By Peter Whoriskey

The doctor floated through the intensive care unit, white lab coat flapping, moving from room to room, scanning one chart and then another, often frowning.

Unlike TV dramas, where the victims of car crashes and gun shots populate the ICU, this one at Sentara Norfolk General, as in others in the United States, is more often filled with the wreckage of chronic disease and old age.

Of 10 patients Paul Marik saw that morning, five had end-stage kidney disease, three had chronic respiratory ailments, some had advanced dementia. Some were breathing by virtue of machines; others had feeding tubes; a couple were in wrist restraints to prevent them from pulling off the equipment.

For a man at a highly rated hospital surrounded by the technology of medical miracles, Marik sounded a note of striking skepticism: Patients too often suffer in vain attempts to prolong life, he said, because of the mandate to “do everything.” The urge to deploy every last aggressive medical technique, in other words, was hurting people.

“I think if someone from Mars came and saw some of these people, they would say, what have they done to deserve this punishment?” said Marik, gesturing to the surrounding rooms. “People might say we are prolonging life, but we end up prolonging death.”

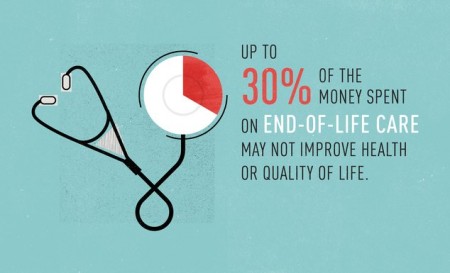

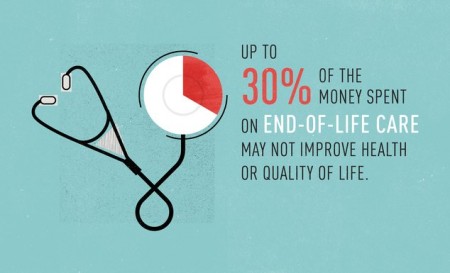

Critics of U.S. health care have long marshaled evidence against the overuse of aggressive end-of-life care, but the idea that many Americans are dying badly — subjected to desperate treatments in ways that are not only expensive but painful and medically futile — has gained currency of late.

Critics of U.S. health care have long marshaled evidence against the overuse of aggressive end-of-life care, but the idea that many Americans are dying badly — subjected to desperate treatments in ways that are not only expensive but painful and medically futile — has gained currency of late.

This fall, a photogenic 29-year-old with brain cancer made the cover of People magazine with the decision to end her life on her own terms. About the same time, Medicare proposed that doctors be paid for discussing with patients their options for treatment — or not — at the end of life. And on the best-sellers lists is “Being Mortal,” a surgeon’s critique of the way the United States handles decline and death.

In it, author Atul Gawande warns, among other things, that “spending one’s final days in an ICU because of terminal illness is for most people a kind of failure.”

Marik’s long-standing argument, which is notable in part for coming from an ICU doctor, is this: The nation has double or triple as many ICU beds per capita as other Western nations, it spends inordinate amounts of money in the last months of life, and worst of all, this kind of care isn’t what patients want.

His doubts about end-of-life care appear to be widely shared among his ICU colleagues.

A 2013 survey conducted in one academic medical center, for example, found that critical care clinicians believed that 11 percent of their patients received care that was futile; another 9 percent received care that was probably futile, it said.

Marik blames, in part, people’s unwillingness to face up to the inevitable.

“Americans not only don’t want to die, they are unwilling to accept the reality of death,” said Marik, who is also a professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School and chief of critical medicine at the school. “Unfortunately, old people get diseases and die.”

It pays to provide treatment

The remedy lies, in part, with hospices, which are hired to take care of patients after they opt out of aggressive end-of-life care.

Amid rapid growth, that industry has been marked by infrequent government inspections and, in places, lapses in quality. But when the service has been properly provided, families sometimes describe it as a godsend, and experts say hospices serve a critical role in the U.S. health system.

A number of factors, economic and personal, keep many patients from enrolling in hospice care, however.

For starters, it pays to keep dying patients undergoing more treatment, according to experts.

“Financial incentives built into the programs that most often serve people with advanced serious illnesses — Medicare and Medicaid — encourage providers to render more services and more intensive services than are necessary or beneficial,” according to Dying in America, a massive report issued in September by the Institute of Medicine.

But strains at a more personal level also keep patients in treatment.

Doctors are reluctant to disappoint a patient with the grim truth, and knowingly or not, keep false hopes alive. Families meanwhile sometimes overestimate the power of modern medicine.

Take, for example, the use of CPR, the technique that can restart a heart, but which, particularly in the elderly, can result in broken ribs, and even if successful in reviving a patient, may lead to a much-diminished quality of life.

Take, for example, the use of CPR, the technique that can restart a heart, but which, particularly in the elderly, can result in broken ribs, and even if successful in reviving a patient, may lead to a much-diminished quality of life.

“Have you ever seen it done on television?” Marik asks, rolling down a corridor with a class of students behind him. “They all wake up right away. But in real life, only about 5 to 10 percent of people — if they’re over 70 — leave the hospital alive.”

Indeed, a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine an analysis of popular shows like “ER,” showed that two-thirds treated by CPR survived until discharge.

“When CPR became widespread in the ’60s, it wasn’t considered ethical to perform it on people who are unlikely to recover,” Marik said. “Now it’s done all the time, regardless of the consequences.”

