IT IS a common refrain from doctors doing the ward rounds in the intensive care unit of any major hospital: ”Please don’t ever let this happen to me.”

Most often the words are uttered at hand-over time when the day-shift doctors brief the evening-shift doctors at the foot of an elderly patient.

Most often the words are uttered at hand-over time when the day-shift doctors brief the evening-shift doctors at the foot of an elderly patient.

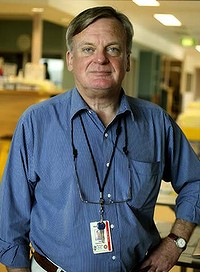

”He might be 80 years old, severe dementia, type two diabetes, previous strokes and a bit of renal failure, and now he’s fallen in the nursing home and suffered a head injury,” says Ken Hillman, professor of intensive care at the University of NSW, ”and the family wants him continued on life support hoping for a miracle.”

Advertisement: Story continues below

There might be six specialists, eight junior doctors and when one finds the courage to say the words, ”We’ll all nod,” says Professor Hillman.

Professor Hillman believes many doctors would not put themselves through ”the same hell we often put other patients through”.

Professor Hillman is a speaker at a conference at NSW Parliament House next week on living well and dying well. The conference is organised by the non-profit organisation LifeCircle which helps people caring for loved ones at the end of their life. ”We support people having a good life right to the end with the conversations that will benefit the person dying and those they love,” said Brynnie Goodwill, the chief executive of LifeCircle.

With daily reports of miracle cures and medical breakthroughs, many people with advanced life-threatening cancers and other terminal illnesses pursue every possible treatment, no matter how gruelling, in the hope of extending life.

But do doctors choose the same path for themselves? The silence around doctors’ views was shattered earlier this year when Ken Murray, retired clinical assistant professor of family medicine at the University of Southern California, wrote in The Wall Street Journal that ”what’s unusual about [doctors] is not how much treatment they get … but how little.” He said doctors did not want to die any more than anyone else did. ”But they usually have talked about the limits of modern medicine with their families. They want to make sure that, when the time comes, no heroic measures are taken.”

Medical scepticism about life-saving interventions was revealed in a 1996 German poll where about half the specialists admitted they would not undergo the operations they recommended to their patients. A study last year, published in Archives of Internal Medicine, showed doctors often advised patients to opt for treatment they would not choose for themselves.

For example, asked to consider treatments for colon cancer, 38 per cent of doctors chose the option for themselves that had a low rate of side effects but higher risk of death (over an option with a high rate of side effects but lower risk of death). But only 24 per cent recommended this option for their patients.

Martin Tattersall, the professor of cancer medicine at the University of Sydney, said: ”I suspect very few doctors would opt for second or third line chemo therapy; my suspicion is that doctors are more likely to prescribe futile therapy than accept it. They’re aware of the statistics. The fact we’re not invincible is something doctors are reminded of every day of their practice and it probably slightly colours their attitude to fighting death as opposed to accepting it.”

Dr Rodney Syme, the author of A Good Death, said his father, a surgeon, when diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, refused surgery to relieve his jaundice even though he had performed the surgery on others many times. ”He didn’t believe there was enough merit in it,” Dr Syme said.

But Richard Chye, the director of palliative care at Sacred Heart, part of St Vincent’s Hospital, said doctors were distributed along the same spectrum as everyone else. ”I’ve known doctors to continue treatment right up until the end,” he said. ”It’s very much about their age group and attitude.”

Professor Hillman said 70 per cent of Australians said they wanted to die at home but 70 per cent died in hospitals.

Complete Article HERE!