By Marcel G.M. Olde Rikkert

It was New Year’s Eve, and my wife and I were visiting my father in his long-term care apartment. He had been cautiously wandering around, waiting for a visit, when we arrived, something he’d been doing since my mom had died a year ago. He looked frail. The “surprise question” occurred to me: Would I be surprised if he passed away in the next year?

No. I wouldn’t.

After we’d spent some time together, I asked his wishes for the coming year.

“I don’t know,” he replied. “I’m 101 years old. I was married nearly 70 years and have finished my life. Marcel, I am very much afraid of dying. Will you ensure that I don’t suffer and that dying won’t take too long?”

I promised him I would try.

The second week of January, I received a call that my father had fallen and was in pain. He had no fracture, but he insisted he did not want to get up anymore. I drove the 120 km to his home, thinking about all of the possible scenarios. My first thought was to get him on his feet again, with enough analgesics to overcome his fear of falling. As a geriatricianson, I had always tried to keep my parents active and felt proud that they had enjoyed so many years together this way.

But would such encouragement fit the situation my dad was in now? He’d asked me to make sure dying didn’t take too long. Was it already time to consider death by palliative sedation? I felt uncertain. To qualify, he needed a symptom that could not otherwise be helped, and death had to be expected within two weeks.

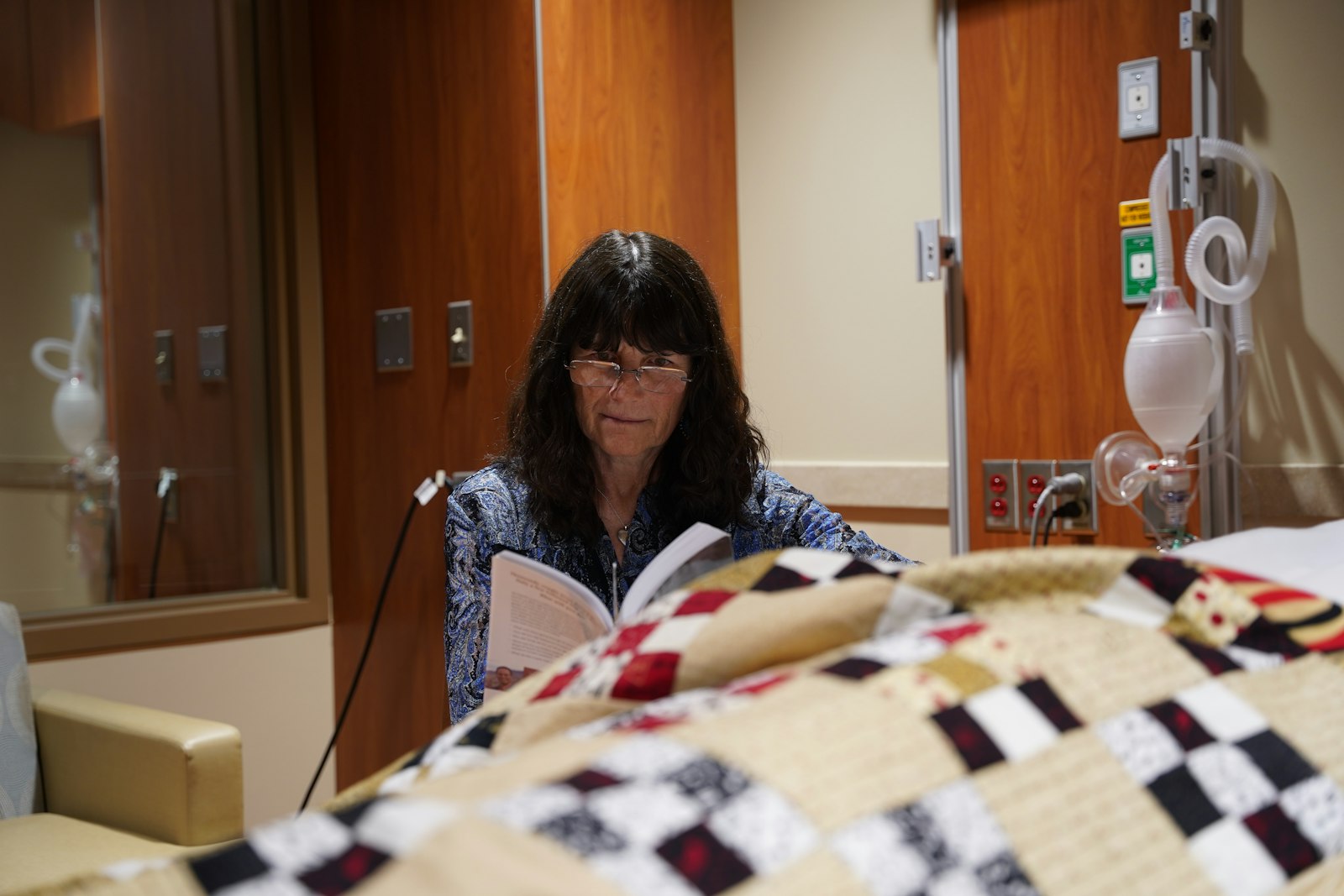

When I arrived at his bedside, he repeated, “I don’t want to get up anymore,” and again, he asked me to help alleviate his fear of dying. I had to honour his heartbreaking request for a peaceful death. With a leaden soul, I went to the doctor on call — luckily his own physician — and asked for his assistance in ensuring a peaceful death. We discussed all options, acknowledging my father’s increasing frailty, despair and anxiety, and we agreed to start acute palliative sedation with midazolam, adding morphine according to the Dutch national protocol. I watched as the doctor prepared the equipment, feeling reassured by his calm professional acts.

