I didn’t think I’d ever get over the loss of my best friend. Then her daughter came to live with me.

By Gayle Abrams

“Will you accept a new tenant and a puppy?” Ceece texted.

A pretty, smart blonde with a lean, athletic build and a degree in finance, Ceece was the kind of 23-year-old you might hate, since she seemed a little too blessed. Unless you knew the truth.

“Why does the dog need to come?” my husband asked.

“It’s a therapy dog,” I explained. “She got him when Barb died.”

Barb, Ceece’s mom, was my best friend. We met when I was Ceece’s age, working in the publicity department of Bantam Books.

It was the worst time of my life. My father had gone to jail, I was sick with an eating disorder and I’d just lost my mom. I was cold and angry and a liar. Most people would have given up on me. Not Barb. At 6 feet tall, she towered over my 5-foot-2 self, fixed her piercing blue eyes on my hazel ones, and told me she really wanted to be my friend, but there were certain rules I had to follow for that to happen. The main one was I had to always tell her the truth.

For almost three decades after that, while she rose in the publishing world in New York and I built a TV career in Los Angeles, we maintained a long-distance friendship based on this pledge of honesty and trust. We could and did tell each other everything, first writing epic letters, then epic emails. My husband once walked in and stared at the pages of writing on my screen and asked if I was writing a screenplay. “No,” I said. “It’s a letter to Barb.”

We ended up celebrating all our monumental milestones together. We got married the same year and joked that we had married the same man. Both our husbands shared an unflappable temperament and, weirdly, both were managers at consumer banks. We bought similar first houses: Barb’s was an adorable 19th-century farmhouse, mine an adorable 1920s Spanish style.

Then we both bought the same second house, newer and in a more kid-friendly location, when the first one turned out to be totally impractical. We both got pregnant and had a baby the same year. We both ended up having two kids, a boy and a girl, and we would both tell you we couldn’t have survived the dark days when they were little without our amazing “Super Dad” men. Whatever it was we were going through, we were there for each other, and it helped that so often we were going through the same things. But if I had to name the greatest thing Barb gave me, it was that she believed in me, even when I couldn’t believe in myself.

In Her Words: Where women rule the headlines.

Then one day she was diagnosed with terminal cancer and given three months to a year to live. When she made it past one year, I thought we were home free. Until suddenly, she was gone. For months after, I’d wake up in the middle of the night sobbing. I’d lost my oar and my rudder, the person who had taught me unconditional love.

In February 2019, my daughter was in college, my son had just moved out, and I was mere days into my new life as an empty-nester when Ceece texted. She’d gotten a job offer in Los Angeles. Could she stay with us? Of course I said yes.

Weeks later, after she’d spent $1,500 to ship her car, all her stuff and a giant 10-foot cactus out West, she arrived to find out the position she’d been offered was not guaranteed. The woman who hired her said her boss wanted two candidates to choose from.

“What if I don’t get the job?” she asked me, her eyes blinking back terror.

If I told you she didn’t get the job, the cactus arrived brown and droopy and the groomer found a lump under her dog’s fur, maybe you’d think I was being dramatic. But that’s what happened.

“It’s not cancer,” I said, waving the idea away with my hand.

“Actually, the vet said it could be cancer,” she told me. “He’s going to take it off.”

Ceece seemed cold and angry, shutting me out. It wasn’t lost on me that I was the same way at her age after l’d lost my mother, and that her mother was the one who had saved me. It was also a lot of pressure. I worried she was not OK, but I didn’t know how to help.

Ceece sent out resumes, watered her cactus and took her dog in for surgery. Sometimes she didn’t come out of her room all day.

Then came the time we went for a walk around Lake Hollywood. It was a perfect Los Angeles day, after the rain, crisp air, a turquoise blue sky. Suddenly the Hollywood sign came into view.

“The first time your mom came to L.A., I took her to see the sign,” I told her. “You know how she was. Loved celebrities. Called them ‘stars.’”

“She was a great person,” I said. “She changed my life.”

At first Ceece rolled her eyes. Then she asked me to tell her about her mom. So I did. After that day we explored the city together. We went to the farmers’ market, the county museum, Home Goods to shop for throw pillows. I learned she really loved plants, purses and quesadillas. Sometimes, we laughed really hard. Sometimes, we cried. As it turned out, I didn’t need to save her after all. She just needed a friend. So did I, since I’d lost the best one I’d ever had.

