Jaimal Yogis’s dad explained his final wishes: “I’ve gotten so much from Buddhism for good living, I’m not going to pass up their tips for good dying.”

by Jaimal Yogis

The first and only time I bought dry ice, the grocery store clerk asked if I was going camping. “No,” I muttered, then managed to stop myself from saying it was for a body. The ice really was to lay my father’s corpse on.

An air force colonel who was skeptical of organized religion, my father, who we call Pa, wasn’t sure the Tibetan Buddhist tradition of leaving the dead undisturbed for three days was necessary. But, as he said after being diagnosed with late stage lung cancer, “I’ve gotten so much from Buddhism for good living, I’m not going to pass up their tips for good dying.”

As if summarizing Socrates in his famous pre-execution speech, Pa often said he had no idea where he was going. ‘If the lights go out, it’ll be a good rest,’ he’d say. ‘And if there’s more, it’ll be a great adventure.’

These three days are not unique to Tibetan, or more accurately, Vajrayana Buddhism. Irish wakes often last two or three days while a soul departs, and Jewish Midrashic texts say a soul hovers over the body for three days (or seven) until the body is buried. The idea behind the three days in Vajrayana Buddhism is that as the breath and heart stop, our gross level of consciousness dissolves but more subtle levels of consciousness remain in the body for up to about seventy-two hours. During that time the subtlest stream of consciousness is said to leave, a transition known to go more smoothly if the body can chill—in Pa’s case literally since under California law dead bodies have to be kept on ice.

“Otherwise they tend to smell like dead bodies,” our hospice nurse informed us.

“Right,” I nodded. “And where do we get the ice?”

“Grocery store.”

“Of course.”

As if summarizing Socrates in his famous pre-execution speech, Pa often said he had no idea where he was going. “If the lights go out, it’ll be a good rest,” he’d say. “And if there’s more, it’ll be a great adventure.” Still, he’d reasoned his way toward the three-day death plan. In addition to reading up on how Vajrayana Buddhists use strict tests to prove they’ve found reincarnations of former teachers, he’d read the work of doctors like Sam Parnia of NYU Langone Health. Dr. Parnia has meticulously catalogued data on people who’ve died clinically, sometimes for hours, before being resuscitated. These briefly dead folks often report vivid dreams after waking, sometimes ones in which they correctly recount what doctors had been saying—“Going to the game later?”—when the patients had no heartbeat. “That’s enough evidence for me,” Pa said. “Don’t poke or prod me for a few days.”

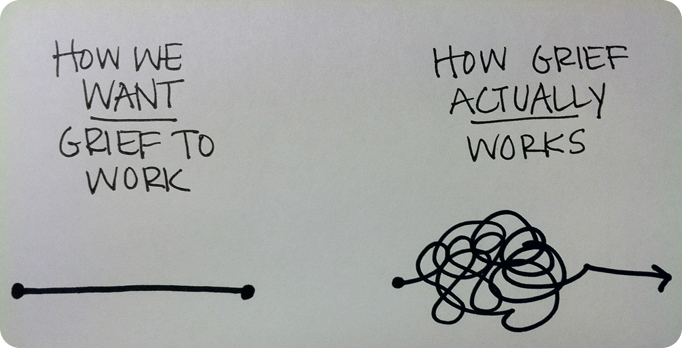

As the actual death part of the three-day death plan approached, we—his family—wondered if having Pa’s cold body steaming on carbon dioxide in the bedroom might intensify our grief. And might it be a little creepy? It turned out to be just the opposite.

Death leaves you in a dreamy shock. You don’t know if you should wail or drive all night to Mexico or finally get to writing your own will. When Pa stopped breathing on a warm summer evening, dressing him in his aloha shirt and favorite Christmas socks, then adorning his room with flowers, was just the beautiful busy work our reeling minds needed. Reading Jane Hirshfield’s “It Was Like This: You Were Happy,” a special request from Pa, while he was actually there in the room felt more heart opening than reading it again while scattering his ashes. And as we sat with Pa each of the three mornings while reading him The Tibetan Book of The Dead—a text meant to help us navigate the space between lives—it felt as if we were on a kind of spiritual tour bus with him, visiting the realms where awakened beings are born from lotuses and truths are whispered on the breeze.

