By Lindsay Ryan

He has an easy smile, blue eyes and a life-threatening bone infection in one arm. Grateful for treatment, he jokes with the medical intern each morning. A friend, a fellow doctor, is supervising the man’s care. We both work as internists at a public hospital in the medical safety net, a loose term for institutions that disproportionately serve patients on Medicaid or without insurance. You could describe the safety net in another way, too, as a place that holds up a mirror to our nation.

What is reflected can be difficult to face. It’s this: After learning that antibiotics aren’t eradicating his infection and amputation is the only chance for cure, the man withdraws, says barely a word to the intern. When she asks what he’s thinking, his reply is so tentative that she has to prompt him to repeat himself. Now with a clear voice, he tells her that if his arm must be amputated, he doesn’t want to live. She doesn’t understand what it’s like to survive on the streets, he continues. With a disability, he’ll be a target — robbed, assaulted. He’d rather die, unless, he says later, someone can find him a permanent apartment. In that case, he’ll proceed with the amputation.

The psychiatrists evaluate him. He’s not suicidal. His reasoning is logical. The social workers search for rooms, but in San Francisco far more people need long-term rehousing than the available units can accommodate. That the medical care the patient is receiving exceeds the cost of a year’s rent makes no practical difference. Eventually, the palliative care doctors see him. He transitions to hospice and dies.

A death certificate would say he died of sepsis from a bone infection, but my friend and I have a term for the illness that killed him: end-stage poverty. We needed to coin a phrase because so many of our patients die of the same thing.

Safety-net hospitals and clinics care for a population heavily skewed toward the poor, recent immigrants and people of color. The budgets of these places are forever tight. And anyone who works in them could tell you that illness in our patients isn’t just a biological phenomenon. It’s the manifestation of social inequality in people’s bodies.

Neglecting this fact can make otherwise meticulous care fail. That’s why, on one busy night, a medical student on my team is scouring websites and LinkedIn. She’s not shirking her duties. In fact, she’s one of the best students I’ve ever taught.

This week she’s caring for a retired low-wage worker with strokes and likely early dementia who was found sleeping in the street. He abandoned his rent-controlled apartment when electrolyte and kidney problems triggered a period of severe confusion that has since been resolved. Now, with little savings, he has nowhere to go. A respite center can receive patients like him when it has vacancies. The alternative is a shelter bed. He’s nearly 90 years old.

Medical textbooks usually don’t discuss fixing your patient’s housing. They seldom include making sure your patient has enough food and some way to get to a clinic. But textbooks miss what my med students don’t: that people die for lack of these basics.

People struggle to keep wounds clean. Their medications get stolen. They sicken from poor diet, undervaccination and repeated psychological trauma. Forced to focus on short-term survival and often lacking cellphones, they miss appointments for everything from Pap smears to chemotherapy. They fall ill in myriad ways — and fall through the cracks in just as many.

Early in his hospitalization, our retired patient mentions a daughter, from whom he’s been estranged for years. He doesn’t know any contact details, just her name. It’s a long shot, but we wonder if she can take him in.

The med student has one mission: find her.

I love reading about medical advances. I’m blown away that with a brain implant, a person who’s paralyzed can move a robotic arm and that surgeons recently transplanted a genetically modified pig kidney into a man on dialysis. This is the best of American innovation and cause for celebration. But breakthroughs like these won’t fix the fact that despite spending the highest percentage of its G.D.P. on health care among O.E.C.D. nations, the United States has a life expectancy years lower than comparable nations—the U.K. and Canada— and a rate of preventable death far higher.

The solution to that problem is messy, incremental, protean and inglorious. It requires massive investment in housing, addiction treatment, free and low-barrier health care and social services. It calls for just as much innovation in the social realm as in the biomedical, for acknowledgment that inequities — based on race, class, primary language and other categories — mediate how disease becomes embodied. If health care is interpreted in the truest sense of caring for people’s health, it must be a practice that extends well beyond the boundaries of hospitals and clinics.

Meanwhile, on the ground, we make do. Though the social workers are excellent and try valiantly, there are too few of them, both in my hospital and throughout a country that devalues and underfunds their profession. And so the medical student spends hours helping the family of a newly arrived Filipino immigrant navigate the health insurance system. Without her efforts, he wouldn’t get treatment for acute hepatitis C. Another patient, who is in her 20s, can’t afford rent after losing her job because of repeated hospitalizations for pancreatitis — but she can’t get the pancreatic operation she needs without a home in which to recuperate. I phone an eviction defense lawyer friend; the young woman eventually gets surgery.

Sorting out housing and insurance isn’t the best use of my skill set or that of the medical students and residents, but our efforts can be rewarding. The internet turned up the work email of the daughter of the retired man. Her house was a little cramped with his grandchildren, she said, but she would make room. The medical student came in beaming.

In these cases we succeeded; in many others we don’t. Safety-net hospitals can feel like the rapids foreshadowing a waterfall, the final common destination to which people facing inequities are swept by forces beyond their control. We try our hardest to fish them out, but sometimes we can’t do much more than toss them a life jacket or maybe a barrel and hope for the best.

I used to teach residents about the principles of internal medicine — sodium disturbances, delirium management, antibiotics. I still do, but these days I also teach about other topics — tapping community resources, thinking creatively about barriers and troubleshooting how our patients can continue to get better after leaving the supports of the hospital.

When we debrief, residents tell me how much they struggle with the moral dissonance of working in a system in which the best medicine they can provide often falls short. They’re right about how much it hurts, so I don’t know exactly what to say to them. Perhaps I never will.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Why California Doesn’t Know How Many People Are Dying While Homeless

Nearly a decade ago, David Modersbach had what he thought was a straightforward question: How many unhoused people had died that year?

The grants manager and his team at Alameda County Health Care for the Homeless knew people were dying on the streets, but they wanted more than anecdotal evidence; they wanted data that could show them the big picture and help them hone their strategies.

They queried the coroner’s bureau and were stunned by the response: only a single death had been reported.

“We realized there’s a lot of work to do,” Modersbach said.

What followed was a bootstrap campaign to fill the data gap. It took years, and the work was sometimes lonely, often tedious and consistently heartbreaking. When the team finally released its first report in 2022, detailing deaths from 2018–20, they counted 195 people in Alameda County who died while homeless in 2018, plus another 189 people with recent histories of homelessness whose housing status couldn’t be verified at their time of death.