The production company ended up not liking the candidate they hired and asked Ceece if she was still open to the job. When she moved across town to her own apartment six months later, I was heartbroken. But I knew how to handle it. After all, her mother had taught me how to have a long-distance friendship. And both the dog and the cactus lived.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What to read when you’re grieving a loved one

By Yvonne Abraham

I am a great grief compartmentalizer. I can put sadness into a box or write about it, pretending to be a detached expert. My therapist tells me I don’t feel it, though. She claims I have one button for all emotions, and that by turning off the grief, I also prevent myself from experiencing joy, hope, and excitement. You can’t get the good without the bad, she claims. I hate that.

There are a zillion wonderful books about loss, but none of them helped me feel. But a script did it. It unstuck the button. “Fleabag: The Scriptures,” Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s compilation of scripts from the show, includes pages of dialogue showing her character’s compartmentalized grief, which was all too familiar. On page 331, in a flashback, Fleabag considers the loss of her mother, and tells her best friend, ”I don’t know what to do with it —” “With what?” the friend, Boo, asks. “With all the love I have for her. I don’t know … where to — put it now.” Reading that, I was able to see all the love for my late mom that has been following me for years, with nowhere to go. I’m learning to give it to others. “I’ll take it,” Boo offers Fleabag. “No, I’m serious. It sounds lovely.”

MEREDITH GOLDSTEIN

Letters for life

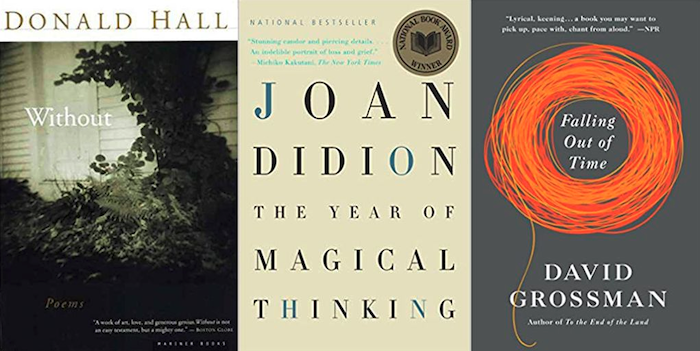

The opening words of Donald Hall’s “Letter After a Year,” addressed to his late wife and fellow poet Jane Kenyon, are: “Here’s a story I never told you.”

Hall proceeds to describe a time, long before he met Kenyon, when he discovered letters in the attic of a rented house that a previous tenant had written to a lover who had died in a plane crash. He recalls his puzzlement back then: “She’s writing to somebody dead?”

But Hall came to understand, and act on, that same impulse after Kenyon died at 47. The proof of that is “Without,” a 1998 collection of poems (many of them with the word “Letter’’ in the title) that falls somewhere between conversation and correspondence. These poems are written about and to Kenyon, who succumbed to leukemia in 1995 on the New Hampshire farm where she and Hall lived.

Now, it would be a mistake to read “Without’’ in the expectation of bromidic uplift. Hall was too honest a poet — and too faithful a husband — for that. There is overwhelming pain in these pages, numerous times when, in Hall’s words, “grief’s repeated particles suffuse the air.” In “Letter in the New Year,” Hall writes to Kenyon that “this new year is offensive because it will not contain you.” For him, grieving is not a linear process but a flailing struggle to stay afloat amid a flood.

Yet within the quasi-epistolary structure of “Without” can be discerned the hope that, on some indefinable level, a relationship is not over so long as one partner lives. Hall updates Kenyon on the doings of children, grandchildren, and friends; he tells her about watching the Red Sox; he describes the springtime arrival of goldfinches and the emergence of daffodils on the hillside. And he evokes the numberless little moments that made up their life together, from shopping to lovemaking to holiday rituals like Kenyon’s habit of opening the daily Advent calendar window and then reading the Gospels. “Ordinary days were best, when we worked over poems in our separate rooms,” Hall tells Kenyon.

