— Filmmaker Jack Dunphy on His Slamdance-Premiering Short, Revelations

by Aaron Hunt

Filmmaker Jack Dunphy makes personal films. His shorts Serenity, Chekhov and now Revelations, tell stories from his life with a dash of fiction. He uses construction paper as a base material for his animated films and seemingly does detail work with whatever bachelor-pad rubbish he has on hand. These stop-motion worlds are grubby and handmade; there’s no handsome veneer getting between us and Jack’s emotions, though they’re beautiful in their own right. In Revelations, now streaming as part of the Slamdance Film Festival, he combines animation with video footage and photos from his past to tell the story of his high school relationship with Selene Bennet. To win her attention from the “30-year-old rockstar Jared” and “squidboy,” Jack’s friend Ian, he asks her to star in his movies (footage of which is weaved throughout the film). His plan works, and the two start dating. They’re happy together. Jack learns what it’s like to be happy, for what he thinks is the first time in his life. But then Jared’s mom dies, and he begins to come over while Jack and Selene hang out together. Jared leans on Selene for emotional support and introduces her to oxycodone and morphine, getting her hooked.

In a “last ditch effort” to save their relationship, Jack and Selene do acid together for the first time. This sequence introduces hand-drawn animation, present-day footage from the real world and breaks from the film’s two-dimensional plane. Jack has revelations about his father on his acid trip, realizes he’s a guy like any guy, and that he should probably tell him he loves him more. Revelations, like many of Jack’s films, centers on a relationship with someone in his life, or a particular memory, but reveals itself to be about how these people and events connect to his growing understanding of his father, who passed away.

Even before the credits roll on a Jack Dunphy film, which is often when they confirm their autobiographical nature (assuming you haven’t read about it beforehand), you know the films have no capacity for bullshit, and no reason to pretend or to lie to you. Watching Revelations, I was reminded how rare it is for me to immediately trust a film and what it has to say. The film disarms you from the get-go.

Dunphy talked with me about his DIY animation process, what it feels like when an audience cries in reaction to his films, and the portrayal of death in the movies.

Revelations streams at Slamdance from February 12th to the 25th. Dunphy also has an upcoming podcast of the same name, where he interviews subjects, including addicts and convicts, about addiction and loss, and a feature film in the works called Dear Mo.

Filmmaker: I cried a lot the first and second time I watched Revelations. Have you witnessed someone cry in reaction to your films? What does that mean to you?

Jack Dunphy: I take it as a compliment. Laughter and crying are both involuntary responses, as opposed to applause, so it’s nice to know that something I made can—occasionally—provide people with that kind of emotional release. Once at Sundance, a man started crying while telling me how much my short Chekhov, which also deals with my dad’s death, affected him. His dad had died too. It was an intense and honest moment. All the markers of status that preoccupy us—the acceptance from festival programmers, the Instagram likes—all these lizard-brain things fall away when I realize I’ve really touched someone and maybe even helped them a little. Everything else is bullshit.

Filmmaker: Did you cry at any point in the process of making the film?

Dunphy: The tedium of editing numbs you up pretty good. But when I was animating the acid sequence alone in what used to be my dad’s office, manipulating the cutout photograph of my dad, which hovers above my head in the short, I was listening to a symphonic version of Warren Zevon’s “Keep Me In Your Heart.” It was intense. When you’re emotionally prepared to lean into that kind of pain it can be cathartic and healing. I probably teared up.

Filmmaker: Filmmakers like David Lynch and Paul Schrader encourage others to make their craft their therapy. Lynch thinks going to a therapist would dilute his creativity. Yet neither filmmaker really bares their soul in their work, and their films still exist in a movie world vacuum. They don’t feel therapeutic, but yours do. Are they therapeutic to you?

Dunphy: A movie-world vacuum, that’s such an interesting idea. I know what you mean. Lynch and Herzog both put down psychotherapy, and they’re both full of shit. But I do think making art, for me anyway, is more necessary than actual therapy. It’s more revelatory. It’s what I need to do to survive. The problem is after you make the thing, you’re still alone with the feelings. The girl doesn’t come back, your dad doesn’t come back to life, but the process definitely moves you closer to accepting the events and actions that make up your life.

Filmmaker: How did you come to this tactile style of animation, which we first saw in Serenity? Something about it makes the other elements of actual, live action footage and other styles blend seamlessly.

Dunphy: You’re very kind. It’s not like I worked at being an animator, I kind of stumbled into it. Cutout stop motion seemed really self-explanatory from South Park and Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python cartoons. I liked the collage aspect. Serenity was the first thing I animated—as an adult, anyway. I’ve stuck with stop motion because as you say, it has a delicate, tactile feel. A character in Bluebeard, a Kurt Vonnegut novel, says, “People don’t come to art for perfection, they come to it for imperfection.” So with stop motion, especially the kind of DIY stop motion that I do, you can definitely feel the imperfection.