As more Californians have fallen into homelessness — a number greater than 181,000 at last count (PDF) — more have died while unhoused, but the state’s ability to track these deaths and assess the scope of the problem hasn’t kept pace.

Spurred in part by Alameda County’s efforts, which are considered a national model for the field, the state recently began taking steps toward collecting this data. In 2022, California added a field to death records for homelessness status, and this year, a law went into effect that empowers counties to set up homeless death review committees to determine the root causes of homeless mortality.

California is among several jurisdictions across the country seeking this data. The pandemic put a spotlight on the health vulnerabilities accompanying homelessness, and that has led to growing national interest in the topic, said Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy for the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. A recent study from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and NYU found the death rate of people experiencing homelessness increased 238% between 2011 and 2020.

“One of the things that hopefully we took away from COVID is that homelessness is a public health issue,” she said. “Not only is living unhoused very dangerous and high risk for people experiencing homelessness, this isn’t good for communities either.”

Researchers said the data is critical in assessing whether the state’s public health interventions for people on the streets work.

“That is how we work to change things,” said Dr. Margot Kushel, director of the UCSF Benioff Housing and Homelessness Initiative. “One of the problems with not reporting it is that it makes it harder to act.”

But getting statewide — let alone national — data detailing the number of unhoused deaths requires meticulous reporting on the part of local agencies. In the case of Alameda County, it was a system Modersbach had to build from scratch.

How they count

For each homeless mortality report, Modersbach and his colleagues first scour thousands of county death records, searching for clues that suggest homelessness: words like “encampment,” “tent” and “shelter.” They then cross reference that list with a database of everyone in the county who has experienced homelessness in the past five years — itself a bespoke repository that draws on the agency’s healthcare data and records from the county’s shelter and homeless assistance programs. To capture anyone they might miss, they cull information from service providers, media accounts and a public online portal for submitting tips about deaths.

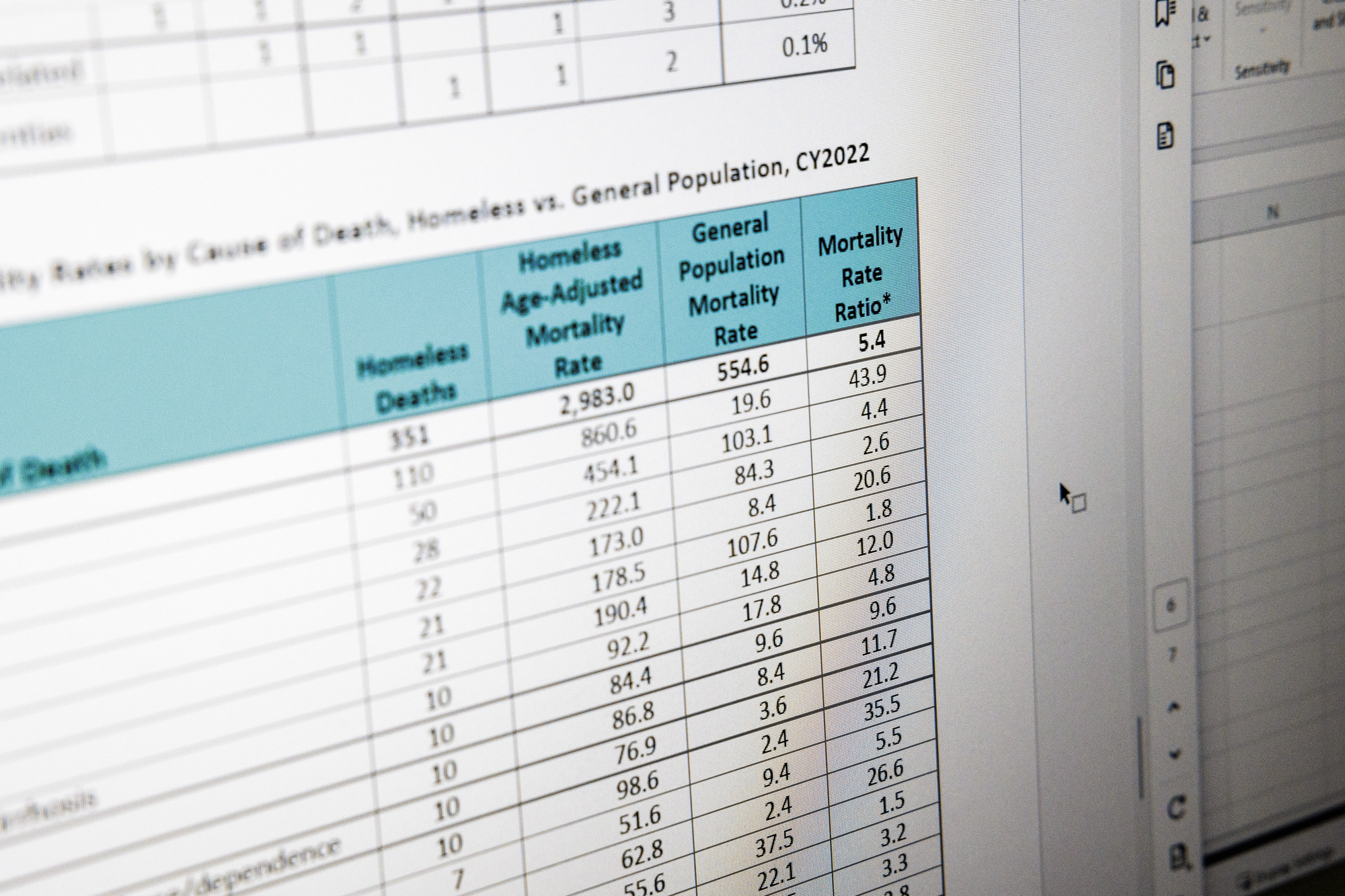

Since they began tracking homeless mortality, the team has traced an 80% increase in the number of deaths, which rose from 195 in 2018 to 351 in 2022, the most recent year for which data was reported. Over the same period, homelessness in the county jumped by nearly the same amount — or 77% — from 5,496 people to 9,747.

Behind the numbers are snapshots of how and where people are dying. A body found in a car. An overdose at an encampment. People mangled by cars or trains; others charred. Modersbach finds the tableau at once unsurprising and shocking.

“We see the same inequities in our mortality data that are reflected in homelessness,” he said. Black people are overrepresented, comprising 48% of the unhoused population and accounting for 44% of the deaths — though they represent only 19% of deaths in the county’s general population.

People who are unhoused die at five times the rate of those with housing and do so more than two decades sooner — at an average age of 52.

