BY COLLEEN DISKIN

At 92 and with cancer spreading through her body, Gloria Luers knew she didn’t have much time. She began contemplating her final days, saying she wanted to be surrounded by family and to listen to stories and her favorite music.

But in those last days, she would also have strangers join the round-the-clock vigil at her bedside, people she had never met but who would nevertheless walk into her room knowing that she liked Italian tenors and the lumbering sounds of her great-grandchildren at play.

These strangers, all volunteers, would be there to comfort and console Luers and her family as death neared, making sure her final wishes would be followed and that her dying days paid homage to her living ones.

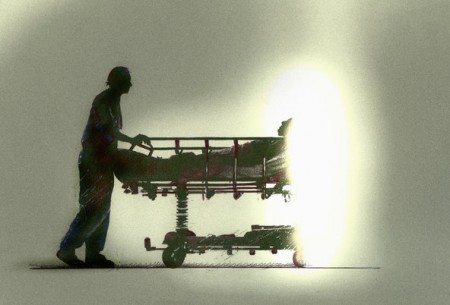

While hospice workers would manage her physical pain and guide her care, the volunteers, known as end-of-life doulas, would be there so family members could sleep and take a break, supporting everyone through what would be a long, exhausting experience. Their mission would be to help Gloria Luers and her family remain focused on her life instead of her illness and, in the process, gain some peace.

When the family decided to accept the offer by the hospice program to provide the doulas, her daughter, Denise Rich, said she was comforted to know that she wouldn’t be alone if her mother’s death came at a time when her husband was away at work and other family members couldn’t get there quickly enough.

“A big fear of mine is that I’ll be by myself and I won’t know what to do or what she needs,” said Rich, a Cliffside Park resident. “Now I know that there is someone out there who I can call when the time comes.”

The word “doula,” evolved from its ancient Greek meaning of “woman who serves,” has most often been used to refer to someone who coaches a mother-to-be through childbirth, providing emotional support through what can be a scary experience. Henry Fersko-Weiss, a longtime social worker, said it’s a concept that can be applied at the end of life.

Five years ago, he helped start an end-of-life doula program, a free service, at the hospice run by The Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, where the doulas are trained to recognize the signs of approaching death and schooled in easing the stress of a dying person and their families. He is now launching a second program, this one based at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck. Paid hospice staff supervise the two programs, but volunteers provide all the bedside support.

Fersko-Weiss, who also founded the International End of Life Doula Association, said he hopes doulas will one day become part of the standard of care at hospices, assisted-living residences and nursing homes around the world.

“We help people be born into the world, why wouldn’t we also want to help as they transition out of this world?” said Janie Rakow of Wyckoff, a doula with Valley.

Rakow and other doulas were there in the final days of Ellen Gutenstein’s life last April. Her husband and daughter often look back on what it meant for them to have seven strangers come in to help when she began to drift away.

By then, the 77-year-old Gutenstein’s physical world had shrunk to the bedroom she and her husband had shared for decades in their Ridgewood home, her hospital bed wedged next to the couple’s wood-framed, king-size bed. The room was crowded with medical equipment, and the tops of dressers and bureaus were filled with medicine bottles and the other detritus of terminal illness. But it was brightened by pictures of the grandkids and beloved collectibles.

As much as possible, for as long as possible, members of Gutenstein’s family wanted her to remain a part of their lives. But even with her husband sleeping in the bed next to hers, her daughter staying over most nights, and her two sons and grandchildren making regular trips in from out of town, it was hard for one of them to be awake and at her bedside every minute of her last days.

In the blur of that emotional time, Robert Gutenstein has forgotten the names of the doulas who spent three or fours hours each keeping watch while sitting in the chair next to his wife’s bed, including the one who was there at the end. But the family hasn’t forgotten the works they performed.

