By Paula Span

Last year, when an oncologist advised that Betty Chin might benefit frompalliative care, her son Kevin balked.

Mrs. Chin, a retired nurse’s aide who lives in Manhattan’s Chinatown, was undergoing treatment for a recurrence of colorectal cancer. Her family understood that radiation and chemotherapy wouldn’t cure her, but they hoped doctors could keep the cancer at bay, perhaps shrinking her tumor enough to allow surgery or simply buying her more time.

Mrs. Chin, 84, was in pain, fatigued and depressed. The radiation had led to diarrhea, and she needed a urinary catheter; her chemotherapy drugs caused nausea, vomiting and appetite loss.

Palliative care, which focuses on relieving the discomfort and distress of serious illness, might have helped. But Mr. Chin, 50, his mother’s primary caregiver, initially resisted the suggestion.

“The word ‘palliative,’ I thought of it as synonymous with hospice,” he said, echoing a common misperception. “I didn’t want to face that possibility. I didn’t think it was time yet.”

In the ensuing months, however, two more physicians recommended palliative care, so the Chins agreed to see the team at Mount Sinai Hospital.

They have become converts. “It was quite a relief,” Mr. Chin said. “Our doctor listened to everything: the pain, the catheter, the vomiting, the tiredness. You can’t bring up issues like this with an oncologist.”

Multiple prescriptions have made his mother more comfortable. A social worker helps the family grapple with home care schedules and insurance. Mr. Chin, who frequently translates for his Cantonese-speaking mother, can call nurses with questions at any hour.

Challenges remain — Mrs. Chin still isn’t eating much — but her son now wishes the family had agreed to palliative care earlier.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that many families know little about palliative care; it only became an approved medical specialty in 2007. It has grown rapidly in hospitals: More than 70 percent now offer palliative care services, including 90 percent of those with more than 300 beds.

But most ailing patients aren’t in hospitals, and don’t want to be. Outpatient services like Mount Sinai’s have been slower to take hold. A few hundred exist around the country, estimates Dr. Diane Meier, who directs the Center to Advance Palliative Care, which advocates better access to these services.

Dr. Meier said she expects that number to climb as the Affordable Care Act and Medicare continue to shift health care payments away from the fee-for-service model.

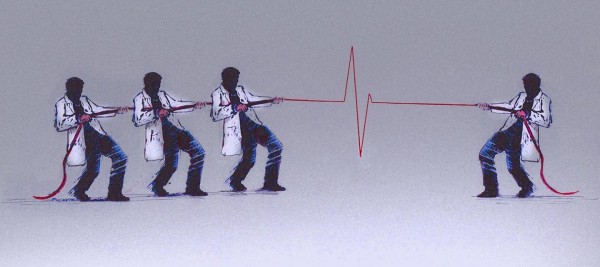

Because most people with serious illnesses are older, seniors and caregivers should understand that palliative care offers more care as needed, not less. Unlike hospice, patients can use it at any point in an illness — many will “graduate” as they recover — without forgoing curative treatment.

Like hospice, however, palliative care focuses on quality of life, providing emotional and spiritual support for patients and families, along with drugs and other remedies to ease symptoms. Its practitioners help patients explore the complex medical decisions they often face, then document their preferences.

It pays off for patients and families. In 2010, a randomized trial of 151 patients with metastatic lung cancer at Massachusetts General Hospital found that those who received early palliative care scored significantly higher on quality of life measures than those receiving standard care, and were less likely to suffer from depression.

They were also less likely to get aggressive end-of-life treatment like chemotherapy in their final weeks. Yet they survived several months longer.

Other studies have found similar benefits. Compared with control groups, palliative care patients get greater relief from the breathlessness associated with lung diseases; they’re less likely to spend time in intensive care units; they report greater satisfaction with care and higher spiritual well-being.

And they do better if they seek palliative care early. A new study conducted at the cancer center at the University of California, San Francisco, found that of 922 patients who had died, most in their 60s and 70s, those who had received palliative care for 90 days or more were less likely to have late-life hospitalizations and to visit intensive care units or emergency rooms than those who sought care later.

The reduced hospital use also saved thousands of dollars per patient, a bonus other studies have documented.

“If people aren’t in excruciating pain at 3 a.m., they don’t call 911 and go to the emergency room,” Dr. Meier pointed out.

Yet palliative care remains underused. Even at the well-established U.C.S.F. cancer center, which began offering the service in 2005, only a third of patients in the study had received a palliative care referral.

“We hear this all the time: ‘They’re not ready for palliative care,’ as if it’s a stage people have to accept, as opposed to something that should be a routine part of care,” said Dr. Eric Widera, who practices the specialty at the university.

In fact, the cancer center at U.C.S.F. adopted a euphemistic name for its palliative team: “the symptom management service.”

“We deliberately called it that because of how much ignorance or confusion or even bias there was against the term ‘palliative care,’” said Dr. Michael Rabow, director of the service and senior author of the new study.

Although 40 percent of their palliative care patients can expect to be cured, “there clearly still are both patients and oncologists who have an inappropriate association in their minds,” he said. “They still associate palliative care with giving up.”

To the contrary, palliative care can help patients live fully, regardless of their prognoses. Consider Herman Storey, a 71-year-old San Franciscan, an Air Force veteran, a retired retail buyer and manager, a patient who feels quite well despite a diagnosis of inoperable liver cancer.

His oncologist at the San Francisco V.A. Medical Center — the Department of Veterans Affairs has been a leader in this specialty — referred him to the palliative care service last fall when Mr. Storey said he didn’t intend to pursue chemotherapy.

“They wanted me to reconsider,” Mr. Storey said, “but I don’t want to get sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Chemotherapy for a previous bout of cancer had helped him survive for three years; it had also made him very ill.

Dr. Barbara Drye, medical director of outpatient palliative care at the cancer center, walked Mr. Storey through his options. The suggested chemo might extend his life by several months, she explained. It would also take a toll.

“It can cause not only nausea and diarrhea, but it affects your taste,” she said. “Food tastes like cardboard. Fatigue can markedly decrease the amount of activity someone can do.”

This time, Mr. Storey decided against treatment. A skilled cook, proud of the duck confit dinner he served guests at Christmas, he wants to continue to enjoy cooking and dining out with friends.

Besides, he has plans: In May, he expects to visit Paris for the 11th time, to mark his 72nd birthday.

Dr. Drye, who helped Mr. Storey complete his advance directives, will arrange for home or inpatient hospice care when he needs it. Until then, she sees him monthly.

She has gently suggested that he take his trip a bit earlier; he has declined. “I feel great,” he told me.

So this is also life with palliative care: Mr. Storey and a companion have rented an apartment near the Place des Vosges. A Parisian friend will throw a dinner party for him, as usual. And he’ll eat at that little Alsatian restaurant where they always remember him.

Complete Article HERE!