The data shapes decisions

Most of the deaths could be prevented, said Amy Garlin, Medical Director for Alameda County Health Care for the Homeless.

“You could say almost all of these deaths are preventable if you go far enough upstream,” Garlin said.

The largest share, 44% of the deaths among the homeless population, were caused by acute or chronic medical conditions, like heart disease, cancer, diabetes and infections. Some of those appear to have been more immediately avoidable, Garlin said. “If these people had had medical care, they may not have died this year.”

At an encampment along East 12th Street in Oakland, Angel Gonzalez, 40, remembered the friends he’d known there who had died. An asthma attack claimed one, exposure another and a third succumbed to a fever. Though Gonzalez said he didn’t know what had caused the fever, he said people are often sick, and rat bites are common.

“Health-wise here, it’s bad,” he said.

There’s frequent violence, too. Gonzalez described a drive-by shooting that killed one friend and wounded others. But what claims most people in the camp, he and others said, is overdoses.

“The fentanyl is killing mostly everybody,” Gonzalez said, explaining that people unwittingly use fentanyl-laced meth or other drugs. “It’s kind of scary.”

The mortality data compiled by Modersbach’s team reflects this, with an alarming rate of overdose deaths among unhoused residents that is 44 times the general population’s. In response, they’ve expanded their harm reduction services, focusing on naloxone distribution and installing dispensers in shelters.

At the East 12th Street camp, Gonzalez pointed out a purple dispenser on the street corner. Though Modersbach’s team had not installed it, it still proved lifesaving, Gonzalez said, when a friend recently used one of the naloxone sprays to reverse an overdose.

Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless received a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2023 to fund overdose response, a key part of their strategy to reduce mortality, and Modersbach credits their data for helping them get it.

In Minnesota, the only state with a statewide robust system for tracking homeless mortality, public health officials took a similar approach. A report on deaths between 2017 and 2021 showed unhoused people in the state were 10 times more likely than the general population to die of an overdose. Shortly after that data was released in 2023, state lawmakers passed drug overdose prevention legislation that expanded harm reduction and housing programs for people experiencing homelessness, decriminalized drug paraphernalia — a first for the U.S. — and funded “safe recovery sites” that offer clean needles, fentanyl testing and will eventually offer supervised drug consumption.

“Having the data was really useful in making the case for some of those things, both with legislators and with the public and advocates,” said Josh Leopold, senior advisor on health, homelessness and housing at the Minnesota Department of Health.

Alameda County’s latest homeless mortality report is now prompting the team to focus on how to extend palliative care services to unhoused people with terminal illnesses. Garlin estimates almost one-fifth of those who died in 2022 would likely have been eligible for hospice care.

What’s next in the ‘labor of love’

Modersbach’s team is also working to automate the most tedious aspects of compiling the county’s homeless mortality report and aims to launch a public dashboard later this year that will make information available quarterly.

“The biggest challenge is that we do not have timely data that we can act upon more quickly because of the workarounds that we have to do to get an accurate count,” Modersbach said. “We’re almost always looking backwards.”

The county’s latest tally, for 2022, was released at the beginning of 2024.

Santa Cruz, San Diego, San Mateo, Sacramento, Los Angeles and San Francisco are among the counties with varying degrees of reporting on homeless deaths. In Santa Clara County, an early champion of this work, a public dashboard tracking homeless mortality is updated nightly. A spokesperson for the Medical Examiner’s Office credited its partnership with a third-party vendor with allowing it to return results so quickly. So far this year, the dashboard listed 51 deaths.

Across the country, about two dozen jurisdictions have homeless mortality reports that are issued with some regularity, according to DiPietro of the National Healthcare for the Homeless Council, which tracks these efforts. But because the reporting isn’t standardized, it’s difficult to draw comparisons between them, she said.

In California, despite the recent efforts to improve this tracking, limited resources will likely continue to hamper the reporting of homeless deaths. Since 2022, when the state added a field on death reports to indicate a person’s housing status, Modersbach has seen some evidence people are filling it out, but he worries many unhoused deaths will continue to go uncounted around the state because the funeral directors, coroners and physicians filling out the reports don’t often have the resources to determine whether someone was housed.

“This is a lonely, costly battle to just put all this information together, not a funded mandate,” he said. “It’s kind of a labor of love.”

In counties with well-established systems for tracking these deaths, Modersbach hopes AB 271, by Assemblymember Sharon Quirk-Silva (D-La Palma), will make a difference. The new law allows counties to create homeless death review committees and access sensitive information about people who died. The data, which includes medical, mental health and criminal records, goes beyond what Modersbach and his team have so far been able to collect, giving them greater insight into the circumstances surrounding a person’s death.

Alameda County assembled its death review committee last year, bringing together officials from several county agencies, homeless service providers and formerly unhoused people with the aim of finding ways to keep more people experiencing homelessness alive.

“It’s just getting started,” Modersbach said, “but this is the future for us.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Older people who are homeless need better access to hospice and palliative care

Most people may not wish to devote much time to thinking about their death. However, it’s an unfortunate fact that the entry point into experiences or conversations around death and end-of-life care can happen abruptly.

An unexpected death or a terminal diagnosis can leave people ill-equipped to navigate what often feels like uncharted territory of navigating end-of-life care, bereavement and grief.

The challenging realities surrounding end-of-life care are especially difficult for older people experiencing homelessness. For these older adults, intersectional and compounding experiences of oppression, such as poverty, racial disparities and ageism, create barriers to accessing hospice care.

Misconceptions about hospice care

The need for end-of-life and palliative services for unhoused people will likely continue to grow as the population experiencing homelessness grows and ages.

Currently only 16 to 30 per cent of Canadians have access to hospice and palliative care services, and 34 per cent of Canadians are not clear on who is eligible or who should utilize hospice services. In response, May 7-13 marks National Hospice Palliative Care week, which is aimed at increasing awareness about hospice care in Canada.

The misconceptions about hospice care have had a direct impact on the engagement of services for the public, but also for Indigenous communities and for older adults experiencing homelessness.

Efforts to increase awareness about hospice often neglect the most vulnerable populations. Future efforts must merge education and awareness with intersectionality, which takes into consideration the intersections of inequities that impact unhoused older adults.

Hospice care focuses on addressing the full spectrum of a patient’s physical, emotional, social and spiritual experiences and needs. A common misconception is that hospice is exclusively a location or place where people go to die. Contrary to this notion, hospice is a service that is provided in various settings including within one’s home, long-term care facilities, hospice centres or within a hospital.

