— Reflect on your wishes ahead of time to help ensure they will be followed.

By Susan Kreimer

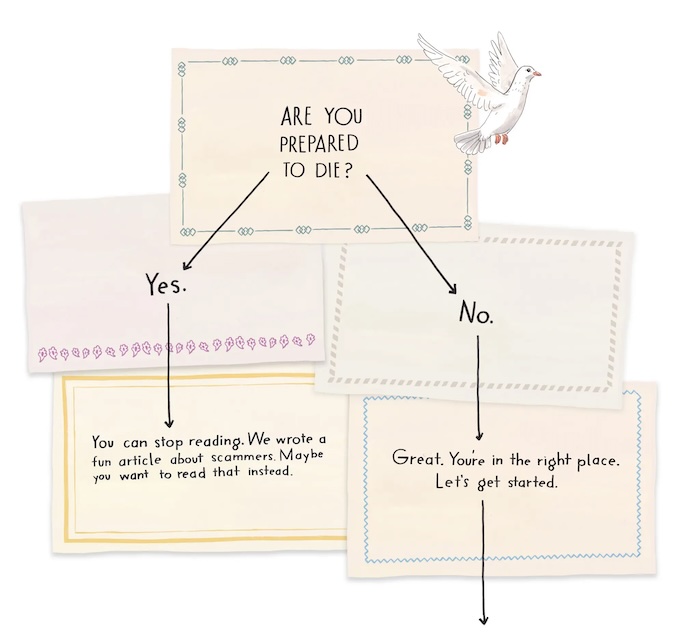

No one can predict exactly how long you will live with cancer, whether you have metastatic stage 4 disease (cancer that has spread to distant organs) or a less advanced stage. No matter where you are in your cancer treatment, end-of-life planning can ease some of the burden on you and your loved ones. If you take time now to reflect on your wishes, you can increase the chances you’ll achieve the outcomes you want.

Soon after any cancer diagnosis is a good time to consider end-of-life planning. Your doctor can answer questions about your prognosis, including what the realistic options are and what those treatments can achieve, says Steven Pantilat, MD, the chief of the division of palliative medicine at the University of California in San Francisco.

Laura Shoemaker, DO, the chair of palliative and supportive care at Cleveland Clinic, adds, “Care planning, ideally, is about planning for the entire trajectory of the illness, including but not limited to end of life.”

This can be done at any time and should be tailored to your needs.

Reflect on Your Values, Priorities, and Wishes

This reflection process can be difficult to initiate, but will be well worth it. It should include talking with your family, caretakers, or even a counselor.

“Each person’s plan will be a reflection of their lives, values, and personal priorities,” says Kate Mahan, LCSW, an oncology social work counselor in the Canopy Cancer Survivorship Center at Memorial Hermann the Woodlands Medical Center in Houston.

“It is often helpful to think of this as a series of discussions instead of a single talk,” she adds. “While we all know that no one lives forever, it is often very challenging to consider our own mortality.”

End-of-life planning allows your healthcare team to understand what matters most to you, says Mohana Karlekar, MD, the section chief of palliative care at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

It’s important to think about expressing your end-of-life wishes in writing if your cancer has progressed, or you’re experiencing more complications from your treatments.

This may be the time to ask yourself where you would prefer to spend your final days — for instance, at home or in a hospice house, says Eric Redard, a chaplain and the director of supportive care at High Pointe House, part of the Tufts Medicine Care at Home network, in Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Do you want to accomplish anything special? Is there a meaningful place for you to visit while you’re still mobile? “The list is endless,” says Redard.

Appoint a Decision-Maker

By communicating openly with your healthcare team, you can make more informed choices about the medical care you want if the time comes when doctors and family members have to make decisions on your behalf.

One of the most important end-of-life decisions for any person with a cancer diagnosis involves selecting someone who will be a voice for you when you can’t speak for yourself.

“Ask yourself, who would I want to make decisions for me? Anyone with cancer could — and should — do that,” says Dr. Pantilat.

Your choice can be enforced through a durable power of attorney for healthcare. It’s a type of advance directive, sometimes called a “living will.” This document names your healthcare proxy, the person who will make health-related decisions for you if you can’t communicate them to your providers.

Write Advance Directives

Outline your wishes in advance directives. The following are decisions you may want to consider including in these documents, says Redard.

- Tube feeding Nutrients and fluids are provided through an IV or via a tube in the stomach. You can choose if, when, and for how long you would like to be nourished this way.

- Pain management It’s helpful for advance directives to include how you want the healthcare team to manage your pain. You can request as much pain-numbing medicine as possible, even if it makes you fall asleep, or just enough to reduce pain while allowing you to remain aware of the people around you.

- Resuscitation and intubation You may decide that a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order is right for you. This is a medical order written by a doctor that informs healthcare providers not to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if your heart stops beating. Similarly, a do-not-intubate (DNI) order tells the healthcare team that you don’t want to be put on a ventilator if your breathing stops.

- Organ and tissue donations You may want to specify that you want to donate your organs, tissues, or both for transplantation. You may be kept on life-sustaining treatment temporarily while they’re removed for donation. To avoid any confusion, consider stating in your advance directive that you are aware of the need for this temporary intervention.

- Visitors You may wish to make it known in advance who will be able to see you and when. This may include a visit from a religious leader. For some people, such a visit can provide a sense of peace.

Even if you write advance directives, it’s a good idea to discuss them with everyone involved in your care. “There is no substitute for meaningful conversations with loved ones and medical providers about one’s care goals and preferences,” says Dr. Shoemaker.

The advance directives can also specify if you would like to receive palliative care.

Choose Palliative Care

“Palliative care provides symptom control and supportive care along the entire disease continuum, from diagnosis of advanced cancer until the end of life,” says David Hui, MD, the director of supportive and palliative care research at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

It treats a range of symptoms and stress issues such as pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression, nausea, loss of appetite, and nutrition.

“We generally advise that patients with advanced cancer gain access to specialist palliative care in a timely manner to help them with their symptom management, quality of life, and decision-making early in the illness trajectory,” says Dr. Hui.

The goal of this approach is to provide an extra layer of support not only for the patient but for loved ones as well, especially family caregivers, according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care. It is appropriate at any age and at any stage of a serious illness, and you can receive it along with curative treatment.

Consider Hospice Care

Hospice care is one branch of palliative care. It delivers medical care for people who are expected to live for six months or less, according to the Hospice Foundation of America.

You may decide to consider hospice when there is a major decline in your physical or mental status, or both, despite medical treatment. Symptoms may include increased pain, significant weight loss, extreme fatigue, shortness of breath, or weakness.

Hospice can help you live with greater comfort if you decide to stop aggressive treatments that may have weakened you physically without curing your cancer or preventing it from spreading. Hospice care does not provide curative therapies or medical intervention that is intended to extend life.

A hospice care team often includes professionals from different disciplines, such as a doctor, nurse, social worker, chaplain, and home health aide. This team can guide you in managing your physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs. They also support family members and other close unpaid caregivers.

Find Comfort at the End of Life

Finally, remember that end-of-life planning isn’t solely about medical care. It’s also a time when you will need emotional support. So, consider mending broken relationships, surrounding yourself with pictures of family and friends, and playing music that soothes your soul.

“People can write letters to loved ones, forgiving them or reconciling,” Redard says.

End-of-life planning is a topic people tend to shy away from, but it removes the burden from those left behind. “Once it’s over,” says Redard, “there’s relief.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!