To be “without,” obviously, is a fate that befalls many of us. What Hall’s poems suggest is that memory, and perhaps an untold story or two, can help sustain just enough “with” to pull us through.

DON AUCOIN

Walking with grief

Grief of any kind obeys a logic all its own. But a parent’s grief over the loss of a child must defy logic altogether. “Because how can one articulate logical, coherent, human speech when the foundations of logic and proper order, the so-called natural order, the order whereby parents should not mourn their children — have foundered?”

So writes the Israeli author David Grossman, who lost his own son in Israel’s Second Lebanon War in 2006. Some five years after that shattering event, Grossman, in keeping with this observation, corralled the materials of his own mourning not into a coolly coherent memoir but into a kind of haunting parable.

A grieving man gets up from dinner one night and sets out to walk around his village in ever-widening circles. He has left behind normal life to search for his departed son, to seek out an elusive place described only as “there,” to trace on the land his own spiraling itinerary of loss and boundless yearning. The man begins his walk alone but is quickly joined by others who have also lost children, each one inevitably trapped within a kind of private exile yet now, suddenly, walking together.

Narrated in spare, poetic language, “Falling Out of Time” is a story of reckoning and reclamation — of learning to live with, and without, the dead. The novel, which was recently adapted by composer Osvaldo Golijov into a tone poem of the same name, also constitutes its own act of co-walking with the grieving, a way of broadening outward from sharp solitude of private sorrow. Finally, it is a meditation on the working through of a wild, impossible grief until the point that, as Grossman writes, “there is breath inside the pain.”

JEREMY EICHLER

Keep moving forward

“It’s okay. She’s a pretty cool customer.”

That’s what a social worker says to a doctor who’s wondering how to tell Joan Didion that the heart attack suffered barely an hour ago by her husband, the novelist John Gregory Dunne, had proven fatal.

Anyone who knows the chill, clipped control found in Didion’s novels and essays realizes how well “cool customer” describes her as a writer. How it does and doesn’t apply to her as a grieving widow is the burden of “The Year of Magical Thinking.” It won the 2005 National Book Award for Nonfiction, but to think of so searching and personal a work in terms of something as transitory as a literary prize doesn’t so much miss the point as ignore it.

The point is that neither grief nor life stops. It’s not just the consequences of Dunne’s death that Didion writes about but also dire health crises affecting their daughter, Quintana, over the same period of time. To lose one’s spouse and then possibly one’s only child? The Old Testament may offer the closest literary counterpart: the Book of Job. That “Magical Thinking” and its author merit the comparison is no small compliment to Didion as writer and human being both.

MARK FEENEY

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Anxiety Is a Stage of Grief You May Not Recognize

You’ve probably heard of the stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. However, grief is a complex and personal experience, and there are many aspects of it that don’t fit neatly into this model.

One common, but often unrecognized, grief response is feelings of tremendous anxiety. Some individuals may be aware that they’re feeling anxious; for others, it’s hard to identify specific emotions that make up their overwhelming pain.

Grief-related anxiety is often rooted in our concerns about how we will cope. When we experience a significant loss, it can feel like our world is falling apart around us, and we wonder whether we’ll fall apart, too—especially if we’re grieving a loved one whose support we depended on in exactly these kinds of situations.

We might also have counted on a person in practical ways, and wonder whether we can shoulder the increase in responsibilities. For example, the untimely death of a spouse might require a person to adjust to the demands of being a single parent. When we’re focused on our sadness and loss, it might be hard to realize that we’re afraid, too.

It’s disorienting when we lose someone or something that’s integral to our lives, and it can trigger the fear of what else we might lose. The death of a parent, for example, might trigger worry about losing the other parent, or one’s spouse. For many people, the fear is less specific but equally powerful—more a vague sense of threat and unease.

Anxiety can also come from the stress on our minds and bodies, which leads to a state of high alert as our fight-or-flight system is stuck in the “on” position. You might be exhausted but unable to let go of tension—“tired and wired”—which can show up as trouble sleeping and feeling constantly on edge.

Keep in mind that grief can follow many experiences of loss, not just death. We can grieve the loss of a career, and feel anxiety about our unknown financial future. We can grieve the loss of health, and worry about further decline. We can grieve the loss of a relationship, with anxiety about ending up alone.