End-of-life care

While many Canadians prefer to die at home, older people experiencing homelessness do not have the same opportunities for end-of-life care options, and as a result many unhoused older people die in the hospital or institutional settings.

Family and friends often play an essential role in caring and advocating for a loved one during their end-of-life process. We can only hope to have loved ones by our side during these final stages; however, that is not the reality for many unhoused community members who do not have the option to die at home with loved ones.

Older people experiencing homelessness are especially vulnerable due to limited family or social support networks. Lack of social support can result in unhoused older people feeling isolated and fearful about dying alone or anonymously.

A core focus of palliative care is on easing symptoms and increasing quality of life for people who have a serious or chronic illness, and not solely for those who are dying. Palliative care can be a valuable form of health care for older people experiencing homelessness, as it can offer a tailored approach to managing multiple chronic or terminal illnesses, which are prevalent among unhoused older people.

Palliative care that takes place in a hospital setting can decrease end-of-life care costs by nearly 50 per cent by reducing intensive care unit admissions and unnecessary intervention procedures.

We believe it is valuable to consider that if end-of-life care costs were reduced by using palliative care practices, the cost savings could be used to fund services that directly support unhoused older adults, such as increased affordable housing options.

Aging in the right place

As members of the Aging in the Right Place project research team at Simon Fraser University, we are working to better understand what aging and dying in the right place means to unhoused older adults in two sites providing end-of-life care in Vancouver.

May’s Place Hospice, which is in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, provides end-of-life care for community members in that part of the city. May’s Place has created a communal, home-like environment with private rooms, meals provided three times a day, 24-hour nursing care, a smoking lounge and family gathering space.

Another inpatient hospice setting in Vancouver is Cottage Hospice, located in a 1924 heritage building. Patients have a view of the North Shore mountains and are close to the water. Cottage Hospice and May’s place provide the same types of hospice palliative care support, and both care for older patients experiencing homelessness, but serve different populations based on their location and setting, demonstrating that hospice and palliative care is not a one-size-fits all approach.

The Aging in the Right Place project captures the perspectives and lived experiences of older people experiencing homelessness through integrating photovoice interview research methods as well as data collection methods that focused on the hospice setting, the neighbourhood, and experiences of staff who work to support unhoused older people. Photovoice is a method used in community-based research in which participants use photo taking and storytelling to document their own perspectives and experiences.

In the Vancouver area where we work — also known as the land that belongs to the Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam) and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) people — and throughout the province, colonization and colonial medical models have had lasting and detrimental impacts on Indigenous knowledge and traditional practices around death and dying for First Nation communities.

One example of these impacts is that current hospice models may not reflect culturally relevant care models. Hospice organizations throughout B.C. should prioritize increasing policy and practice for Indigenous groups to ensure safety and culturally relevant care are implemented. Ensuring accessibility to hospice and palliative care is one step towards dismantling these barriers for Indigenous populations.

B.C. can turn to the Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless (PEACH) service fostered by Inner City Health Associates (ICHA) in Toronto as an example. PEACH is taking a diverse and innovative approach to providing palliative care among the homeless and vulnerable populations, including Indigenous communities and older adults. Innovative and culturally sensitive services such as these, are a step in the right direction to providing better end-of-life care to older adults experiencing homelessness.

It is crucial that we make hospice and palliative care services available to all community members, especially with the aging population and an increase in chronic illnesses throughout Canada.

In addition to supporting community members, hospice and palliative care should focus efforts on tailoring approaches to provide culturally relevant care, increasing staff education about the lived experiences of older people experiencing homelessness, and creating safe and accessible services in B.C. for marginalized communities.

We must actively dismantle misconceptions about the role of hospice and palliative care through education and awareness to facilitate appropriate service delivery and use for diverse populations.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Unhoused Americans have few places to turn when death is near

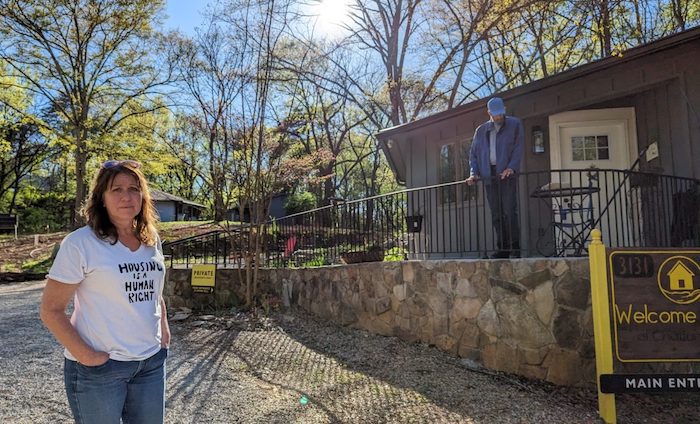

A few years ago, Mark Adams was diagnosed with colon cancer. His doctors didn’t want to operate, he said, because his recovery could be too risky without a clean place to recuperate. He was living on the street.

Soon, it was too late, his cancer too far along. That’s what they discovered after he moved into Welcome Home, a facility offering long-term medical respite and end-of-life care for unhoused adults.

Instead of getting better, he’ll likely live out the rest of his days there – one of a small number of places in the United States that offers unhoused people a comfortable and dignified option when they are terminally ill.

Sufficient end-of-life care in the United States is a growing problem for the general population, as America’s aging baby boomer generation needs more intensive and expensive help and supply isn’t keeping up. For many unhoused adults — who frequently lack a strong social safety net — long-term medical or hospice care are effectively inaccessible. In the absence of publicly funded solutions, private organizations and nonprofits are trying to plug the gaps, but the patchwork network of end-of-life care homes is far too limited to address the need.

