The answer is yes, but you must qualify and use a Medicare-approved hospice provider.

By Kate Ashford

As you or a loved one nears the end of life due to a terminal illness, hospice care might be a consideration. Hospice is a type of care in which a team of specialized health care professionals make someone who is terminally ill as comfortable as possible during the time they have remaining.

Medicare does cover hospice, but you must meet specific requirements [1]:

- The hospice provider must be Medicare-approved.

- You must be certified terminally ill by a hospice doctor and your doctor (if you have one), meaning you’re expected to live six months or less.

- The hospice care must be for comfort care, not because you’re trying to cure your condition.

- You must sign a statement opting for hospice care over other Medicare benefits to treat your illness. (See an example of this statement here [2].) If you’re thinking about seeking treatment to cure your illness, talk to your doctor — you can stop hospice care at any point.

Hospice care through Medicare generally takes place in your home or a facility where you live, such as a nursing home.

What hospice care is covered?

Hospice care providers care for the “whole person,” meaning they help address physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs [3].

- All items and services needed for pain relief and symptom management.

- Medical, nursing and social services.

- Drugs to manage pain.

- Durable medical equipment for pain relief and managing symptoms.

- Aide and homemaker services.

- Other covered services needed to manage pain and additional symptoms, and spiritual and grief counseling for you and family members.

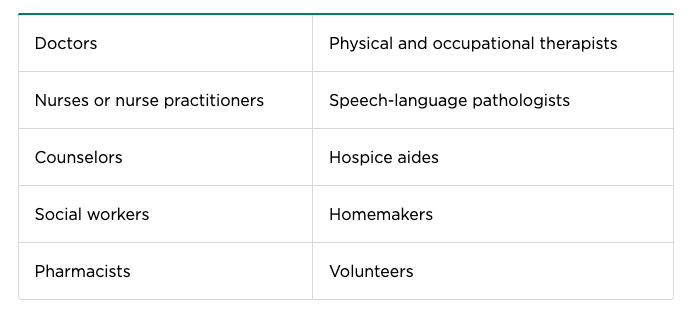

In addition to you and your family members, your hospice care team may include some or all of the following:

You’ll also have the option of a hospice nurse and doctor who are on-call 24/7, for the sole purpose of giving your family support.

What will it cost?

Under Original Medicare, there are no costs for hospice care, although you’ll still pay any Medicare Part A and Medicare Part B premiums.

You’ll pay a copayment of up to $5 for each prescription for outpatient drugs to manage pain and symptoms. You may also pay 5% of the Medicare-approved amount for inpatient respite care — this is care you get in a Medicare-approved facility so your day-to-day caregiver can rest.

What isn’t covered?

Once your hospice benefit has begun, Medicare will not cover any of the following:

- Curative treatment: Any treatment meant to cure your terminal illness or any related conditions.

- Curative drugs: Prescription drugs meant to cure your condition.

- Care from a hospice provider that wasn’t arranged by your hospice medical team. Once you have a hospice provider, you must get care arranged by them. You can still see your primary doctor or nurse practitioner if you’ve picked them to be the attending medical professional that helps manage your care.

- Room and board: If you’re at home or you live in a nursing home or hospice inpatient facility, Medicare will not cover room and board. If your hospice team decides you need a short inpatient or respite care stay, Medicare will cover the costs, although you may owe a small copayment.

- Care received as a hospital outpatient (such as in an ER), as a hospital inpatient or ambulance transport. However, Medicare will cover these services if they’re arranged by your hospice team or they’re not related to your terminal illness.

Starting hospice care

If you have Medicare Advantage, your plan can help you find a local hospice provider.

The hospice benefit is meant to allow you and your family to stay together at home unless you require care at an inpatient facility. If you need inpatient care at a hospital, the arrangements must be made by your hospice provider — otherwise you might be responsible for the costs of your hospital stay [4].

How long can you get hospice care?

If you’ve been in hospice for six months, you can continue to receive hospice care, provided the hospice medical director or hospice doctor reconfirms your terminal illness at a face-to-face meeting.

If you have other health issues that aren’t related to your terminal illness, Medicare will continue to pay for covered benefits, but generally, hospice focuses on comfort care.

Under your hospice benefit, you’re covered for hospice care for two 90-day benefit periods followed by an unlimited number of 60-day benefit periods. At the start of every benefit period after the first, you must be recertified as terminally ill.

What if you’re in a Medicare Advantage plan?

Once your hospice benefit begins, everything you need will be covered by Original Medicare, even if you decide to stay in your Medicare Advantage plan or another Medicare health plan. (You do have to continue paying the premiums.)

If you remain a member of a Medicare Advantage plan, you can use the plan’s network for services that aren’t related to your terminal illness, or you can use other Medicare providers. Your costs will depend on the plan and how you follow the plan’s rules.

Nerdy tip: If you start hospice care after Oct. 1, 2020, you can request a list of items, services and drugs from your hospice provider that they’ve classified as unrelated to your terminal illness and related conditions, including the reasons behind their inclusion on the list. (Find an example of this kind of statement here.)

Can you stop hospice care?

If your condition gets better or goes into remission, you may wish to end hospice care. You can stop hospice care at any point, but you must make it official: You’ll need to sign a form that states the date your care will stop.

Note that you should sign a form of this kind only if you are ending hospice — there are no forms with an end date when you start hospice care.

If you were in a Medicare Advantage plan, you’ll still be a member of that plan after you end hospice and are eligible for coverage from the plan. If you’re a member of Original Medicare, you can continue with Medicare after you end hospice care.

If you have additional questions about your Medicare coverage, visit Medicare.gov or call 1-800-MEDICARE (800-633-4227, TTY: 877-486-2048).

Works cited

- Medicare.gov, “Hospice care,” accessed May 3, 2021.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Hospice,” accessed May 3, 2021.

- Medicare.gov, “Medicare Hospice Benefits,” accessed May 3, 2021.

- Medicare.gov, “How hospice works,” accessed May 3, 2021.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!