If you’ve experienced anxiety as part of grief, here are some suggestions that may help you cope:

- Reach out to those around you. No matter what kind of loss you’ve experienced, stay connected to the important people in your life. Few things are more grounding than meaningful relationships. Don’t be afraid to ask for ongoing support—it takes time to grieve, and there’s no expiration date on the comfort of family and close friends. Seek out the support you need as you adjust to your altered world.

- Give yourself time to heal. In a similar way, allow yourself the time needed to process what has happened to you. Beware of the idea that you need to “get back to normal”—your world has changed, and it takes time to adjust to those changes. Don’t be surprised if the grief comes in waves, or is different from day to day. You might have reactions to the anniversary of your loss, as well.

- Reduce optional stress. Part of healing is treating yourself gently while you’re grieving. It is probably not a good time to take on difficult new projects or challenges. This is not to say that you’re weak, but rather to direct your strength wisely. Also look for opportunities to process stress and loss in ways that work for you—for example, meditative practices, exercise, massage, or walks with a friend.

- Make space for whatever you’re feeling. There’s no wrong way to grieve. Sometimes we suppress our feelings because we don’t understand them, or we’re scared of them, or in some way we think we don’t deserve to have them. Whatever you’re experiencing is OK, whether it’s sadness, anxiety, a feeling you can’t describe, or any other aspect of grief.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

11 Salves for Holiday Grief in the Time of COVID.

Grief during the holidays is tough enough.

Now, let’s pile on a pandemic for the past year, and you have an even more difficult holiday season.

Being isolated and disconnected from our usual support systems has been a great hardship for many—most certainly for those who have lost a loved one. As the holidays approach, those who are grieving find themselves further burdened by even more unknowns.

Here are some suggestions and perspectives to consider for this holiday season if you are grieving or if you know someone who is grieving.

A Holiday in a box

If you can’t get together with loved ones because you are not traveling or they are not traveling, put together a “Thanksgiving in a box” or “Christmas in a box” or “Chanukah in a box” or “Kwanza in a box” or “(insert your holiday) in a box.” Let this serve as a sort of care package with more than just gifts. Include things like games, puzzles, poems, books, sweets, and other things that you may have shared if you were together.

Easy meals

If you choose to be alone this holiday (which is perfectly fine), opt for a TV dinner or preprepared meal. Many are tasty and include the traditional holiday foods. This also reduces stress in prep and cleanup. Or have your meal delivered. So many stores and restaurants are increasing their deliveries and offering yummy options for the holidays.

Forgo the “have-tos”

Often, the holidays are propelled by the traditions we have, which in and of themselves are not bad. However, if you don’t feel like putting up a tree or lights, or making certain foods, even though you have done that for years with your deceased family member, there is no obligation to do so. Sometimes other family members may be challenged by this; kids may want the traditions to be the same (even if they aren’t going to be around this year). The only obligation you have is to yourself. Do what you want to do this year.

Listen to your wants

If you want a smaller scale (or larger scale) decorated home this year, that’s fine. One woman I know vowed not to have any decorations this year. She and her deceased husband normally put out lots of decorations, but she didn’t have the energy for that now. However, when she found herself at a local big-box store, she was inspired to buy lights. She heard within herself, “Bring light in this year.” At another store, she was drawn to a small living tree, which she plans to plant in her garden after the holiday. She listened to herself. Even though she had thought she wasn’t going to decorate at all, that inner voice offered something different and something meaningful for her this year.

Conserve your energy

What can you make happen with the energy, time, and resources you have? And what is just not possible? The holidays often compel us to extend ourselves beyond our means, both financially and energetically. This could fit into the “have-tos” section as well. Gifts, especially, are not the purpose of the holidays—connection is. If you don’t have the energy and time, ask yourself what matters to you now and how can you do what matters with what you have? This is a question many who are grieving ask daily: What matters to me now?

Focus on the long-term

This year, connecting and being together means something different. If we are not with the people we want to be with now because we don’t live together, it is advised to remain separated. Especially for those who are older or already compromised in some way, don’t risk the unknown and long-term effects of this illness for short-term experience. The most serious long-term effects are hospitalization and death. Conserve your energy and time by connecting virtually. If you live in a warmer climate, you may be able to gather outside. Again, take the proper precautions. Remember that in the long-term, we will be able to be together again. Someone said, “A large gathering this holiday is not worth a small funeral later.”