Perhaps most surprising was how much the three-day death plan helped before death. As Pa was starting to show signs of getting close to the end, my sister Ciel and I asked if he would like to hear a Medicine Buddha ceremony that is often done for the sick and dying. “You don’t have to bother with that,” Pa said, continuing his usual stubborn quest to keep us from doting. But we argued that the ceremony would be a good warm-up for when he was down for the count and we were reading The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which Tibetans actually call The Great Liberation for Hearing in the Bardo. Since this made it sound like the reading was for us, Pa agreed.

We sat around his bed, switching back and forth between botching the Tibetan chanting and reading the English translation. The ceremony took about an hour, and we thought Pa had slept through it. But at the end, he sat up with tears in his eyes. “I am so honored you did that for me,” he said. “And now I’m going to get up and see the sky one more time.”

“We’ll get the wheelchair,” Pa’s wife, Margaret, said reasonably.

“No,” he said, “I’m going to walk.”

Pa had already fallen behind the toilet in such a precarious position we’d needed the fire department to come dislodge him, and he’d been bedridden for days now. But charged up by the chanting, Pa managed to lumber slowly to the back porch, rasping with every breath.

We opened the door. Pa turned his face up bracingly to the blue. He looked so pale, I half expected him to croak right there. Instead, he then looked down at a few small stairs he would have to navigate in order to be fully outside. “Take me back,” he whispered. “I want an easy death. Not to fall off the damn steps.”

We laughed. Finding humor in the face of hardship was one of Pa’s great gifts. But we hadn’t heard zingers with gusto like this for a few weeks. And I think, in addition to the power of the ceremony itself, knowing that his family would be there for three full days—botching more Tibetan chants around him—was a great comfort, a lightening.

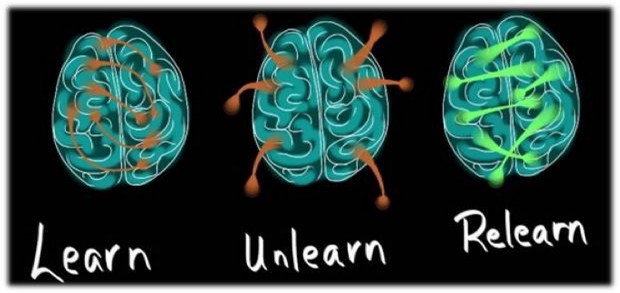

Philosophical aspects of the plan were helpful too. In hospice Pa occasionally felt unsure of where—even who—he was. One day he called himself King Henry and my aunt the queen. “You wouldn’t believe what’s happening,” he told me. “It’s like I’m disappearing.” This was scary, but Buddhist wisdom for conscious dying gave Pa a place to put his fears.

According to Vajrayana Buddhists, our gross consciousness is where we construct our version of reality through our senses. This construction is like a video game in our heads in which we are the most important character, the one whose suffering matters most, the one who should win all the gold coins because, as our senses (falsely) tell us, we exist separately from the rest of reality. The more we let go of this illusory separation from others, the more room there is to experience our true blissful and compassionate nature. Vajrayana Buddhist teachers say this true nature is most easily accessible at death because, as opposed to meditative glimpses beyond the veil, in death the gross levels of consciousness drop away automatically. So, when Pa was scared or disoriented, we could remind him that losing a mere idea of himself was not just natural, it was part of spiritual awakening.

In his last hours, Pa’s brow was furrowed and his body appeared tense. He looked like he was trying desperately to remember something. Ciel, Margaret, and I were taking turns sitting with him, and fittingly it was just when Margaret was singing him Nat King Cole’s, “When I Fall in Love,” a song they’d danced to on West Cliff Drive above the sea, that Pa finally let go. As he did, his brow smoothed completely, making him look instantly younger. A distinct half-smile appeared on his lips. A Buddha smile. And whether it was Pa’s newfound bliss, rigor mortis, or some combination of both, that smile remained perfectly serene for all three days.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!