How Can Couples Stay Connected & Grieve Together?

October is special for a lot of reasons and one of which is Pregnancy and Infant Loss month (PAIL). PAIL is a true trauma that test lovers’ will, relationship, and self-preservation. This month, I brought in an expert, Jeanae M. Hopgood, MFT, M.Ed, PMH-C (@black_angel_mom) to help educate about PAIL, talk to us about resources and how to preserve a relationship when PAIL hits close to home.

Dr. Lexx: Who are you and what are your credentials?

Hopgood: I am an individual, couple/partner, and family therapist specializing in sexuality & sexual identity, perinatal mental health, perinatal loss, family creation, and family of origin challenges. I am also a mother of three (one earth-side, and twin daughters who passed), an author, owner & CEO of JHJ Therapy, LLC, and creator of the Black Angel Mom brand (virtual community, support groups, journal and blog).

Dr. Lexx: What is PAIL and how do we use October to honor it?

Hopgood: PAIL is an acronym for Pregnancy and Infant Loss. October is PAIL Awareness month and involves several global, as well as local events. PAIL Awareness Day and the Wave of Light occur on October 15th yearly. Some people also use the opportunity to have small gatherings to honor their children that have passed; particularly when there are unclear birth or death dates. Others may choose to use the time to address their loss(es) in private during this time of year, with candles, or journaling, or looking through memorabilia.

Dr. Lexx: How did you come to have a passion for this work?

Hopgood: I have always had an interest in perinatal health and mental health, as well as family creation; however, my specific focus on perinatal loss came out of my own experience with the phenomenon. On June 7, 2017, I gave birth to my twin daughters, Aviva Monroe and Jora Nirali, at just shy of 17 weeks (16w 7d) gestation due to Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes (pPROM).

My daughters were born alive just after 9pm that evening and died shortly after. Them dying was the biggest, darkest, deepest state of grief I have ever experienced. I was already working as a therapist and had some awareness and skill with coping; however, nothing could have prepared me for the depths of pain I would feel. Writing became [such] an outlet for me that I also decided to create a blog. So, the Black Angel Mom blog was birthed.

Dr. Lexx: What are some of your favorite tools to help with grief?

Hopgood: There are many ways one can approach the work but one of my favorites is just telling your story. Particularly in the case of perinatal loss. For folx with this experience, this is literally the only story they will have about their lost loved one (llo). It’s the only memory(ies) of their llo, so it is crucial for them to be able to tell that story.

In terms of actual, tangible tools, my journal is my fav! The Black Angel Mom Guided Journal is chock full of exercises and activities to help identify specific parts of the grieving process, set boundaries for oneself to help create emotional safety with partners, family, and friends. It also has a ton of free-writing space, processing space after activities, and coloring pages that folx can find relaxing. The journal is good for individual use, as well as use with a support professional (i.e., a therapist). I will also soon be releasing a card deck full of conversation starters and processing prompts for personal use, and/or use with your therapist or support group, and partners. Subscribe for the release or join the Facebook Group to connect!

Dr. Lexx: With loss of a wanted child, there is often a rift between lovers. What tips do you have to help people reconnect to their intimacy?

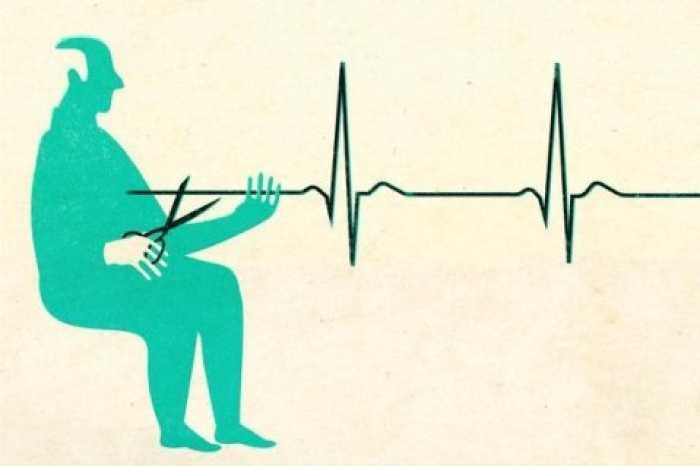

Hopgood: The loss of a child is traumatic, regardless of the gestational age. It feels unnatural for children to die before they have ever really lived any life. The brain literally struggles to compute this information. It tries to make sense of the nonsensical because it’s super distressing to not understand something. This is the case with perinatal loss too.

Lovers/Partners/Couples are both individually and collectively trying to understand WHY their pregnancy ended or their baby died. It’s not uncommon for the pregnant person to blame themselves and/or for their partner to blame them.

1. Blame can too often lead to shame & guilt, which are both intimacy-killers.

Intimacy — as in feelings of emotional closeness, safety, security, vulnerability — can be heavily damaged during periods following perinatal loss. It is not uncommon for partners to stop talking to each other about their feelings. Sometimes this is because they do not know what to say, sometimes one partner doesn’t want to trigger the other partner, sometimes one partner appears to be managing “well” so the perception is that they aren’t grieving “enough.”

I think one of the most important tips is to remember that everyone’s grief looks different. There are no grief olympics. When partners stop comparing their grief experiences, they are more inclined to seek understanding and empathy. Another tip is to keep talking to each other! Grief is hard and sometimes it makes you want to turn inward: away from the world and away from connection. Though alone-time is sometimes needed, it can also be dangerous to intimacy. Intimacy is about connection, not disconnection. Don’t stop talking to each other and don’t stop asking questions.

3. Seek support.

Find that support group. Find that therapist who specializes in grief work and/or perinatal loss, and also in sex therapy when possible. Support groups can provide a sense of solidarity and understanding, while therapy helps with actual interventions and deep unpacking of issues affecting relational health.

4. Grace is required.

My fourth tip is to be gentle with your bodies and do things that bring it pleasure. After perinatal loss, the relationship to one’s body can be more complex than ever. Depending on the circumstances, the body may have also recently experienced immense pain and discomfort. Healing is required.

Doing things that simply make your body feel good (e.g. dancing, yoga, sexual acts depending on clearance from a doc, exercise, massages, acupuncture, etc.) can help to nurture and change the relationship to the body making physical and sexual intimacy more desirable.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!