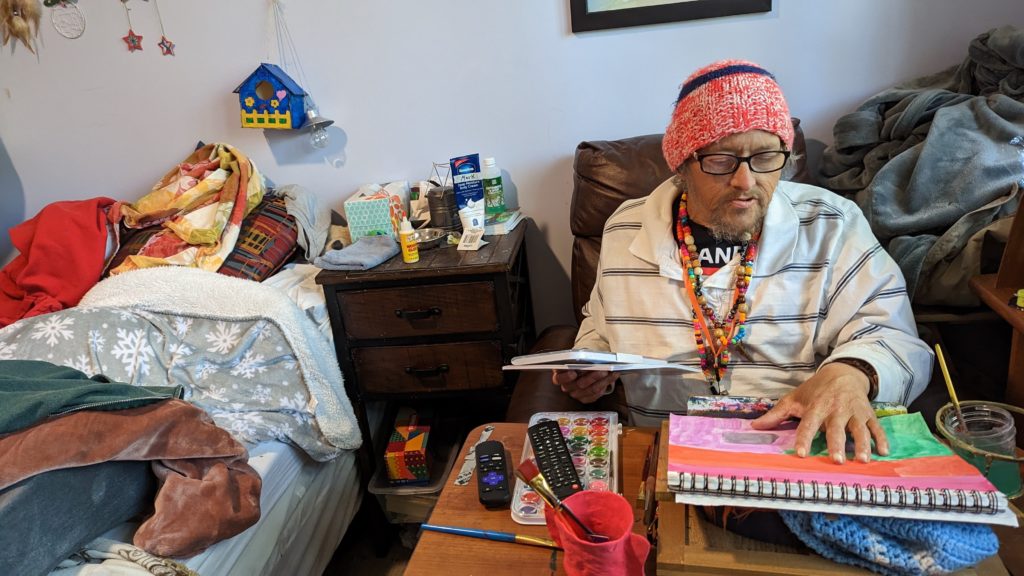

On a mild spring Sunday, Adams worked on a painting in his cozy, eclectic room – filled with vinyl records, potted plants and his own art – while his friend Clint Jackson relaxed nearby. Up the hill, Standrew Parker rested on a wrought iron chair in his yard, soaking up the early afternoon sun and chatting with his new roommate, Heidi Motley. Parker, 40, and Motley, 58, are staying there while undergoing treatment for cancer.

Across the country, there are a handful of facilities like Welcome Home, which sits on nearly five forested acres in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Some 1,300 miles west, there’s Denver’s Rocky Mountain Refuge for End of Life Care. Salt Lake City is home to The Inn Between, while Washington, D.C. has Joseph’s House. In Sacramento, Joshua’s House plans to open its doors this fall. Dozens more offer medical respite beds, generally for those undergoing long-term medical treatment. But outside of these organizations, experts told the PBS NewsHour that there are few other places where people experiencing homelessness can go for end-of-life or hospice care.

These facilities aren’t massive – Welcome Home has three medical respite rooms in addition to its four hospice beds, and is opening another house with an additional three rooms this month. Rocky Mountain Refuge, the smallest and newest of the group, has three beds solely for end-of-life care.

The need for those beds is great: People who are homeless are at far higher risk for many illnesses and conditions, such as heart disease. Medical research also shows that unhoused people’s bodies have often aged as if they were at least a decade older.

Being without a home is itself “a life-limiting diagnosis,” as Hannah Murphy Buc, a researcher who studies palliative and end-of-life care for people experiencing homelessness, wrote in the journal Caring for the Ages.

When someone is already in poor health, there are basic obstacles of living without a home – not having access to a fridge to store medications or the ability to secure narcotics for pain management, for instance. Some people without permanent addresses, like Adams, have reported they were denied treatment for their cancer due to the physical demands of recovery.

“Hospice and palliative care, but particularly hospice, is completely reliant on having a place to receive it,” Murphy Buc told the NewsHour.

For Adams, 51, living at Welcome Home has been life-changing, even though he often feels sick and he says he knows the cancer will likely kill him.

“I feel good here. I feel like I’m welcome here,” he said.

What we know about deaths among the unhoused

There is no official national data on where, when and how people experiencing homelessness die. According to an analysis by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC), at least 5,800 people died while experiencing homelessness in 2018. That’s almost certainly an undercount, and the report noted the actual number could have been anywhere between 17,500 and 46,500 deaths for that year.

With more people expected to become homeless and as that population ages, that mortality figure expected to rise, said Dr. Margot Kushel, director of UCSF’s Center for Vulnerable Populations and Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative.

“The truth of the matter is most of the country is entirely unprepared for this,” Kushel said.

Local reports can help explain what’s happening currently to those who can’t access end-of-life care. Across several months in 2021, deaths among unhoused people in San Francisco occurred primarily outdoors, in places like encampments, vehicles or on the street, a report from the NHCHC found. Others died in medical facilities; motel rooms, either rented by the person or as a shelter-provided space; other people’s homes; and homeless shelters.

Similarly, in King County, Washington, about half of the people experiencing homelessness who died in 2018 perished outdoors, according to a report from the council. Only 26 of the 194 deaths occurred in residences.

A 2022 report from the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless found that among the unhoused individuals who die of so-called “natural causes,” 30 percent died in hospitals or other medical facilities, and 25 percent died outside.

“That means under a bridge, on a sidewalk, behind a bush, in a tent,” said Brother James Patrick Hall, the executive director of Rocky Mountain Refuge.

While in prior decades people experiencing homelessness may have died from acute causes, such as violence or illness, the aging population of unhoused people is now living with the chronic conditions that plague many seniors, such as COPD, heart failure, strokes and cancer.

“These folks often need a lot of personal care. They have pain issues … It’s like a disaster, to be honest,” Kushel said. “What we found in Oakland is [that] a lot of folks just died on the street, short of breath, in pain, incontinent.” Others were admitted to hospitals, and some ended up at nursing homes or acute care facilities, “but it wasn’t where they wanted to be.”

When given a choice, people overwhelmingly want to die at home, according to Murphy Buc. Death at home can lead to healing in relationships and help soothe those left behind. But even when that’s an option, it can be draining for those doing the caretaking, she noted, even with hospice nurses visiting a few times a week.

In the U.S., “we don’t do death well,” Murphy Buc said.

The problem of older people dying on the streets, in motel rooms and in cars is the ultimate result of disinvestment in affordable housing, skilled nursing care and health care, experts at the NHCHC told the PBS NewsHour.

It’s not that people who become homeless are falling through the cracks, said Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy at the NHCHC. Instead, people are often forced into “gaping caverns” where underfunded social safety nets, such as Medicaid and public housing, fail to catch them.

An older adult who has worked as a manual laborer her entire life might have a stroke and lose employment, be unable to pay rent and end up without a home, said Caitlin Synovec, senior program manager with the council’s medical respite team. Shelters frequently can’t help people with enhanced medical needs, so they have nowhere else to turn.

The unhoused population is also disproportionately vulnerable, low-income and people of color — all groups who have historically experienced disparities and may distrust the nation’s health care and social services systems.

In addition to that added barrier, people may just not know they have medical respite and end-of-life care options, Murphy Buc said. Many of the current residents of these facilities were referred there by health care professionals or social workers, but had not previously heard of them.