Allow yourself to change your mind

Even if you want to do something with others, it’s okay to change your mind, even at the last minute. It is helpful to prepare others for this too. Tell them, “I need to warn you that I may need to change my mind, depending on how I feel.” People who know you and know your situation will understand. This also applies to events you may sign up for online. When you register for an event, check the refund policies.

Sit this one out

Some who are grieving don’t want to be a part of anything related to the holidays this year. This is just fine. While some people (even some close to you) may feel this is not a good thing, you have to decide what is right for you. Sitting out this holiday doesn’t mean you will never celebrate again. It just means for right now, you need to be with you, figure out what you want, watch or listen to what you want, eat the food you want, cry when you need, sleep when you need, and talk to who you want to (or not). Remember, you are the boss of you.

Celebrate when you can

For some, celebrating on the actual holiday is not possible or even desired. Some folks gather (even virtually) before the holiday or after it. One person said they celebrate the holidays in the summer when everyone can make it. It’s too late for that this year, but maybe you’ll choose that next year, after we, hopefully, can gather again. Getting together in the summer will allow for an even sweeter celebration.

Pulling inward

As we go into the darkest time of the year, our natural inclination is to hibernate. For those who are grieving, this can be a greater pull. With the holidays being so different than they ever have been, it seems like we have an even better reason to pull inward. We can shift our focus from outside ourselves to within ourselves, from doing to being—being with ourselves, being with others (mostly virtually), and being with what is, right now.

Be in the present

This year, we have experienced how things can change day-to-day. Being present for the experiences right now will support you in your grief. Being present to how you feel can help you to make choices about what you want and how you want your life to be. Worrying about what is out of your control expends energy that could otherwise be used for what you can control. Being present allows you to ask, “What is in my control now?” When we discover what is in our control, we find we have more choices. When we focus on what is out of our control, we find fewer choices and feel more helpless.

If you need additional assistance as you are grieving in this time, there are many folks who can help and support you. Local hospice organizations often have resources, especially during the holidays. There are many websites that offer written, video, and even live/Zoom events with information and support. If you find yourself struggling and need immediate assistance, call 911 or your local emergency mental health services for support.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Sacred Songs for the Dead

Women had few powers in Ancient Greece – except in death.

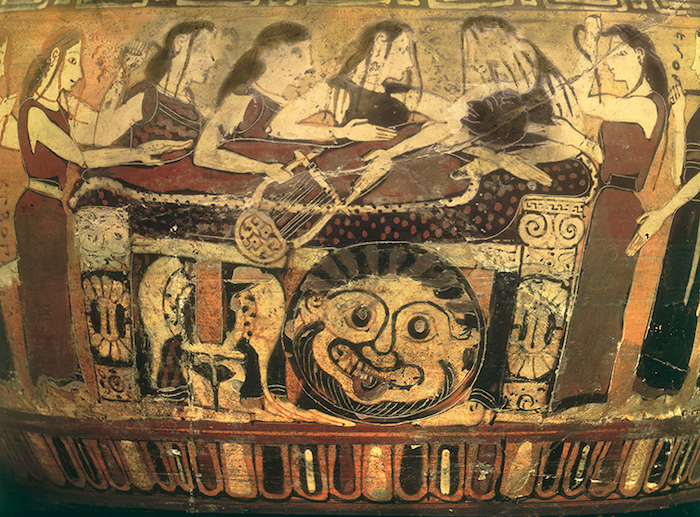

Demonstrating grief through wailing and song has long been a historic, sacred part of honouring and remembering the dead. From the Chinese to the Assyrians, Irish and Ancient Greeks, oral rituals of outward mourning were a responsibility that fell (and continue to fall) to women.

In Ancient Greece, while women may have lacked political and social freedom, the realm of mourning belonged to them. Their role in remembering the dead granted them their only position of power in a society where they possessed no autonomy. Yet this power was also believed to supersede mortal constraints, giving women the ability to do something that men could not.