‘A warehouse for the dying’

Marik has been making his argument in published papers at least as far back as 2006, and his criticism echoes others in the field. An ICU doctor in Gawande’s book, for example, complains that she is running “a warehouse for the dying.”

“We’re kind of powerless to change the system — this is what society expects of us and what we are legally required to do,” Marik said. “But many clinicians are frustrated.”

Nurses, who interact with patients more, may be just as adamant about the issue. They see patients grimacing as they clean wounds around tubes into the lungs or stomach; they see confused patients trying to remove breathing equipment; they treat the bed sores of patients immobilized for long periods.

“There are cases where you honestly feel like you are just causing more harm or pain to the patient and you wonder if their family really understands what’s going on,” said Karen Richendollar, a nurse at the intensive care unit at Sentara Leigh Hospital here.

Surveys of intensive care nurses at 14 ICUs in Virginia, published in 2007 in the journal Critical Care Medicine, found that the leading cause of moral distress arises from the pressure to continue aggressive treatment in cases where the nurses do not think such treatment is warranted.

“The distress comes when there is no hope that whatever we are going to do will provide any different outcome,” said Becky Devlin, the supervisor in the ICU here. “The patient is going to die anyway, and we are just prolonging things. That’s where the distress comes in.”

For example, Devlin and Richendollar said, a woman then in their care was more than 90 years old, with blood pressure and severe kidney problems as well as severe dementia. She was being fed through a tube and had a urinary catheter.

Most imposingly, the woman was breathing via a ventilator, and to prevent her from removing the tube that had been inserted into her mouth and down her throat, restraints tied her hands to the sides of the bed.

“No one can be comfortable with all of that,” Devlin said. “Some of the family members are against further treatment, but there are others that make the decisions and they want to keep going.”

End-of-life planning key

One key way to avoid unwanted treatment, according to experts, is to solicit a person’s preferences for end-of-life care before a crisis arrives.

Toward that end, Sentara, which was ranked this year atop the “Best Hospitals in Virginia” by U.S. News & World Report, joined a coalition of hospitals and agencies on aging that in November launched a program to promote end-of-life planning in the Norfolk and Virginia Beach area. It has set up a Web site, asyouwishvirginia.org.

The program hopes to inspire people to write down their wishes and appoint a health-care advocate to speak for them if they can no longer do so. Organizers will blanket the region’s religious group and elderly care organizations to encourage people to make end-of-life plans.

“Unfortunately when these situations [in the ICU] come up, families will say, ‘Doc, what should I do?’ But that’s not something that doctors can really answer,” said David Murray, director of the group, known as the Advance Care Planning Coalition of Eastern Virginia. “We need to hear from the patients or their representatives — earlier than we do now.”

Take, for example, one of Marik’s patients, a 72-year-old woman who’d come into the emergency room last month after her family found her confused.

Living at home, she’d long been beset by multiple health woes, mainly congestive heart failure and respiratory problems and bipolar disorder. Given her fragility, it would have been natural to have elicited her end-of-life wishes.

No one did, however, and at the hospital last month the hospital staff and the family spent several anguishing days discussing how best to proceed with her care.

Her labored breathing — her inability to draw in oxygen — was the central problem for the doctors. As she struggled for air, the carbon dioxide levels in her blood rose to dangerous levels. She grew anxious as a result, and this only worsened her breathing.

She was moved to the ICU.

The staff placed an oxygen mask called a biPAP around her head, fitting it snugly around her mouth and nose. The device forces oxygen from a hose into the nose and mouth, but it is often uncomfortable.

As a result, the patient was at risk of removing it. So in addition to being sedated, her hands were restrained — tied by cloth belts to the sides of her bed.

She could be heard that Monday calling out, at times, unintelligibly.

“Take me, Jesus,” she shouted at one point.

She wasn’t the only one bothered by the arrangement.

“The nurses and I were really uncomfortable — this poor little old lady,” Marik said. “She was an elderly demented lady with chronic end-stage lung disease. . . . We were subjecting her to a lot of pain and indignity with very little potential for gain. We shouldn’t be forced into that kind of situation, but we often are.”

By Wednesday, the hospital’s palliative medicine team met with family members, and in the coming days, the patient’s sister and daughter decided to forgo aggressive treatment and opt for measures meant primarily to keep her comfortable.

The uncomfortable mask and the wrist restraints came off. Her vitamins and cholesterol drugs were stopped. She was given medicine for her anxiety, which family members said had been a long-running source of trouble for the patient.

The patient was also prescribed morphine, a drug sometimes avoided until the end of life, but one that relieves pain and calms breathing. Nurses were instructed to give her morphine when her breaths exceeded 20 per minute.

Placed under hospice care, she was sent to a nursing home the next Monday.

There, the patient seemed to rally, regaining the ability to interact with family members. The color returned to her face. She even said she was enjoying music they brought in.

A few days later, after the family had the chance to call in distant relatives, she died.

Marissa C. Galicia-Castillo, a doctor in the hospital’s palliative medicine department, said it is common for patients to die in the ICU hooked up to machines.

“Fortunately . . . [this patient] was able to get out of the hospital into a more home-like environment, enjoy some familiar comforts, visiting and talking with loved ones before the natural end of her life,” she said.

But it wasn’t without the torment before the family decided that the aggressive measures may be introducing more pain than relief. Sometimes frail elderly patients languish weeks or months before family members opt for the comfort measures. Sometimes they die hooked up to multiple machines. In this sense, this patient constituted a success.

“We all knew she was dying, and that was the tragedy,” Marik said. “We knew we were just prolonging her death.”

Complete Article HERE!