‘Health care isn’t housing’

Having a home, in and of itself, can be considered a form of health care, advocates say. Those who work or volunteer at care homes sometimes witness very sick people make dramatic recoveries simply because they have a safe, comfortable and stress-free place to live.

Though each facility operates slightly differently, these homes offer more than just a physical address, providing services like palliative care, case management and transportation. Volunteers and staff can remind residents to take medicine, ask how they’re feeling, and, crucially, drive them to appointments.

Before Standrew Parker lived at Welcome Home, he would have to travel to the hospital from his mother’s house to receive five days of cancer treatment every few weeks. In addition to being an unwelcoming environment, her house was about 45 minutes away by rideshare, which cost around $60 to $70, he said. To avoid the trip back and forth, he would instead often spend his days living outside the hospital.

“We didn’t have that money. So I was in and out, just like hanging out. If I had multiple appointments for days on end there, I just [stayed outside the hospital]. I would have to or I wouldn’t get the correct shots or the treatment,” Parker said.

Now, volunteers drive him to and from his treatments, and during his weeks off from chemotherapy, he recuperates in his room at Welcome Home. Beyond the care he receives, the empathy and compassion from staff and volunteers helped shift his entire perspective on healing.

“It’s like a world of difference between surviving and actually being able to get well,” he said.

A crucial goal of each facility is to establish a sense of normalcy for people whose lives have been thrown out of balance. Welcome Home serves dinner every night, where residents can gather and rib one another. People living at The Inn Between can join the resident council, which offers both community and a way to effect change, such as what times coffee is available. For the patients who recover enough, these homes can help them adjust to life outside of the facility so they can leave.

When NHCHC began their medical respite programs in the late 1980s, they were originally intended as short-term stabilization. However, some of the programs that specialize in medical respite have begun to consider incorporating end-of-life and hospice care into their models to fill the gap, said Julia Dobbins, director of medical respite at NHCHC’s National Institute for Medical Respite Care.

In contrast, patients without somewhere to go sometimes cycle between a hospital and the street, being readmitted when their problems are acute enough to warrant immediate care, and released when they’re stabilized, Murphy Buc said.

Sending still-sick people back to the streets is called “patient dumping,” and “it’s horrible,” Kushel said. But, she added, the solution can’t be that people live at a hospital for months on end until they die. That’s an inefficient use of resources, not to mention that it’s unlikely to be where a patient wants to spend the rest of her life.

Hospitals don’t want to deny people care, Kushel said. When she heard about Adams’ doctors refusing to treat his cancer while he was experiencing homelessness, she noted that his situation was not uncommon. Doctors worry about harming people who don’t have access to long-term, safe and clean care, but it doesn’t make it an easy decision.

“It happens all the time,” Kushel said. “And when you speak to the surgeons, they actually feel terrible about it.”

In the long run, even medical respite doesn’t solve the problem of where people can live, said NHCHC’s DiPietro.

“We often say housing is health care. Absolutely,” she said. “Unfortunately, health care isn’t housing.”

For many, providing medical respite or end-of-life care to people experiencing homelessness with their own limited resources can feel like a Sisyphean task.

For every person given a bed, there are countless others who need and can’t access one. Each organization can only serve their local community, leaving hundreds of people or more to die on the street nationally each year.

Beyond what the organizations receive from state and local funding, there’s little — if any — government funding for long-term medical care or end-of-life care for people with no fixed address. These organizations’ funding models are largely reliant on grants and donations, without long-term stability.

“It’s local advocates who are seeing the suffering of their community members, and so they’re creating these programs that are funded by the good of people’s hearts, and that’s it,” Dobbins said.

Rocky Mountain Refuge, which opened its doors a little over a year ago, struggles to find enough funding to stay open, Hall said. That’s an experience echoed across the country.

“One of the stresses for us here is, every year, are we going to be able to keep our doors open because of the funding?” said Kowshara Thomas, director of Joseph’s House in Washington, D.C.

Founded in 1990 during the HIV/AIDS crisis, the three-story house in a quiet residential neighborhood has served community members dying of the disease for decades. This year, however, they lost a major grant that comprised 30 percent of their revenue, which worries Thomas. Other medical respites in the D.C. area receive Medicaid funding, and larger organizations are often better positioned to write grants and secure funding. But Thomas says Joseph’s House, with only eight beds, is too small to follow suit.

The organization has largely, though not entirely, pivoted from end-of-life care to medical respite, something Thomas sees as both a result of better health among their community and a way for them to provide continuing care for people after they’re discharged. Joseph’s House has around 25 community members for whom they provide supportive services.

Thomas is also proud of the community that Joseph’s House anchors, with former residents coming back for meetings, social time and sometimes additional long-term or end-of-life care.

“Having a place where you can feel safe and get the support — the medical and the psychosocial support — is really what helps our community,” Thomas said. “Joseph’s House is, for some of our residents, the first time they’ve ever had family or felt like they belonged somewhere and they could just be who they are.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

New end-of-life doula services focus on rural, houseless populations

— OHSU School of Nursing alum aims to make end-of-life a social, not medical event

By Christi Richardson-Zboralski

As a hospice nurse, Erin Collins, M.N.E., RN, observed that many of her patients were afraid of dying, in denial of their imminent death, and consequently unprepared for it.

Now, she’s seeking to change that: Collins’ new organization, The Peaceful Presence Project, views compassionate end-of-life care as a basic human right, and is creating a social death care movement through education for clinicians, volunteer-based programs, and an innovative concept called end-of-life doulas.

“As health care providers, it is not always about saving lives at all costs, it’s about supporting someone to live and die well,” Collins said. “That often includes where they want to die and who they want to be present.”

Collins is a certified hospice and palliative care nurse with 16 years’ experience in oncology and end-of-life care. She recently completed a Master of Science in Nursing Education at the OHSU School of Nursing, Portland campus, and was selected as a 2022 Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholar.

The mission of The Peaceful Presence Project is to reimagine the way communities talk about, plan for and experience serious and terminal illnesses. Its approach is based on the compassionate communities model of end-of-life care, which asserts people facing serious illness should spend 5% of their time with a health care professional, and views the end-of-life as a social event with a medical component — rather than the other way around. Their doula program helps fill the 95% of time people aren’t face-to-face with their health care provider.

