By Yvonne Abraham

I am a great grief compartmentalizer. I can put sadness into a box or write about it, pretending to be a detached expert. My therapist tells me I don’t feel it, though. She claims I have one button for all emotions, and that by turning off the grief, I also prevent myself from experiencing joy, hope, and excitement. You can’t get the good without the bad, she claims. I hate that.

There are a zillion wonderful books about loss, but none of them helped me feel. But a script did it. It unstuck the button. “Fleabag: The Scriptures,” Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s compilation of scripts from the show, includes pages of dialogue showing her character’s compartmentalized grief, which was all too familiar. On page 331, in a flashback, Fleabag considers the loss of her mother, and tells her best friend, ”I don’t know what to do with it —” “With what?” the friend, Boo, asks. “With all the love I have for her. I don’t know … where to — put it now.” Reading that, I was able to see all the love for my late mom that has been following me for years, with nowhere to go. I’m learning to give it to others. “I’ll take it,” Boo offers Fleabag. “No, I’m serious. It sounds lovely.”

MEREDITH GOLDSTEIN

Letters for life

The opening words of Donald Hall’s “Letter After a Year,” addressed to his late wife and fellow poet Jane Kenyon, are: “Here’s a story I never told you.”

Hall proceeds to describe a time, long before he met Kenyon, when he discovered letters in the attic of a rented house that a previous tenant had written to a lover who had died in a plane crash. He recalls his puzzlement back then: “She’s writing to somebody dead?”

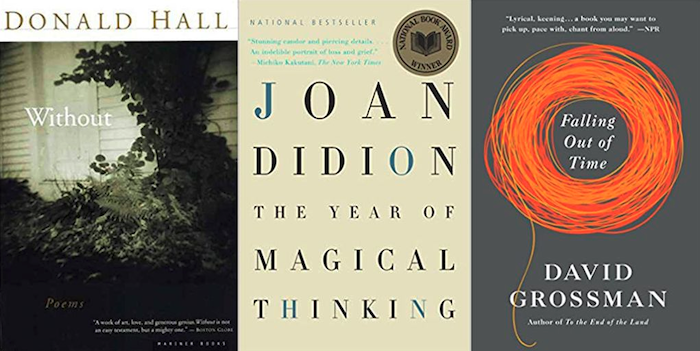

But Hall came to understand, and act on, that same impulse after Kenyon died at 47. The proof of that is “Without,” a 1998 collection of poems (many of them with the word “Letter’’ in the title) that falls somewhere between conversation and correspondence. These poems are written about and to Kenyon, who succumbed to leukemia in 1995 on the New Hampshire farm where she and Hall lived.

Now, it would be a mistake to read “Without’’ in the expectation of bromidic uplift. Hall was too honest a poet — and too faithful a husband — for that. There is overwhelming pain in these pages, numerous times when, in Hall’s words, “grief’s repeated particles suffuse the air.” In “Letter in the New Year,” Hall writes to Kenyon that “this new year is offensive because it will not contain you.” For him, grieving is not a linear process but a flailing struggle to stay afloat amid a flood.

Yet within the quasi-epistolary structure of “Without” can be discerned the hope that, on some indefinable level, a relationship is not over so long as one partner lives. Hall updates Kenyon on the doings of children, grandchildren, and friends; he tells her about watching the Red Sox; he describes the springtime arrival of goldfinches and the emergence of daffodils on the hillside. And he evokes the numberless little moments that made up their life together, from shopping to lovemaking to holiday rituals like Kenyon’s habit of opening the daily Advent calendar window and then reading the Gospels. “Ordinary days were best, when we worked over poems in our separate rooms,” Hall tells Kenyon.

To be “without,” obviously, is a fate that befalls many of us. What Hall’s poems suggest is that memory, and perhaps an untold story or two, can help sustain just enough “with” to pull us through.

DON AUCOIN

Walking with grief

Grief of any kind obeys a logic all its own. But a parent’s grief over the loss of a child must defy logic altogether. “Because how can one articulate logical, coherent, human speech when the foundations of logic and proper order, the so-called natural order, the order whereby parents should not mourn their children — have foundered?”

So writes the Israeli author David Grossman, who lost his own son in Israel’s Second Lebanon War in 2006. Some five years after that shattering event, Grossman, in keeping with this observation, corralled the materials of his own mourning not into a coolly coherent memoir but into a kind of haunting parable.

A grieving man gets up from dinner one night and sets out to walk around his village in ever-widening circles. He has left behind normal life to search for his departed son, to seek out an elusive place described only as “there,” to trace on the land his own spiraling itinerary of loss and boundless yearning. The man begins his walk alone but is quickly joined by others who have also lost children, each one inevitably trapped within a kind of private exile yet now, suddenly, walking together.

Narrated in spare, poetic language, “Falling Out of Time” is a story of reckoning and reclamation — of learning to live with, and without, the dead. The novel, which was recently adapted by composer Osvaldo Golijov into a tone poem of the same name, also constitutes its own act of co-walking with the grieving, a way of broadening outward from sharp solitude of private sorrow. Finally, it is a meditation on the working through of a wild, impossible grief until the point that, as Grossman writes, “there is breath inside the pain.”

JEREMY EICHLER

Keep moving forward

“It’s okay. She’s a pretty cool customer.”

That’s what a social worker says to a doctor who’s wondering how to tell Joan Didion that the heart attack suffered barely an hour ago by her husband, the novelist John Gregory Dunne, had proven fatal.

Anyone who knows the chill, clipped control found in Didion’s novels and essays realizes how well “cool customer” describes her as a writer. How it does and doesn’t apply to her as a grieving widow is the burden of “The Year of Magical Thinking.” It won the 2005 National Book Award for Nonfiction, but to think of so searching and personal a work in terms of something as transitory as a literary prize doesn’t so much miss the point as ignore it.

The point is that neither grief nor life stops. It’s not just the consequences of Dunne’s death that Didion writes about but also dire health crises affecting their daughter, Quintana, over the same period of time. To lose one’s spouse and then possibly one’s only child? The Old Testament may offer the closest literary counterpart: the Book of Job. That “Magical Thinking” and its author merit the comparison is no small compliment to Didion as writer and human being both.

MARK FEENEY

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!