck him into his comforter. At this moment and going forward, I wanted to be only his daughter.

A few days later, I brought my father home. Together with a friend of his, I took care of him: shopping for and cooking his favorite meals; helping him shower and dress; dispensing his few remaining pills. Back in his own environment, my father instantly began feeling better, eating more. We still don’t use the word “cancer” or talk openly about his prognosis, but this feels like neither denial nor forced optimism. Instead, we focus on the concrete tasks at hand. When he has energy, I sit by his bed listening to him talk about his life, about history, philosophy and technology. I tell him about his grandsons and their girlfriends, my work and my life.

I began this journey initially stricken by grief, and by fear of reliving the guilt my mother’s death had induced. But I came to appreciate an unexpected symmetry: Years ago, my parents sacrificed to set me free and allow me to pursue a new life in America. In returning to China, I sacrificed to set my father free and help him have a good death. The first choice is relatively common and often celebrated; the latter is unconventional, even frowned upon — seen as almost unnatural in a culture that prioritizes extending life. But the limbo of quarantine, and all the hurdles I had to surmount en route, brought me to a realization: how important it is, for the living and the dying, to share a moment of peace. In that moment, love is no longer measured by the quantity of pills, the number of CT scans or the extent of heroic medical interventions, but by time spent together.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!