Doulas are people who are trained to serve. Many people are familiar with birth and postpartum doulas, who serve families during and after the birth of a child. End-of-life or death doulas serve families during the end of the life cycle. End-of-life doula courses provide training in how to be a present and active listener; create a calm and compassionate environment; and provide non-medical comfort measures, such as distraction, guided imagery and repositioning to help alleviate symptoms. Trained volunteers may help with legacy projects, including collages, audio or video recordings, and other ways to display physical objects. When needed, they help with memorial planning.

The trainings emphasize how to facilitate compassionate discussions about death-related topics. In 2023, Collins will develop a continuing education program for rural health care workers through her Sojourns Scholar project to improve access to palliative care in communities where specialists often don’t exist.

Community-based end-of-life support

Lily Myers Kaplan speaks highly of The Peaceful Presence doula training she took in 2022. Meyers Kaplan is author of two books on loss and legacy, co-founder of The Spirit of Resh Foundation, the Ashland Death Café and The Living/Dying Alliance of Southern Oregon.

“There was a particular session on approaching end-of-life with veterans, which helped me see the need for diverse approaches to different populations. The difference in end-of-life support between those who have lived in a rural setting, caring for the land, or being actively reliant on their physicality versus someone who has had a more traditional or urban life is quite distinct.

“For example, caregivers who may be responsible for vast swaths of land — anywhere from 20 to 80 acres or more — need support from others who understand their needs,” said Myers Kaplan, who lives in the Applegate Valley, a rural area of Oregon that includes large stretches of land that provide solitude and a level of independence that most urban lifestyles don’t experience.

A caregiver in Depoe Bay reluctantly accepted help from The Peaceful Presence Project after his wife got him on board. After several long years of treatment and many ups and downs, Ray Burleigh’s adult daughter, Becky, had reached a point in her cancer treatment where it no longer worked. Burleigh had strong doubts when the hospice nurse brought up the topic. However, his wife, Jeni, said yes to the help.

With the support of two death doulas from The Peaceful Presence Project, Elizabeth and Erin, the Burleighs found some measure of relief. The death doulas told the family they would bring community support from around the Bend area.

“I was still not convinced. We needed practical help. Becky’s house is hard to heat and she was concerned they were spending too much money on keeping the house warm. It’s heated by a wood stove,” said Ray. “I told them to bring us some wood, not expecting anything. Two nights later, a truckload of wood came — not just one bundle, a truckload. I was shocked! We couldn’t have done this without Elizabeth and the doulas.”

Without the doulas’ help, Ray said they would have had to put Becky in the hospital, and possibly ended up sick themselves.

“The doulas provided night-shift help because we weren’t getting any sleep. They helped with groceries, created a schedule for visiting hours, and the fire,” he said.

Elizabeth and Erin identified 25 people in the city of Bend who were willing to help them out, including neighbors, and many people who are now friends of the Burleighs. Jeni’s family from the same area were also there to help.

Because of his time alongside these doulas, Ray has decided to take The Peaceful Presence Project doula training.

End-of-life care for under-resourced communities

Lora Munn, a yoga teacher who is National End-of-life Doula Alliance proficient, took The Peaceful Presence Project training in 2021.

“End-of-life care is not only being talked about in rural communities, but also actually being spread throughout rural communities thanks to the folks at The Peaceful Presence Project,” she said.

Munn lives in White Salmon, Washington, and serves all communities located in the Columbia River Gorge. She said she understands that “folks in rural and houseless communities may not have access to resources for the dying and their loved ones in the same way that urban communities do. Because of my education and training through The PPP, I am able to provide these necessary services to my small community. Through my training, I learned how to provide compassionate care for all beings, regardless of housing status or location.”

Because palliative and end-of-life care resources are sparse within rural and houseless communities, Collins and her team facilitate advance care planning to encourage these populations, and others, to think about their end-of-life experience.

“Parts of the state where there is no hospice care or even palliative care need more resources, and one way to address that is to have support embedded in the community,” Collins said.

Through two grant-funded projects, doulas and public health interns have been trained to hold advance care planning “pop-ups” at a navigation center for people experiencing homelessness, as well as in rural health clinics. Navigation centers are low-barrier emergency shelters that are open seven days per week and connect individuals and families with health services, permanent housing and public benefits.

Conversations about what their death experiences could entail are uncommon for people experiencing homelessness, Collins said. The general population tends to choose a spouse or family member as their medical decision-maker. But within the homeless population, a non-family member or someone in their so-called street family is more likely to be their choice. In the absence of a named decision-maker, the hospital may call an estranged family member or someone with whom they are not in contact.

“Equitable care means providing equitable services,” Collins said. “This includes advance care planning for people who are experiencing homelessness. We found that many of these folks have never been asked what their preferences are at end-of-life.”

Educating health care professionals about palliative care

Although it’s important to educate people in the community, it doesn’t stop there. Collins emphasizes the importance of education for all health professionals about serious and terminal illnesses — which is not traditionally an in-depth part of the health care curriculum.

“Nurses and physicians don’t always know how to have those conversations. Palliative care should be part of all health education,” Collins said. “Not just a specialty, but a standard part of education.”

To get participants thinking about ways to support their patients, The Peaceful Presence Project asks them to reflect on key questions: How do you ask someone about what they want if they are dying? How can you have a compassionate conversation?

“Training in communication skills allows you to feel empowered as a provider and as a fellow human being,” said Eriko Onishi, M.D., an assistant professor of family medicine in the OHSU School of Medicine and a palliative care physician at Salem Hospital. “It makes you a better listener through your professional sense of curiosity about other people. You feel as if you are truly walking alongside your patients, guiding them in the right direction, instead of just feeling the way blindly, guessing at each step.

“It’s important to understand that it isn’t about exercising power or control over patients,” Onishi continued. “Rather, it is using this powerful communication tool to support everyone involved, to help them to feel safe because the situation itself is under control.”

Onishi is passionate about the need for such conversation skills training.

“To be a clinician, both knowledge and communication skills are equally essential — it’s never a one-or-the-other choice,” Onishi said. “As a physician, my job is to provide medical guidance to the patient and their family, guided by the best intentions and a caring heart. If I cannot do all of these things, I cannot do my job.”

Ultimately, Collins said, it’s up to the individual patients to discuss how they want to experience their end-of-life, knowing that flexibility and adaptability are key. Having a plan is important, and when things don’t go according to plan, community-based support for death and dying can alleviate a stressful process for all involved — providing what people need to live and die well.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Older Homeless People Are At Great Risk of Dying

Research Describes a “Health Shock” from Losing Housing Later in Life

A quarter of the participants in a long-term study of older people experiencing homelessness in Oakland died within a few years of being enrolled, UC San Francisco researchers found.

