By LISA ZAMOSKY

Earlier this year, Gary Spivack and his sister Betsy Goodkin lost their mother to cancer. Between her first diagnosis and her death in April, her children say, their mother was determined to overcome her illness.

“She was a very stubborn and proud person who fought this and had a lot of support from immediate family and a lot of friends,” says Spivack, 49, a music industry executive who lives in Pacific Palisades.

“She was going to live out her final minutes as healthy and fighting it as much as she could,” adds Goodkin, 51, who describes herself as a “full-time mom” in the Cheviot Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles.

But even as their mother fought to stay alive and healthy, her children say, she made her end-of-life wishes known: If death was imminent, she wanted no heroic measures taken to save her life. And she insisted on dying at home.

They said their mother passed away April 13 in just the manner she had hoped: She was in her own bedroom with the lights low and the mood peaceful. She held hands with loved ones as she passed.

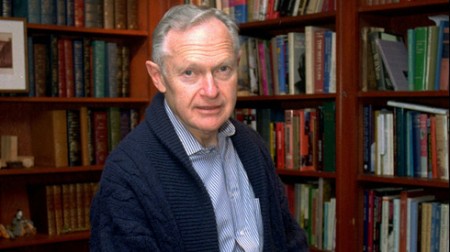

Dr. Neil Wenger, director of the UCLA Health Ethics Center, said most patients would prefer to die that way, but few actually do. That’s because they fail to put their final request in writing, he says.

Without advanced planning, he says, most people die in hospital intensive care units, “in not the most dignified circumstances, in a way most say they don’t want to die.”

Why the gap between what people say they want at the end of their lives and what actually happens? There are many reasons.

A recent study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that lack of awareness is the most common reason people cite for not having written instructions prepared in advance.

“People go into a mode of thinking — and are encouraged to — that ‘if I just apply enough technology I will survive it,'” says Barbara Coombs Lee, president of Denver group Compassion & Choices. They even continue “in that mode of thinking when it’s perfectly obvious they are actively dying.”

Doctors also avoid such talks. Some physicians incorrectly believe patients don’t want to discuss death. Others pass the buck, believing it’s some other doctor’s responsibility to have the discussion.

These talks take time and can be emotional. “Doctors are human and they bring to the table a lot of their own emotions about death and dying, and these can be very difficult conversations to have,” said Dr. Glenn Braunstein, vice president of clinical innovation at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

A report out last week by the Institute of Medicine stated that medical and nursing education fails to orient healthcare providers toward less aggressive forms of end-of-life care, and many providers simply lack the communication skills needed to have these conversations.

Also, the report noted, providers are still largely paid to deliver more services, rather than fewer — even when treatment is futile.

Experts offer recommendations for putting end-of-life plans in place and what needs to be considered.

Open up the lines of communication. Frequent conversations about end-of-life goals between doctors and patients are essential if unwanted treatment is to be avoided, experts say.

“When people fail to plan for the worst, often they find themselves in a struggle to avoid an imminent and inevitable death that ends up causing an enormous amount of suffering for them and for their family members,” Coombs Lee says.

“Anyone with a life-threatening disease should know their options and the efficacy rate of any treatment they are offered,” she says.

Insist on shared decision-making. End-of-life conversations should be part of shared decision-making between a patient and his or her doctor, Braunstein says.

“You take into account the patient’s preferences, their spirituality and a variety of things. At the same time the physician should be giving honest information about what the prognosis is, what we can do and what we can’t do,” he says.

Talk about comfort care: Conversations should include discussions about your various treatment options, including palliative care, which emphasizes a patient’s physical and emotional comfort. Braunstein said palliative care should start well before a patient is terminally ill.

Also important is to talk about hospice care — treatment when you are no longer attempting to prolong your life but rather focusing on staying comfortable and managing pain in your final days.

“We think of hospice care delivered in the home as the gold standard,” Coombs Lee says.

Research suggests that people who receive palliative and hospice care may live longer than ill patients who don’t.

Select an agent. It’s a good idea to name someone such as a family member or close friend to serve as your healthcare agent.

This should be the person you most trust to represent your best interests and who will make sure your wishes are respected and carried out. Your agent can’t be your doctor or other healthcare providers treating you.

Establish an advance care directive. These directives for your last days are legal documents. They allow patients to state their treatment wishes and appoint someone to make medical decisions on their behalf.

They should spell out what you want to have happen and what you don’t. They must be signed by two witnesses — not your doctor or the person you name as your healthcare agent. Alternatively, you can have the document notarized.

A copy should be given to your healthcare agent, other family members or friends, and to your doctor. Ask that it be included as part of your medical record.

Get your doctor’s orders in writing. A Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment is a frequently used document to be signed by both the physician and the patient.

It generally is filled out when a person’s anticipated life span is six months or less and is put in a prominent place where caregivers and paramedics can see it. “The document is pink so it stands out, and we tell people to put it on their refrigerator or where they’re sitting downstairs,” Braunstein says.

Goodkin of Cheviot Hills says she learned a lot from her mother’s passing in April, namely about how to die on your own terms.

“Everybody wants to die with dignity, bottom line,” she says. “Whatever that means to somebody, you just have to honor that.”

Complete Article HERE!