Here’s how a loved one could be there at the end

While the number of new COVID-19 cases in Victoria continues to trend downwards, we’re still seeing a significant number of deaths from the disease.

The ongoing outbreaks in aged care, and the fact community transmission is continuing to occur, mean it’s likely there will be many more deaths to come.

As a result of strict infection control measures restricting hospital visitors, tragically, many people who have died from COVID-19 have died alone. Family members have missed out on the opportunity to provide comfort to the dying person, to sit with them at their bedside, and to say goodbye.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We have cause to consider whether perhaps we could do more to preserve the patient-family connection at the end of life.

Who can visit?

There’s some variation between Victorian health-care facilities in how visitor restrictions are applied. Some allow visitors to enter hospitals for compassionate reasons, such as when a person is dying. But visitors are not permitted for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.

The latest figures show 20 Victorians are in an intensive care unit (ICU) with 13 on a ventilator. This indicates their situation is critical.

Despite hospitals, and particularly ICUs, being adequately prepared and resourced to provide high-level care for people diagnosed with COVID-19, patients will still die.

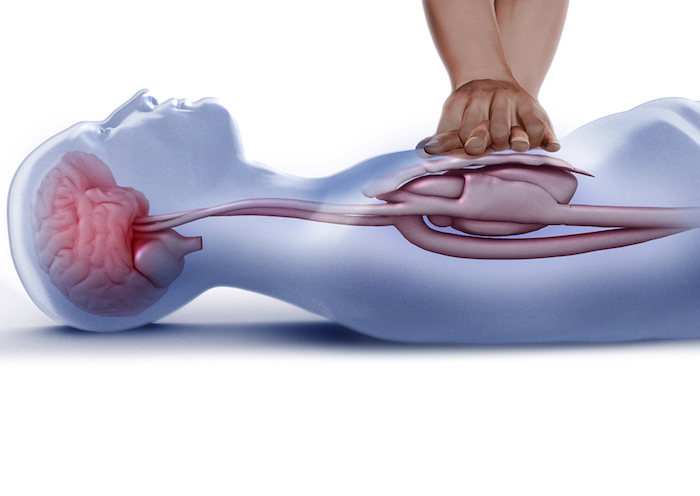

Family-centred care at the end of life in intensive care is a core feature of nursing care. So in the face of this unprecedented global pandemic, we realised we needed to navigate the rules and restrictions associated with infection prevention and control and find a way to allow families to say goodbye.

Our recommendations

We’ve published a set of practice recommendations to guide critical care nurses in facilitating next-of-kin visits to patients dying from COVID-19 in ICUs. The Australian College of Critical Care Nurses and the Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control have jointly endorsed this position statement.

The recommendations are evidence-based, reflecting current infection prevention and control directives, and provide step-by-step instructions for facilitating a family visit.

Some of the key recommendations include:

- family visits should be limited to one person — the next-of-kin — and that person should be well

- the visitor must be able to drive directly to and from the hospital to limit exposure to others

- they should dress in single-layer clothing suitable for hot machine wash after the visit, remove jewellery, and carry as few valuables as possible

- on arrival, staff should prepare the visitor for what they will see when they enter, what they may do, and what they may not do (for example, it would be OK to touch your loved one with a gloved hand)

- a staff member trained in the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) should assist the visitor to put on PPE (a gown, surgical mask, goggles and gloves) and after the visit, to take it off, dispose of it safely and wash their hands

- where possible, the visitor should be given time alone with their loved one, with instructions on how to seek staff assistance if necessary.

We also highlight the importance of intensive care staff ensuring emotional support is provided to the family member during and immediately after the visit.

Tailoring the guidance

It’s too early to know the full impact a loved one’s isolated death during COVID-19 may have on next-of-kin and extended family. But the effect is likely to be profound, extending beyond the immediate grief and complicating the bereavement process.

These recommendations are not meant to be prescriptive, nor can they be applied in every circumstance or intensive care setting.

We encourage intensive care teams to consider what will work for their unit and team. This may include considerations such as:

- whether there are adequate facilities in which the visitor can be briefed and don PPE

- whether social distancing is possible with current unit occupancy and staffing

- whether an appropriately skilled clinician is available to coordinate and manage the family visit

- each patient’s unique clinical and social situation.

Rather than just using a risk-minimisation approach to managing COVID-19, there’s scope for some flexibility and creativity in addressing family needs at the end of life.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!