Filmmaker: Why do you think people gravitate towards imperfection? Why are people turned off by it?

Dunphy: Because they can relate to the vulnerability, the messiness —Daniel Johnston’s original lo-fi tapes are timeless because they’re raw. You’re hearing a kid wrestling through personal pain through an artform he’s navigating as he goes. The hiss in those tapes transports you into his basement—you can almost touch him. Then his squeaky clean, later-in-life studio albums produced by other people—I mean overproduced—are just lame. There’s too much crap getting in the way of the songs. Daniel Johnston is too raw for mainstream audiences. But mainstream audiences aren’t looking for art. They’re looking for entertainment—not that art and entertainment are mutually exclusive. But it’s people who are just looking for entertainment that might have a problem with imperfection. If a Pixar short looked like my shit you’d have crying children and confused parents all over the country demanding their money back.

Filmmaker: Do you animate in your home? What’s the lighting setup look like?

Dunphy: When my co-animator Gus Federici and I were making what became Revelations—which was originally supposed to be part of a feature I’m still making—we were working out of my dad’s office. It was available because he had recently passed. Working in the room he worked in all my life probably had some impact on my mindset. We just used the overhead light in the room. That simplicity helped us.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about the making of the acid-trip sequence, which breaks into all sorts of styles and perspective shifts etc.

Dunphy: I like playing with form and pushing form. I realized a great way to express that moment when you see deeply into someone’s soul, or at least think you do, was to have my girlfriend Selene go from a crude cartoon to a realistic, highly detailed illustration, which Gus made. I can’t draw like that. I couldn’t have done the acid trip or anything else in the film without Gus. His rendering of outer space for the moment that closes out the acid sequence, where I float through space as a literal turd—that background was so surprising and impressive. He just splattered white-out on a black piece of construction paper to make the stars. I was like, “Woah. This fucker’s a savant.”

Filmmaker: To my understanding, you can kind of make these films (the animated and archival ones) on your own. Was it challenging to bring other people into the room?

Dunphy: Roger Miller said songwriting is like having kittens, you just go under the porch and do it yourself. That’s how I approach most of what I do. But occasionally someone like Gus comes along who fits into my little world and elevates everything. We don’t talk about the emotion behind things—we don’t talk much at all. I don’t think we’ve once had a “theoretical” discussion about anything.

Filmmaker: What has the process been like in lockdown?

Dunphy: I hate to say the pandemic was good for me because it was and still is bad for so many people. But it was good for me. The mandatory isolation forced me to stop running with the wrong people and going to the wrong places. I started getting healthy and learned to be alone with myself again. When you’re not scared to be alone with yourself there’s no end to what you can get done.

Filmmaker: Is the work sustainable?

Dunphy: Like financially sustainable? No. You get a check here and there but it’s not a living wage. I have to take on other jobs. It’s funny, the thing you work hardest at, your own work, doesn’t pay shit. But the jobs where you barely have to work at all—like video editing or voiceover work—pay. But it’s not like those gigs grow on trees. There’s a fair amount of luck involved. I’m always grateful for them when I get them.

