— Should doctors say no?

Studies show that when cancer returns, patients are often quite willing to receive toxic treatments that offer minimal potential benefit.

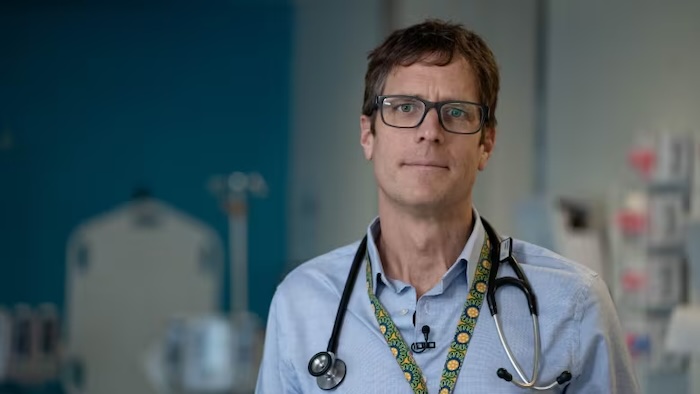

By by Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD

My patient was in his early 30s and his leukemia had returned again following yet another round of treatment.

He was a poster child for the recently reported rise in cancer rates in the young, and had just asked me what chemotherapy cocktail I could devise for him next, to try to rid him of his cancer.

I hesitated before answering. Oncologists are notorious for always being willing to recommend to our patients one more course of treatment, even when the chances of success are negligible.

One grim joke even poses the question, “Why are coffins nailed shut?” The answer: “To keep oncologists from giving another round of chemotherapy.”

This unflattering stereotype is unfortunately backed by data. In one analysis of patients with a cancer diagnosis treated at one of 280 cancer clinics in the United States between 2011 and 2020, 39 percent received cancer therapy within 30 days of death, and 17 percent within two weeks of dying, with no decrease in those rates from 2015 to 2019.

My patient had received his leukemia diagnosis five years earlier, and initially, following chemotherapy, his cancer had entered a remission. He and his parents were farmers from Latin America and relocated at the time to the United States to focus on his treatment. When the leukemia returned after a year, he underwent a bone-marrow transplant, and that seemed to do the trick, at least for a while.

But then it reared its ugly head a couple of years later, and we worked to slay it with yet more chemotherapy and another transplant.

That victory was short-lived, though, and multiple rounds of unsuccessful treatment later, here we were. The last course had decimated his blood counts, landing him in the hospital with an infection, a bad one that he had barely survived.

Does it help patients live longer or better?

Giving chemotherapy toward the end of life would be justifiable if we benefited our patients by enabling them to live longer, or live better. While that’s our hope, it often isn’t the case.

Other studies have shown that patients with cancer who receive treatment at the end of life are more likely to be admitted to the hospital and even the intensive care unit, less likely to have meaningful goals-of-care discussions with their health-care team, and have worse quality and duration of life.

Recognizing this, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has identified giving chemotherapy within two weeks of death as a poor-quality indicator that may adversely affect payments to hospitals. As a consequence, cancer doctors are discouraged from offering treatment to patients at the end of life, and can get in trouble with hospital administrators for doing so.

Despite the CMS measure, though, over the past three years the percentage of patients treated at the end of life hasn’t changed much, with one recent study actually showing an increase in patients treated.

Why do we do it? Perhaps optimism is part of our nature, and what draws us to a career in oncology. I focus on the positive, and that may actually help my patients. Other studies have shown that optimism in people with cancer is associated with better quality of life, and even longer survival.

And perhaps the data on giving chemotherapy close to a person’s last days on Earth, and the CMS quality metric, are unfair, and insensitive to the realities of how doctors and patients make decisions.

I stared back into the eyes of my young patient and then into those of his father, who was about my age. He looked kindly, with a thick, bushy white mustache, a red tattersall shirt, and work jeans. This man adored his son, accompanying him to every appointment, and always warmly clasped my right hand with both of his in thanks for our medical care — a gesture I felt unworthy to receive, given my inability to eradicate his son’s leukemia.

If our roles were reversed, how would I react if my son’s cancer doctor told me that the option for more chemotherapy was off the table, as CMS recommends, given the less than 10 percent chance that it would work, and the much higher likelihood that it could harm?

Wouldn’t I demand that the doctor pursue any and all means necessary to save my son’s life? Patients often do, and studies have shown that patients with cancer that has returned are quite willing to receive toxic cancer treatments that promise minimal potential benefit.

We discussed giving another round of chemotherapy, though I told my patient and his family that I was reluctant to administer it given the vanishingly slim chance that it would help. We also talked about my patient enrolling in a clinical trial of an experimental drug. And finally, we talked about palliative care and hospice, my preferred path forward.

“You’ve given us a lot to think about,” my patient told me as he and his family got up to leave, even smiling a bit at the understatement. His father came over to me and clasped my hand warmly, as usual.

But a couple of days later, despite how well he looked in clinic, my patient developed an infection that landed him in the intensive care unit. If I had given him chemotherapy, we would have blamed the treatment for the hospitalization.

But the cause actually lay with his underlying cancer, which had compromised his immune system, making him more vulnerable to infections. This time, my patient became sick enough that he decided enough was enough, and he accepted palliative care.

For many of my patients at the end of life who doggedly pursue that “one more round” of chemotherapy, a hospitalization becomes the sentinel event convincing them that the side effects of treatment just aren’t worth it anymore. It’s then no wonder people die so soon after their final treatment and time in the hospital.

It isn’t justifiable to give people with cancer chemotherapy when it is futile, just to be able to say “we tried something.” That’s what the CMS quality metric is trying to prevent. But in doing so, it shouldn’t interfere with a patient’s opportunity to come to that decision themselves.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!