My father could not understand the plan himself, but after an hour or so he woke for a few seconds and, with a frail smile, said goodbye to my sisters and me. We made a schedule for staying with him and I took the first turn. I sat next to him for two hours, and just after his second dose of morphine, he stopped breathing and passed peacefully away, just as he had wished. Sadness and relief turned to warm gratitude in my heart. Life had given us a sensitive and wise physician who enabled us to overcome what my dad and I had feared most.

***

In December of the same year, my 86-year-old father-in-law asked me to come to Antwerp and talk to him about the options for assisted dying. He had metastatic prostate cancer and had not recovered over six weeks of hospital care. He was bedridden with a toe infection and painful pressure sores. My reflex, again, was to involve geriatricians and try to get him on his feet. However, my father-in-law, an engineer by profession, had decided it was time to turn off his engine after losing hope for sufficient recovery. My wife and I explained to him what medical assistance in dying and palliative sedation could look like, as both are allowed under certain conditions in Belgium.

Without hesitation, he chose medical assistance in dying. He was very satisfied with his life, having experienced war, liberation, marriage, births, retirement and nice family holidays. In line with his story of life, he did not want to deteriorate further and end his life in pain and misery. We kept silent while he wrote his last will, then thanked us for everything and suggested we should now watch the Belgium versus Morocco World Cup soccer match.

When the game ended, saying goodbye was hard. We looked into his eyes, still bright, and shook his hands, still strong. We knew it was the last time. But his calm smile wordlessly assured me it was time to turn off my own geriatrician’s inclination to pursue mobility and functional improvement. Death was made possible within a week, and after ensuring that all requirements were met and speaking to each family member, his oncologist carried out the procedure carefully in the presence of his children.

***

Just two weeks later, our Spanish water dog, Ticho, made me reflect again on what’s needed most at the end of a long life. For 16 years, Ticho had been my much-loved companion and daily running mate. I had begun to dream he might become the world’s oldest water dog. However, his sad eyes now showed me that his life’s end was close, also evidenced by having nearly all possible geriatric syndromes: slow gait, repeated falls, sarcopenia, cataract, dementia, intermittent incontinence and heart failure.

Still, he came with me on short walks until, one day, he became short of breath, started whimpering and did not want me to leave him alone. Patting calmed him a bit, but I realized we needed to help him die peacefully instead of trying to mobilize him again. Though not comparable to the last days of my dad and father-in-law, there were echoes.

Our three adult kids rightly arranged a family meeting, as Ticho was their sweet teddy bear. We agreed to consult a veterinarian and ask for help with a good farewell. Next morning, the vet agreed with assisting dying. She said Ticho was the oldest dog she had seen so far, and she reassured us that it was the best decision we could make. Again, I felt very thankful for this professional and compassionate help. Ticho died peacefully after sleep induction and, together, my son and I buried him in our garden.

***

Strangely, although death in old age is as natural as birth is for babies, pediatricians seem much more involved in deliveries than geriatricians are in dying. These three encounters with death in my life made me feel I had fallen short so far as a doctor, having undervalued assisting dying at old age. How to guide people to a better end of life was largely left out of my training as a geriatrician. Like pediatricians, geriatricians prefer to embrace life. In geriatric practice and research, we tend to reach for the holy grail of recovery by improving functional performance and autonomy to enhance well-being for frail older people, rather than focusing on facilitating their well-being over their last days. In this tradition, I practised hospital-based comprehensive geriatric assessment and integrated care management, as this had proven effective in giving older people a better chance of discharge to their own homes.

In my research, I had steered a straight line toward longevity and improving autonomy, in accordance with the dominant culture in society and medicine. I had excluded older people with short life expectancies from our intervention trials and did not adapt outcomes to this stage of life. Even for our recently updated Dutch handbook on geriatrics, we did not describe death or dying in any detail. I served many older people in their last days and hours, but did so with limited experience, few professional guidelines and little legal leeway.

Now, having been helped so compassionately with the deaths of three beings close to me, I realize how rewarding it can be to switch clinical gears from recovery-directed management to dying well, and to do so just in time. Older people can show and tell us when they arrive at this turning point and are ready for ending life. I hope other physicians will realize, as I have, how important it is to allow death into a conversation, even a care plan, and to be adequately trained to do so. Perhaps we also need our own turning points as physicians to get ready for the delicate responsibility of compassionate and professional assistance in personalizing good death in old age.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!