The study, funded by the National Institute on Aging, recruited people who were 50 and older and homeless, and followed them for a median of 4.5 years. By interviewing people every six months about their health and housing status, researchers were able to examine how things like regaining housing, using drugs, and having various chronic conditions, such as diabetes, affected their risk of dying.

They found that people who first became homeless at age 50 or later were about 60 percent more likely to die than those who had become homeless earlier in life. But homelessness was a risk for everyone, and those who remained homeless were about 80 percent more likely to die than those who were able to return to housing.

Becoming homeless late in life is a major shock to the system.

The median age of death was 64.6 years old, and the most common causes of death for people in the study were heart disease (14.5 percent), cancer (14.5 percent), and drug overdose (12 percent).

“Becoming homeless late in life is a major shock to the system,” said Margot Kushel, MD, who directs the Benioff Housing and Homelessness Initiative and is a professor of Medicine at UCSF and senior author of the study published August 29, 2022 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“These untimely deaths highlight the critical need to prevent older adults from becoming homeless – and of intervening and rehousing those that do, quickly,” she said.

The study is unique for its prospective design. Previous studies of mortality in homeless populations were retrospective and drew information from medical records. By contrast, the current study – Health Outcomes of People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle agE (HOPE HOME) – followed a group of people, whether or not they received health care.

Many study participants had serious conditions that went untreated.

“We looked at how frequently people reported diagnosis of heart disease or cancer before dying of these diseases. It was really low,” said Rebecca Brown, MD, affiliated assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at UCSF. “We think this represents a lack of access to care and delayed diagnosis. Often, we didn’t even know people were ill because they didn’t report it in their six-month interviews. But we found it on their death certificates.”

Researchers went to great lengths to track down what happened to the people in the study when they missed check-ins and couldn’t otherwise be accounted for, including looking at photos of unidentified deaths at the coroner’s office, reviewing California state death records to match their participants’ names and dates of birth, querying emergency contacts, searching social media, and reading online obituaries.

They found that as of Dec. 31, 2021, 117 of the 450 people had died since the study began enrolling in 2013. Nearly 40 percent (45) occurred after the pandemic started in March of 2020, but just three of those deaths were from COVID-19. Participants entered the study in two waves, with 350 enrolled in 2013-14 and another 100 enrolled in 2017-18; 101 of the deaths were from the first wave, and 16 were from the second.

Mortality rates were high compared to the general Oakland population. The risk of dying was 3 times higher for men and 5 times higher for women, compared to people of the same age and sex in Oakland. The median age for participants entering the study was 58, and 80 percent were black; 76 percent were male, and 24 percent were female.

The study also contained detailed information about people’s use of drugs and alcohol, as well as their mental health. But drug and alcohol use itself was not independently associated with death.

“The streets are just no place to live,” said Johná Wilcoxen, 72, who spent more than a decade living in his car when he lost Section 8 housing because his children moved out. Through his ordeal he continued working as a plumber, which gave him a place to go during the day and money for food. “The more people as we can get off the street, the better,” he said.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Anger, sadness dominate day of mourning for homeless people who died in L.A. this year

By Gale Holland

A joyous New Orleans-style Second Line parade to honor the roughly 1,000 homeless people who have died in Los Angeles County this year turned to anger on Friday, as skid row mourners stopped at City Hall to denounce elected officials for not halting the growing death toll.

Dozens of skid row residents and advocates, all decked out in Mardi Gras beads and flying black, gold and purple balloons, chanted: “Three a day! Too many!” They waved their fists at the windows of City Hall, where a homeless man in his 50s was found dead Tuesday night.

The parade and angry demonstration were part of National Homeless Persons Memorial Day, marked in dozens of cities.

L.A.’s day of mourning began soberly at the James Wood Community Center with prayers, songs and the traditional recitation of the names of all people who died at skid row missions and programs. Later, advocates planned to release candles at Echo Park Lake, where dozens of people have been living and dying in tents over the past year.

The Los Angeles County Public Health found in October that deaths among homeless people have increased each year, from 536 in 2013 to 1,047 in 2018. The tally so far this year is 963, they said.

Pete White of the Los Angeles Community Action Network, the parade organizer, accused City Atty. Mike Feuer of hypocrisy for expressing sadness over the homeless man who died outside City Hall, the same week the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a landmark homelessness case that curbs police powers to clear homeless encampments when there aren’t enough shelter beds available.

Feuer and officials from several other cities and counties across California had asked the high court to either clarify or overturn the lower court ruling in City of Boise vs. Martin.

“The city attorney had the audacity to hold a press conference [about the death] … when, days before, his office was trying to figure out how to criminalize that man,” White said.

Rob Wilcox, the city attorney spokesman, said Feuer wanted the court to clarify the Boise ruling, not to extend police powers over homeless people.

Feuer announced the man’s death at a press conference on Wednesday morning.

“He was someone’s son. He might’ve been somebody’s dad or somebody’s brother,” Feuer said. “I don’t know. But I do know that he died alone, and if there is any truth to statistics, he is not alone.”

The first parade to mark National Homeless Persons Memorial Day took off at noon Friday from San Julian Park, accompanied by drums, a trumpet, a keyboard, bicycles festooned with beads and Christmas garlands, and a giant banner that included photos of skid row residents who had died. It was labeled “Death by neglect” and contained a dot map of every homeless death site in Los Angeles County in the past year.

Several singers led the crowd in “Wade in the Water” and other civil rights anthems. Stephanie Arnold Williams, a longtime skid row advocate, sped around the crowd in red sequined skates, live streaming the parade on Facebook from a solar-powered tablet strapped to her back.

“When death comes to the doorstep of City Hall, you know we must respond,” White said. “We are going to set up shrines to show our people didn’t die in vain.”

Several of the dead were remembered by name, including Rodney Evans, who died on skid row waiting to get housing.

The parade eventually returned to the skid row corner where Dwayne Fields, a longtime skid row street musician, was killed in August when his tent was set on fire in what authorities said was an intentional act.

Jonathan Early, 38, who also was homeless, has been charged in Fields’ death. The death — and that of his partner, Valarie Wertlow, a month later — underscores the stakes in the epidemic of homeless deaths.

“Fields was a Jimi Hendrix impersonator in Las Vegas, and he was a better guitarist than Jimi Hendrix,” Anderson said. “It’s like genius is being snuffed out. This is all of our fight.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!