There was the one who lifted their spirits with her beautiful singing voice. There were the others who read aloud to Ellen from the “legacy book” the doulas had encouraged the family to assemble, an album of photos from vacations and major life events as well as letters and written reflections from her children, grandkids and friends.

“What stands out most to me about the doulas is that they were all so loving with someone they had just met,” said the Gutensteins’ daughter, Lisa Silvershein. “Somehow, they all seemed very familiar, like they just understood and were helping us to be prepared for what was coming.”

Kristen Tsarnas, a volunteer doula, said death is a subject in which society has not advanced for the better.

In the frontier days, when hospitals were few and far between, a family brought a loved one home to die and the community came to bear witness to the leave-taking. “This kind of tending to someone at the end of life is really an old thing that kind of disappeared from our modern society,” said Tsarnas, who lives in Allendale.

In describing her role as a doula, she often uses the word “witness.” “It’s sort of a way for the family to feel the significance of the moment — that this is an important enough event that some stranger came to my house to be there for the end of my mother’s life,” she said.

Her view is shaped by the sudden death of her stepfather when she was 18. He was hospitalized, but not expected to die. So she didn’t return home from college and her mother didn’t stay the night at the hospital. More than two decades later, both are burdened by his being alone when he died.

“No one should be alone in a hospital in a cold room when they die,” Tsarnas said.

Fersko-Weiss sees the companionship and comfort the doulas offer as “the missing piece of the hospice mission.”

Hospice programs provide dying patients and their families with a host of services — nurses, social workers, grief counselors, medicine and medical equipment — intended to ease pain and suffering. But hospices can’t offer round-the-clock staff and while their social workers and grief counselors attempt to prepare families for the final days, he said, many still find themselves overwhelmed by the changes that can unfold quickly at the end of life.

“In my years in hospice, I saw a lot of cases where people are kind of unprepared for the final day,” he said. “I think people don’t take it all in until it’s happening, and by then they are emotionally and physically exhausted.”

The doulas are trained in calming and soothing techniques, such as meditation, aromatherapy and therapeutic touch. Most don’t come from medical or counseling backgrounds, and they are not expected to take on the direct caregiving tasks that hospice staff and home aides perform. Their job descriptions are more amorphous — some see it as akin to social work, nursing or ministering. Others say the mission is simply to be present and ready to serve.

“A lot of our doulas are very spiritual, holistic kind of people who just have a calling to do this,” said Bonnie Schneider, who manages Valley’s doula service, which is offered as a no-cost service to patients in the hospice program.

At a recent training session for the 19 volunteers learning to be doulas for the Holy Name program, Fersko-Weiss stressed the importance of a lead doula paying early visits to a dying person to help create a “vigil plan” that spells out what that individual wants — candles burning, their hands held, poems read and the like. Such plans are shared with all doulas assigned to the case. The doulas need to be sensitive, Fersko-Weiss told the trainees, to the fact some families may have conflicts still playing out, so they should try to encourage family members to express their feelings of loss and to both seek and offer forgiveness.

Since Valley began its program in the fall of 2009, the doulas have participated in more than four dozen vigils, many in private homes, but some in nursing homes or in-patient hospice centers. The typical vigil lasts 24 to 48 hours, Schneider said, and the longest went eight days. Valley’s 40 doulas have worked with many other terminally ill patients and families, helping them to think about how they want the final days to play out.

The doulas are called in at the onset of what’s called the active dying stage, when they exhibit symptoms such as slowed breathing, a drop in blood pressure and a third day of refusing to eat.

For Bob Eid, a doula from Mahwah, being at a death is a profoundly moving experience.

“I think death is a very sacred moment,” he said. “I’m not uncomfortable around it.”

Before Coleen Shea made it her official calling to sit with the dying, family circumstances put her at the bedsides of three of her own.

The first was six years ago, when her 92-year-old grandmother died and the scene at the bedside was like something out of a Hallmark special, children and grandchildren lined up three deep around her bed.

