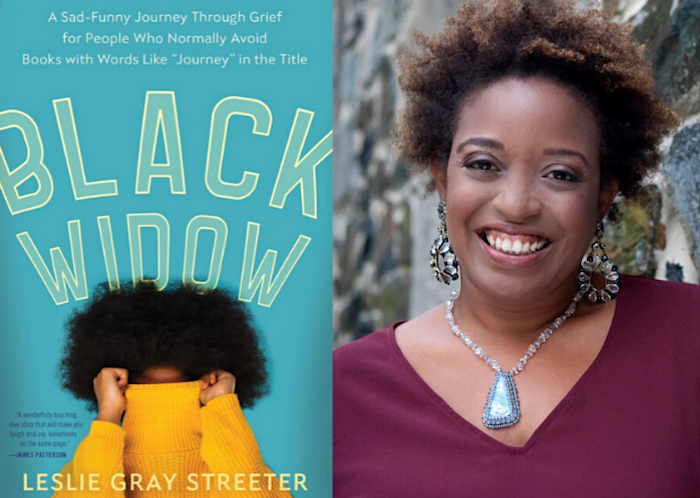

And A Conversation About Finding Humor In The Grieving Process

Leslie Gray Streeter is no stranger to grief. The former Palm Beach Post columnist lost her husband Scott five years ago to a sudden cardiac arrest.

She details the struggle of overcoming that grief while fighting to adopt her son Brooks, all with a sense of humor in her new memoir “Black Widow: A Sad-Funny Journey Through Grief for People Who Normally Avoid Books with Words Like Journey in the Title.”

“You’ll forgive me for not thinking clearly right now because my husband very recently dropped dead in front of me while we were making out. And when I say very recently. I mean yesterday. I have to pull myself together and deal with this sometime. Well, right now, probably what I really want to do is jump on the golf cart from which my mother is nervously watching me and drive us to the nearest bar,” she writes in her book.

WLRN’s Luis Hernandez spoke with Streeter about her new book and finding humor in the grieving process.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

WLRN: You wrote this book a short time after your husband’s death. Were you finding humor in these moments as they were happening? Or were you trying to find the humor on purpose?

STREETER: I think that you’ll agree with me probably that the worst humor is [from] the ones that are there trying to be on target. When people go, “I’m going to try to be funny,” that’s usually strained and it’s labored and it’s too on the nose. I just started writing and I would go back over the sentence or the paragraph for the page and say, “was there anything funny in there?” And there usually was, because that’s just sort of the way it came. I spent a lot of time reviewing books and reading books, particularly celebrity autobiographies and memoirs. And the most irritated I ever was, was when people were holding back. The people whose books are the most fun were usually people who’d been in show business for 30 or 40 years, gone to rehab, had some bad marriages, been in and out of a cult—because they don’t care anymore.

You’re a Christian and your husband was Jewish. What role did your faiths play in your relationship?

There are some people who at whatever part of their life decide that their faith is either non-existent, it’s merely cultural or it’s something they’re still hewing to. Both of us could probably say that the faith we had at that moment was not exactly the same as when we grew up. We still both believed in God and we still both believed in a similar moral compass and moral code. We made sense of each other. He would say, “I believe in the in the original and you believe in the sequel.”

You had made the joke that if he died on you, you would pick the outfit for him to be buried in. What did he wear for the funeral?

We buried him in a Brooks Robinson jersey because my son’s name is Brooks Robinson. And he would want to be buried with something of Brooks. I know it. And that was a very, you know, special thing for him. Then a pair of dress pants, because I was not going to bury him in sweats or raven shorts, and then his raven sandals. I wanted to make it somewhat classy. And I’m sure there was some conversation back and forth when they were dressing him. But no one said anything to me about the outfit. It wasn’t an open casket anyway. There he was, he looked like himself.

What significance do you hope this book is going to have for your son, Brooks when he’s old enough to read it?

I hope that he can read it, particularly parts about Scott and about who he was, because it’s so unfair that he died when Brooks was 2-years-old. That to me is so unfair. God and I are still not cool with each other about that. But I want him to know not only how wanted he was in our entire family, but to Scott. He would have done anything for this child and being this child’s father meant everything to him. And I want him to know that Scott was also not some saint. He was a goofball. We got into fights about raven shorts and stupid crap. He was a human being. I want him to be a living, breathing person. And I hope that this book does that to him. Also, maybe in the moments when he’s a teenager and he thinks I’m insane he can read this and say, “okay, she did do some stuff. She’s not just the person who’s trying to thwart my happiness.”

Have you gotten any response from people about how this book has helped them on their own grieving journey especially during this time of a pandemic?

In this pandemic, grieving is twofold. It’s both grieving people who physically died and people who just happened to die of anything else during this time. So the way that you were able to mourn them was not the way it used to be. Now it’s Zoom funerals and memorials and that kind of thing, rather than being in person. It’s never going to be like it was. People have said to me that my book has been helpful not only because it’s about grief but because, without trying to, I just wrote a book that was about having to do it and saying my life changed. I still have to pay the mortgage and the bills. My life changed. And I still had to keep moving. There’s no one right way to do this. You cannot fail the process of mourning. Those who lost people during a pandemic and those who are just beginning to grieve or whose grieving came full circle during this time told me, “thank you just for like saying you get to be messy with grief.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!