[O]ncology nurses are in the perfect position to implement ideal care for their patients via the use of the family meeting in palliative and end-of-life care. This type of meeting provides an opportunity to coordinate the responsibilities of caregivers and clinicians with patient needs, according to a study by Myra Glajchen, DSW, director of medical education, MJHS Institute for Innovation in Palliative Care, New York, and Anna Goehring, MD, palliative care physician, MJHS Hospice and Palliative Care, New York.1

Oncology nurses usually spend more time with patients than other staff and are able to answer patients’ questions about their medical conditions and discuss end-of-life issues with patients when they are ready to do so. They are also in a good position to evaluate caregivers’ condition and determine how involved caregivers want to be in helping patients make crucial decisions. These decisions are often difficult, yet Ms Glajchen and Dr Goehring write that end-of-life communication skills are not emphasized in the nursing literature.1 They note that the role of the oncology nurse in family meetings is not clear and that there has been little guidance on evaluating and managing caregiver distress.

Family caregivers have their own obligations but often bear heavy, difficult caregiving responsibilities in addition to handling their own personal concerns. Nurses can evaluate the extent to which their caregiving burdens go beyond their skills to cope and provide what their ill family member needs. Oncology nurses also are responsible for assessing the strength of the relationship between patients and their caregivers. A satisfying relationship correlates with a better commitment on the part of the caregiver, although this must be balanced with other activities to avoid caregiving becoming fraught and burdensome.

There must also be a balance with other family members; the researchers stress that a diagnosis of cancer for one family member affects the entire family. Caregivers for patients who are being actively treated for disease are in better physical and emotional health than caregivers for patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care. Oncology nurses should use family meetings to evaluate and structure caregiving situations for patients, caregivers, and their families.

The Meeting

There are a number of reasons for healthcare teams to request a family meeting. Often such meetings are about a decline in a patient’s medical condition or another change in the patient’s prognosis that requires making decisions about new treatments and different options for advance care planning. Meetings may also be called for specific purposes such as completing living wills, do not resuscitate (DNR) and do not intubate (DNI) orders, or to discuss mechanical ventilation, artificial hydration, and nutrition. The nurse’s role is key in these decisions. Oncology nurses are qualified to understand medical information, which they can easily interpret for patients and their families at these meetings. For this reason, it is important for oncology nurses to obtain and review all updated information from the patients’ clinicians prior to the meeting.

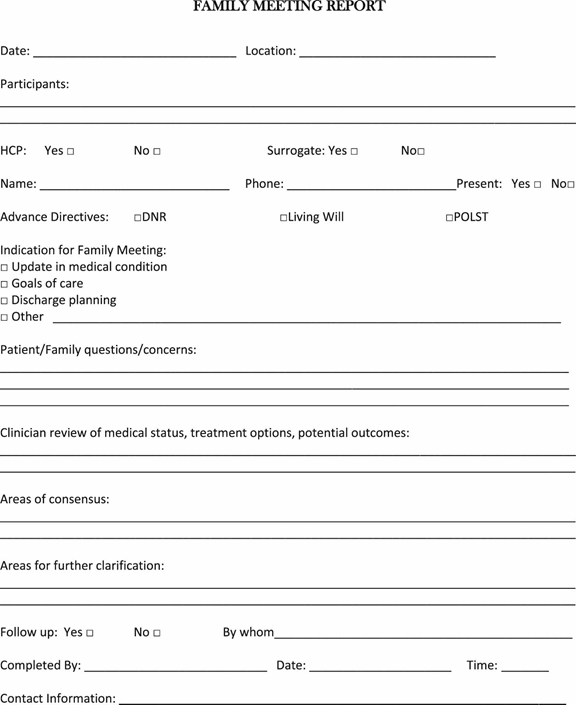

With the oncology nurse at the meeting, other clinicians only need to attend if doing serves a specific purpose.1 However, the participation of involved staff from other disciplines concerned with the patient’s care is helpful. Caregivers the healthcare team or patient wants to invite should attend the meeting, although the researchers caution there should be more caregivers than staff present so as not to overwhelm the family at this difficult time. The care team leader should explain why the meeting was called, provide a clear agenda, and should request all attendees to mute their cell phones and pagers during the meeting. A member of the healthcare team should take notes; the investigators suggested using the Family Meeting Report (Figure 1) and documenting the meeting in the electronic medical record.1

A family meeting takes time; at least an hour for preparation, an hour for the actual meeting, and half an hour to an hour for follow-up is required.1 Despite the work-intensive nature of a palliative care family meeting, the oncology nurse can be a true asset, lowering stress and offering information, realistic hope, supportive care, and comfort to patients, caregivers, and other family members.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!