The Greek funeral was composed of three parts: the prothesis, or preparation and laying out of the body; the ekphora, or transportation to the place of burial; and the burial of the body or the entombment of cremated remains. It was during the prothesis that the women began their ritual of lament. First, they cleansed the corpse, anointed it and decorated it with aromatic garlands as it lay atop its kline (bier). Once the body was prepared, scores of female relatives gathered around it to beat their breasts and tear the hair from their scalps as they sang funeral songs. They wished to communicate the awful weight of their grief in order to satisfy the dead, whom they believed could hear and judge their cries. In contrast, the men kept their distance to salute the dead, physically signifying their separation from the realm that belonged to women. Some art from the Geometric period suggests they may have joined the female mourners in writhing to the lament, though they were spared from the excruciating gesture of ripping out their hair.

The funeral song served as an extension of the physical pain women inflicted upon themselves during the prothesis. Its purpose was to communicate a cry of uncontrollable pain, a hysteric melody that was believed to be rooted in feminine emotions; thus, only women could be the vessels for this pain. In the depths of their sorrow and self-torture, female mourners in the Geometric period would have sung a melody from one of the four major funeral song categories: threnos, epikedeion, ialemos or goos. These songs were personal and meaningful to the bereaved. In her book Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry (1979), which, through the art they have left behind, analyses how the Ancient Greeks viewed death, Emily Vermeule writes that goos was the most intense kind of funeral song. It might have been reserved for lovers or close family members, as its theme was centred on the relationship between two lives shared, the one now lost.

Leading the funeral lament was the song leader, also called the eksarkhos gooio, or the chief mourner. In early times, she was a professional mourner, but could also be the mother or close female relative of the dead. The song leader served as the liaison between those who mourned and those who had passed, guiding the bereaved through the proper course of remembrance in order to mollify the dead. As she led the female mourners in lament, she was careful to cradle the head of the corpse. Touch was necessary in order to open the ears of the dead. But once the ears were opened, the living women had to tread carefully. Not only could the dead hear funeral laments sung for them during the prothesis, they could also determine whether the presence of the living was good or malevolent. This is the reason, writes Robert Garland in The Greek Way of Death (1985), that Odysseus is advised against participating in Ajax’s funeral. Mourners entrusted their song leader with the responsibility of appeasing the dead to ensure their smooth transition into the spirit world.

As time went on, the role of female song leader would serve as the predecessor to an occult offshoot, the goes, who used song as a vehicle to transcend mortal constraints. Under the goes, funeral songs were no longer songs: they were spells, used to lure the dead back to earth. The goes was akin to a witch, due to her supernatural powers; she had even mastered the art of necromancy and could temporarily bring corpses back to life. Yet, even before the goes and the eksarkhos gooio, women in Ancient Greece had ties to the occult side of death. If the eksarkhos gooio was the mother of this occult tradition and the goes the maiden, the egkhystristriai was the crone. Before the classical period, the egkhystristriai was believed to have officiated at the burial of the body. Like an occult high priestess, her powers stemmed from the ritual of making blood sacrifices to the dead. Later, these sacrifices turned into the more modest ritual of offering libations, exemplified as Antigone pours offerings over her brother Polyneikes after she performs rites over his body.

By the fifth century BC mourning rituals had become less elaborate and deliberately reduced the importance of the female role. The number of female lamenters who surrounded the dead dwindled from scores of close relatives to only a few. Laments became more antiphonal and grew to involve men. Gestures such as tearing the hair were replaced by the symbolic gesture of cutting the hair short. These later changes suggest that the Greeks believed their dead were in less need of appeasement, eradicating the need for a song leader with supernatural inclinations. But they attempted to diminish the role that women had in the death process, thus dismantling a space in which women held dominance. In the classical period, women were relegated to the background of the funerary ritual, writes Maria Serena Mirto in Death in the Greek World (2012), because men feared it would threaten social cohesion and their desire for death to be pro patria, for one’s country. This is evident from Greek state funeral records, such as that in Kerameikos, the Athens cemetery, in which female lamenters are only briefly mentioned, suddenly peripheral to the ritual they had previously orchestrated.