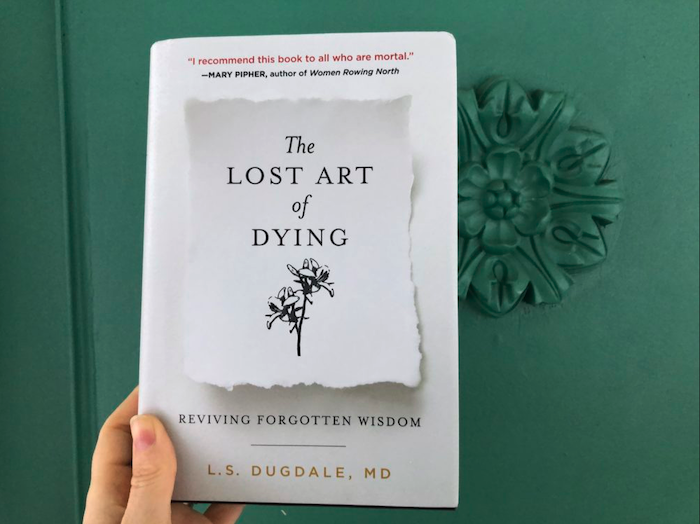

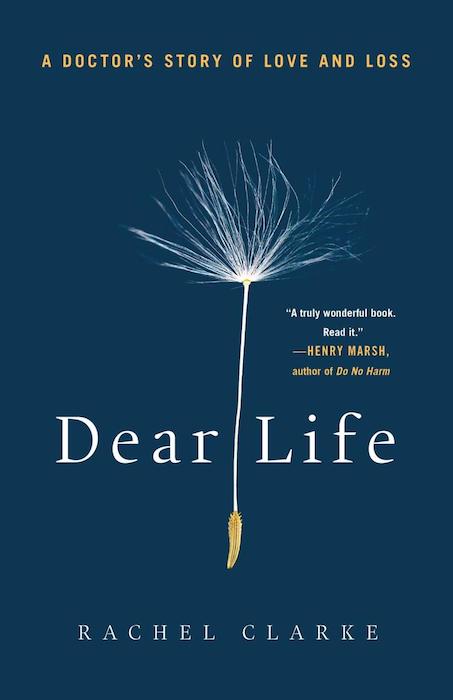

Filmmaker: How do you feel about the general portrayal of death in movies and media? Can you think of an example that resonated? One that didn’t?

Dunphy: Oh, so many movies are disingenuous about it and it pisses me off. The Hollywood version of death and dying, where the dying man gives a great big speech on his deathbed and his children get closure and everything’s wrapped up in a neat bow—that’s not how it goes. It’s like how Hollywood presents love. It creates unrealistic expectations. It’s such a disservice. I thought Michael Haneke’s Amour got it right. Death’s gruesome, let’s not kid ourselves.

Filmmaker: The ending scene, where your dad asks you if you had any revelations during your acid trip, and you think about the loving revelation you had of him during it, but decide not to tell him, gets me everytime.

Dunphy: I’ve been on acid so many times and decided, “I’m gonna write my grandpa a letter and tell him how great he is!” Then you sober up and you never do. Now my grandpa’s gone. If you do a harmful drug like coke, it’s probably best to forget the plans you made on it. That idea for a screenplay you jotted down after your fifth line probably doesn’t need to be written. But with psychedelics—if you do them right—you come up with some good shit. Life shit. Then you make the mistake of saying, “Ha! those crazy drugs. What crazy thoughts I had on those crazy drugs. Okay, back to living my life exactly the way I lived it before I had those great revelations—put the blinders back on, hop back on the hamster wheel.”

Filmmaker: My partner also lost her father but cried less than I did watching Revelations. She said it’s impossible to live in that regret space of “sentiments left unsaid” for someone who lost a parent (or both) without going insane. She felt that the ending might feel more emotional for people who have both their parents because they still have an opportunity to say what they regret not saying, but don’t. They have the privilege of being able to let themselves feel that regret.

Dunphy: I’m sorry for your girlfriend’s loss. And I’m happy you have a girlfriend. I always tell people who haven’t lost a parent: it’s unfathomable until it happens. Then you realize life really does go on. Don’t get me wrong, it will throw you way off balance. But it’s natural. Our parents are supposed to die before we do. There can be relief in finality. Meanwhile, it’s terrible living in fear that you’ll never be able to tell your parents what you really want to tell them before they die. Why are we so emotionally constipated? I don’t know. My grandpa and I never once said we loved each other. If I ever told him I loved him he would probably just break eye contact, hand me a dollar and walk away. It was a generational, Irish thing, I guess. So I figured my way of showing him I loved him was to interview him. He was on the news once and he loved it—some old people like to be reminded that they’ll have a legacy to leave behind. So I was in a perpetual state of anxiety, like, “God, I have to get around to interviewing my grandpa. But not this Thanksgiving, I’m too fucking miserable. Next Thanksgiving. Next Thanksgiving—and so on.” Finally, he literally died on Thanksgiving. And I never interviewed him. So what am I going to do? Dwell on that regret? I already have so many regrets about things I never told my dad and other folks in my life who have shuffled off this mortal coil. So I can’t take on new ones. I’m busy trying to rise above the ones I already have.

Filmmaker: Your films often show real people from your life shockingly unfiltered. Do you prepare them for it? Are there rules?

Dunphy: I mean, legally there are rules. I got sued once. I used to think the way to go about making personal work was to be a bit of a bully and just plow through boundaries and other people’s feelings. I don’t think that way anymore. But no matter how gentle you want to be, if you want to tell a story honestly, or at least in a way that you perceive to be honest, you occasionally have to choose between protecting someone’s feelings and the work. I lost a close friend because I chose the latter. But 90% of the time no one’s pissed about the way I represent them because they see the love. And the way I represent them is not completely unfiltered. I don’t like to give away what’s real and what’s not. It’s not all factual but it’s all true. There are many Selene’s. I’m planning on bracing the one that’s still alive.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!