Coronavirus prompts more people to consider, or revisit, end-of-life care

By Naomi Martin

The coronavirus pandemic has pushed the fact of human mortality to center stage, prompting scores of people, not just doctors, to consider or revisit their end-of-life wishes. Complicating matters, the pandemic has introduced ventilators — a life-support tool seldom discussed outside hospitals before the outbreak — into mainstream Americans’ worries.

Amid talk of hospitals rationing ventilators, some people are updating their living wills or proxies to say that they do want a ventilator to extend their lives, if necessary. Others, largely elderly people and those with serious health conditions, are making it clear that if their odds aren’t great, they wouldn’t want the machine to keep them alive.

“In the two-and-a-half years we’ve existed, we’ve never answered questions on ventilators, but now they’re pretty common,” said Renee Fry, cofounder of Gentreo, which offers low-cost estate planning.

It’s urgent that people clarify their wishes to family now, doctors say, because the coronavirus can progress quickly, making patients suddenly so sick that to stay alive, they must be put in a medically induced coma and on a ventilator.

In that moment, they may not have a chance — or be able — to fully consider the potential consequences such as brain and organ damage, or needing to live bed-bound with a feeding tube.

Most people who contract the coronavirus don’t become seriously ill, and only a small portion require intensive care. However, early data suggest that perhaps 50 percent to as many as 80 percent of coronavirus patients who are placed on ventilators don’t survive.

“The reality is even if we have enough ventilators, that’s not going to save most people,” Dr. Breanne Jacobs, an emergency room doctor and professor at George Washington University School of Medicine who wrote about the issue.

Most elderly people would prefer to pass away at home with family rather than alone in a hospital, she said, so “if they understand a ventilator is not going to miraculously get them back to where they were, a lot of people would probably change their mind about allowing doctors to do intubation.”

The crisis has prodded many people to take up the oft-deferred task of discussing end-of-life goals. Thousands have downloaded a new coronavirus-related guide from The Conversation Project, which helps people broach the uncomfortable topic.

Doctors advise against using medical terms, like ventilator, in documents, because that’s not helpful to clinicians aiming to follow someone’s overarching wishes. Instead, they say, people should focus on big-picture values.

“A lot of people say, ‘I don’t want to be intubated,’ but they mean they don’t want to be intubated for the rest of their lives,” said Suelin Chen, cofounder of Cake, which offers free end-of-life planning services. “If it were just to recover for a few days, they’d want that.”

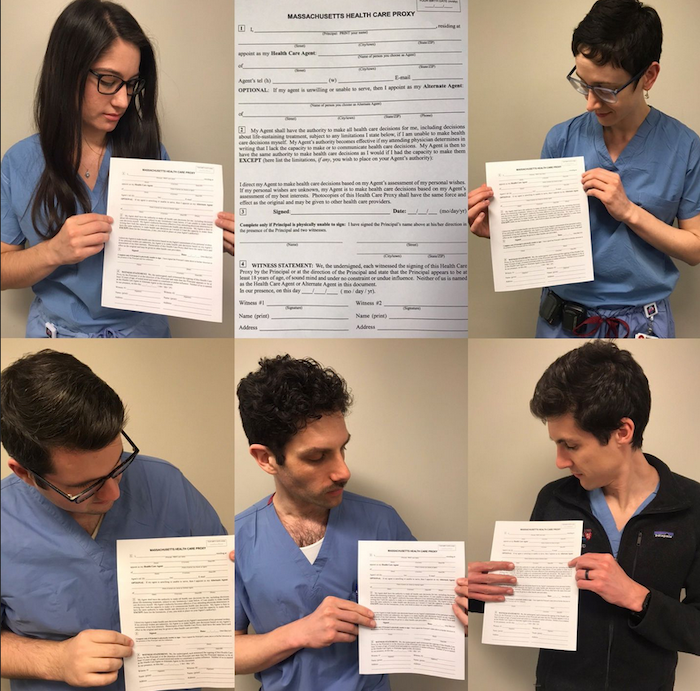

Specialists say everyone over 18 should, at minimum, record their health care proxy, which in Massachusetts requires two witnesses. If that’s impossible during social distancing, people can complete a “trusted decision-maker” form, which is better than nothing.

And they should discuss key questions with their chosen person before an emergency, such as what makes life worth living, how much suffering are they willing to endure, and for what odds of success.

These should be ongoing conversations, as people’s wishes change with age and health status, they said.

“This isn’t just doom and gloom — it’s how do you want to live your life all the way through the end?” said Kate DeBartolo, senior director at The Conversation Project.

The downsides of inaction can be high. Someone may receive procedures they don’t want, as hospitals can be obligated to try to keep someone’s heart beating, regardless of whether their brain is alive. Without clarity, family members may disagree over stopping life support, prompting infighting and guilt. Planning reduces depression in grieving relatives, a 2010 study found.

In some instances, family members may have to go to court to take a loved one off life support.

“With my mom, I always say it was the greatest gift that she gave us,” said Patty Webster, 50, a Conversation Project community engagement leader, whose mother, a hospital chaplain, made her wishes so clear that when she suffered two strokes, her family all agreed when the heart-wrenching time came to stop prolonging her life.

“She had an end-of-life that she wanted,” Webster said. “She had friends and family by her side, laughing and crying, together with her when she took her last breath.”

Amid coronavirus, Webster revisited the topic with her family. She shared an article by a doctor about the damage that ventilation can cause. Afterward, her in-laws, in their 80s, emailed to say they wanted to live to 110, but only if “cognizant, thinking, and communicative,” and likely wouldn’t want ventilators.

Webster and her husband, meanwhile, would be willing to try temporary ventilator treatment for a chance to remain in the lives of their children, 18 and 20, in an active, meaningful way.

People who have started end-of-life planning during the crisis say it offers a measure of control. That doesn’t mean thinking about death gets any easier.

“It’s terrifying to think about when you flat-line, that’s the end,” said Chris Haynes, 48, a South End restaurant publicist who recently crafted his will, but can’t bring himself to envision his end-of-life care. “It just shakes you to your core.”

Pushing past that discomfort can make a huge difference to families and doctors, said Slavin, the MGH resident. In one recent case, he said, a health care proxy for a critically ill coronavirus patient knew that the patient wanted to try a few days on a ventilator. Then, if her condition didn’t improve, she would switch to hospice care.

“It’s hard whenever a patient is dying,” Slavin said, but “it felt like we were doing right by this patient and her family.”

Lately, Slavin has discussed the coronavirus by phone with his primary care patients who have advanced cancer, dementia, or heart failure. He describes the potential harms and low odds they’d face on a ventilator. He recommends that, if infected, they not pursue intensive care. Most patients agreed, he said.

For Slavin personally, the calculus is different. At 33 and healthy, he faces a good chance of recovery if infected and would want to try every option to survive and build a future with his wife.

“At another point in my life,” he said, “I might say, ‘I want a time-limited trial of intensive care, then shift to making comfort the top priority.’ ”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!