The trend of removing women from the centre of death is not exclusive to Ancient Greece. While some cultures, such as the Assyrians, fought to preserve the role of female lamenters, others have been unable to do so.As Richard Fitzpatrick reported in the Irish Examiner in 2016, in Ireland, the tradition of female keeners, who wail in grief, began to die out in the mid-20th century. In the United States, male funeral directors replaced the long-standing tradition of female layers-out. Women were left behind, as the funeral directors attempted and succeeded at monetising the death industry, a legacy that continues to haunt the recently bereaved, who must deal with costly funeral arrangements.

Today, however, we find ourselves in the midst of a death renaissance, spearheaded by morticians, activists and artisans alike – a majority of whom are women. Ancient mourning rituals and traditions are resurging. Perhaps the role of the female song leader as a spiritual caster of spells will find its way back, too.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The Grief That Is, The Grief that is Coming

I have smelled grief on the air for years. The ache of loss, of losing, of having lost.

As the northern hemisphere moves into the winter, the wind blows in the reminder that so much will be lost. I’ve seen the posts of people I don’t know, but who are close to those I do, sharing stories of family members getting sick or dying of COVID.

It’s getting closer. Faster. The air is thicker with uncertainty.

Of realization that there is no one coming to save us from this virus.

Because there is no quick fix. There is no perfect protection.

(I know this is grim.)

I know these times are more dangerous because of the fear. I have seen it cause even the most steady folks to sway. Some to risky choices. Some to conspiracy.

I know I am in a moment that history will look back on and point out all of the wrongs.

But this is not a measured conversation where I can hide behind lovely words.

There are people dying.

Not Enough Space for the Names

I was on a social media page and someone talking about an altar with candles for the dead on their heart. And that there wasn’t enough space for all of the candles.

After all, more than 250,000 in the United States (and many more by the time this is posted) requires a large space. An impossibly large expanse of holding.

I want to light candles for all of you. I want to brighten this time with your names.

And I want to hold space for the ones who have watched. Watched loved ones die. Said goodbyes over video. Begged to be in the room only to be turned away.

Safety. Not you too.

What is Coming (Soon)

In the beginning, I read a lot about anticipatory grief. The knowing that loss is coming and not being able to stop it.

My heart remembers when my dad was diagnosed with COVID. And the days of blurry, fuzzy thinking. Trying to make decisions as a family about what we would do if…

Touch and go. Faith and fear.

Prayers. Offerings. Outbursts.

I have a stubborn heart, I know. I have clung to believing people are good overall. They will look out for each other. I’ve seen it. I have relationships that have proven it.

But when I look outside my carefully curated community…

I weep.

I am likely not sharing anything that hasn’t been said. I know there are many more that feel this way. Alone. Helpless. Quietly screaming.

Arguing with ‘friends’ on Facebook doesn’t help. Posting the millionth meme about wearing masks doesn’t ease the tension. Staying home only gives more space for the feelings to become louder.

There is grief around the corner. There is grief in the hallway. There is grief in the pillow underneath my head at night.

Because it is everywhere.

Building a Relationship with Grief (Before)

Whether you have lost or not, whether you have been impacted or not, the grief will be a tsunami. I have been holding back my own waves because I don’t know where they will crash. Into you? Into me? Across the yard?

I have taken to sitting with grief now. I see it as an unscreamed scream. An unhugged hug. The empty place into which love pours and pours and pours.

I sit and I ask grief what it needs.

I have an altar to grief. Where I sit. Where I have an amethyst. Where I have bones.

My heart holds an altar too. Memories live there.

I sit at the altar. Sometimes, I weep. Sometimes, I am silent. Sometimes, I sing.

Sometimes. Nothing comes. Time between time.

I write poems to grief. I write letters.

Even when the words feel empty or insignificant.

The Arrival of Grief

And I realize I am preparing for grief’s arrival. All of the ways I have pushed it back, saying that since I can’t grieve in community, I will be patient.

I will wait. I must wait.

It is the thing these moments require.

The space before.

But there are a lot of echoes waiting to be screamed screams.

I imagine you have come here for answers. For solutions. For spells. For prayers.

Me too.

I just show up for it. I make time for grief. Just as I would for any other relationship.

Just as I would for any other precious moment.

Again and again.

What do you need, grief?

What do you ask?

What do you ask of me?

I am not ready.

But sit beside me.

