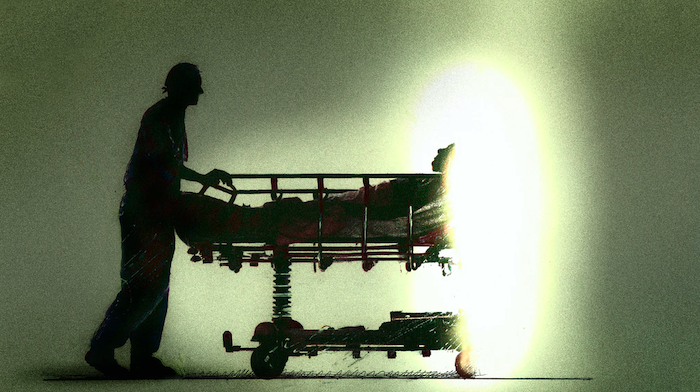

Like so many people, I have spent much of this pandemic grappling with grief. I’ve lost people I love, and even now, people I care about are ill. Even if you haven’t personally lost someone, you’re likely tapped into the collective sense of mourning. It’s hard to know how to comfort people who are dying or the people who love them under any circumstances, but when you can’t be together, it makes it even harder.

That’s where death doulas step in. In case you aren’t familiar with the term, a death doula is like an end of life midwife. They help dying people by guiding them and their families through the dying process. They help people plan out their death experiences. They can aid in navigating the practical parts — like wills and funeral planning, and also the emotional aspects — like helping people figure out what kind of rituals will make grieving cathartic.

Many of the usual ways that dying people and those who love them deal with death — deathbed visits, meetings with spiritual advisors, grief counseling — are not available to us right now. We may not get to have much, if any, contact with a person dying of coronavirus. In this pandemic of mass uncertainty, death doulas can help us through the grieving process.

“Doulas are professionals who provide support and guidance to individuals and their families during transformative life changes,” Ashley Johnson, an Atlanta-based death doula and founder of Loyal Hands, a service that matches people with end-of-life doulas, tells me. These doulas can train family members in some of the practical aspects of caregiving, help people create support plans, and counsel those who are dying and the people who love them, Johnson tells me.

Death doulas are also educators, in a way. Most of us spend a lot of time trying not to think about death, and we aren’t well-versed with the death process. Most of us aren’t even aware that death is a process that can be charted. Death doulas help folks get familiar with the normal and natural stages of dying, Johnson tells me. In the terrifying and confounding moments when grieving people are wondering what happens next and how they can deal with it with dignity, death doulas can step in to fill in the blanks.

There’s kind of a new-age, woo-woo stigma surrounding the work that death doulas do. They aren’t priests and they aren’t psychiatrists, so their professional world is kind of murky spiritual-ish/life coach-ish territory. But some psychologists do think that death doulas can play an important role in helping people cope with grief. “A doula could help people figure out how they want to mourn,” says Aimee Daramus, a Chicago-based psychotherapist.

Daramus adds that people should be mindful that many doulas aren’t trained therapists, but because they are familiar with managing grief so they are generally able to tell when a clinical professional is necessary. For people who are spiritually inclined, but not formally religious, this middle ground can be a comfortable place to mourn without devolving into either over-medicalized melancholy or eccentric science-shunning spiritualism.

“A doula should be able to recognize when someone’s thinking or behavior is starting to go beyond the normal range of mourning experiences.” In this way, death doulas can be a touchstone for figuring out if a person is having a healthy grief response or if they may benefit from another type of help. There is no one right way to grieve, of course, but some people can sink into depression if they don’t process their grief as it’s playing out.

One of the benefits of working with a death doula is that you can shop around to hire someone who fits your needs and understands the cultural specifics of your background. “A professional should work to understand the unique cultural practices relevant to that individual or family,” says Thomas Lindquist, a Pittsburgh-based psychologist and professor at Chatham University. This is especially important, he says, during important life milestones.

A lot of folks in the hospice and funeral industries will likely have a passing knowledge of many kinds of death practices, but you can find a death doula who shares your beliefs, or who literally speaks your own language. Grieving, while it is a universal experience, isn’t generic, and Linquist says that it’s important for a family or person’s religious beliefs to be incorporated into their care plan.

But how can a doula help someone die with dignity if they can’t even be in the same room with them? “As doulas, we have had to get really creative about the ways we meet with people,” says Christy Moe Marek, a death doula in Minneapolis/St. Paul, and an instructor at International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA). Marek says that she has met with the families of dying people on their decks and porches, but that she has had to meet with most dying people via Zoom. It’s not ideal, she says, but adds, “it is opening up such possibilities given the constraints of the pandemic.”

Death doulas are finding new ways to support people. “So much of the way this works right now is in helping both the dying and their loved ones to manage expectations, reframing what they hope for, and to shift focus onto how the ways we are connected whether we are able to be together in person or not,” Marek says.

Marek says that helping people accept the reality of difficult experiences is really the whole point of her work. “During the pandemic, what is actually happening is different than we could possibly imagine and we may not like it. We may actually hate it with our whole being, but it won’t change what is. So we work with that,” Marek says, “And that is what ends up being the mark of a good death.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!