Tell me everything.

***

How are you preparing?

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How to help a grieving parent

By Jane Vock

Most adult children want to help and support their mom or dad when their partner/spouse dies. It’s a tough situation because you are also grieving the loss of one of the most significant relationships of your life. You can help yourself and your mom or dad by understanding grief and grieving, and the tremendous significance of this loss.

When a partner/spouse dies

The death of a spouse/partner is different from the death of a parent. They are fundamentally different relationships and are held differently in our hearts and minds.

The adult child understands and appreciates more fully what their surviving parent is experiencing if they themselves have lost a partner or spouse. It seems we humans often need to have the experience ourselves to really grasp what the experience is like. Grief and grieving are no exception.

Learn from those who have gone before you

If experience is the best teacher, what is the next best thing? To learn from those who have gone before you. Know that life is harder than you can probably imagine when someone you love dies. Act accordingly.

Adult children have been known to say, “I wish I had been there more for mom/dad.” Why do they say this? They say it because they experience the death of someone close to them and realize how it really knocks us off our proverbial feet. The meaning of the word ‘bereaved’ is “torn apart”. It can be hard to describe grieving. It embodies all parts of ourselves: the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. The difficulty in describing this experience is why many resort to using grief metaphors to describe it.

By the way, if you are someone with guilt or regrets about how you handled your parent’s death (or anyone’s death), you don’t have to hold on to this pain. There is a brilliant project, dubbed the Grief Secret Project. If you have what they call a ‘grief secret’, something you haven’t shared because you feel embarrassed, guilty or ashamed, you can share it there and let go of those negative feelings!

Grief and grieving: natural and normal

Literally every site on grief and grieving refers to it as natural and normal. This is often followed by information on how to tell when a person may need professional help or have “complicated grieving” or even “complicated bereavement disorder.” I am not denying this is the case for some, but for the vast majority of us, grief and grieving does not require the help of a professional.

For sure, there are things we can do to “metabolize grief”, such as telling stories, whether to family or friends or in a grief support group. The point is to be mindful about the unhelpful tendency to medicalize or pathologize grief and grieving. I remember my mom saying that dad was the lucky one because he died first. Some might interpret this as a symptom of depression and that my mom needed professional. When I dug deeper, it seemed to me this comment was based on a realistic assessment of that moment. At the age of 81, mom was living alone for the first time in this big old 4 bedroom home, with 2 lots to maintain, considerably less money each month, and also had to figure out how to do or get things done that dad had taken care of before he died.

If grief and grieving are natural and normal…

What does this mean exactly? It means not getting caught up in stages of grieving, and deciding whether someone is in denial, or in some stage for too long or not long enough. It means not being rigid or imposing how one should grieve, how long one should grieve and deciding when it is supposedly time to “move on”. Your mom, for example, may want to remove your dad’s clothes out of the home immediately, or in a month, or a year, two years later, or maybe never. Does it really matter? Be careful not to pathologize this, despite the feelings it generates in you. You probably don’t know what it means. Your timing isn’t necessarily your parent’s timing. Period.

Changed forever

When someone we love dies, we don’t move through it, “recover” or return to a pre-loss normal. Pointedly, the idea that “closure” even exists has been proposed as outrageous. While we resume life, and it can look like it is back to “normal” from the outside, we are changed internally. That is how significant it is. At best, then, one integrates this loss.

What to do given the significance of this loss?

Experiencing losses, especially the death of someone you love, is both a universal and an intimate and deeply personal experience. Your parent can guide you.

At the level of the everyday and the concrete, you can ask what they want help with or worry most about doing now that their partner/spouse has died. You can help turn that worry into action. For my mom, immediate tasks were lawn mowing and snow removal, and being shown how to put gas in the car!

Be specific when you ask how they are doing. The general ‘how are you doing’ question has become a rather empty throwaway question. Get specific. How are you at night? At bedtime? How are mornings or meal times? The real value of asking is listening to the answer without trying to solve or fix it. It’s the expression of empathy and love and caring that gives the question its value.

Honour the relationship by telling stories and sharing memories. You will obviously have your own stories of your mom or dad, as well as family stories. Share them. Stories and storytelling are powerful and can help us metabolize grief.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!