“Everybody was able to lay a hand on her and to tell her what she had meant to them,” Shea said. “Her whole bedside was surrounded. It was exactly how anyone would want it to be. I left there thinking it was an immeasurable privilege to have been there.”

Shea also spent time with two uncles in their final days. Those deaths were less peaceful, but no less moving. She recalls when one uncle suffered a painful seizure a few days before his death. She comforted him by telling him that he had fought bravely and that it was all right to let go.

“I sort of felt like I had made a difference,” she said.

The Glen Rock mother of two compares her doula position to that of a nurse who must move from room to room, tending to different tasks and needs in each.

She doesn’t expect a family to get to know her. Instead when she walks into a new home, she scans her surroundings for the things that most need doing — someone in need of a break or a comforting word, or a patient with arthritic hands who might enjoy a massage.

“I’m just as afraid of dying as anybody else,” she added. “But for whatever reason, I don’t shy away from being there.”

Rakow, who volunteers for both the doula and hospice programs at Valley, said she is routinely asked whether being present at so many deaths makes her sad.

“It’s actually the opposite. We feel humbled to be there and uplifted by the expressions of love we witness,” she said. “There are times when family members have had tough times with each other throughout their lives, and you’ll see how that just strips away at the end, and how they come together. It’s incredibly moving.”

Nearly a year after his wife’s death, Robert Gutenstein still regularly pages through her legacy book. The last picture, taken just a few days before her death, is of Ellen celebrating Easter dinner with her family and friends.

“The doulas were just wonderful to her,” he said. “They engaged her in life so that she wasn’t a body sitting in a corner isolated from things.”

The family came to rely on the ever-present doulas in Ellen’s final days. “At that point, you don’t want to leave her alone,” said Silvershein, Ellen’s daughter. “Because the doulas were there, we were able to sleep. It was just kind of nice to put somebody else in charge.”

Silvershein was headed to bed a little after 11:40 on Friday, April 25, when she stopped into her parents’ room to say good night. She and the doula noticed a change in her mother’s breathing pattern and woke her father, who had been asleep for a few hours in the bed next to his wife’s.

“I’m half-asleep,” Robert Gutenstein recalled. “I put my hand on her hand, she gives me a squeeze, and that was it. She stopped breathing.”

Rakow, who had served as the lead doula on Ellen’s case, arrived at the home with bagels for breakfast the next morning. Several doulas attended the funeral. A month later, Rakow and Silvershein together talked about the shared experience.

Silvershein credits the doulas with helping her find her way in those emotional days. Because a person’s hearing can be the last sense to go, the doulas encouraged her to keep reassuring her mother, even after she drifted out of consciousness.

“They told me, ‘Tell her you love her, tell her that Dad is going to be OK, and that we’re all going to be OK,’Ÿ” Silvershein said. “I don’t know that I would have thought to say all of those things without the doulas being there. I feel like they just guided us through the whole experience.”

A month ago, on a visit with Gloria Luers to plan what she and her family might need from the doulas, Fersko-Weiss asked about the sights and sounds that bring her comfort. In addition to music, she talked of the frequent visits of her young great-grandchildren, who call her “GGMa.”

Her memory still firm and clear, she regaled him with anecdotes from a girlhood living without a mother, her husband’s war years and the years she spent tending to children and grandchildren. “I am good at telling stories, and I have some good ones to tell,” Luers said. Fersko-Weiss pledged to write them down and help her family assemble a legacy book for her loved ones.

Luers began to decline a week ago, no longer able to speak and unable to get out of bed, and was moved to the Villa Marie Claire hospice in Saddle River. Her daughter stayed over most nights and her son and grandchildren visited often.

On Wednesday, five doulas began taking shifts, playing songs sung in Italian by Andrea Bocelli and sitting with family members as they shared stories and talked about the Fort Lee home where Luers raised her family.

“It was a lot of reminiscing and talking about the things that stood out about her in life,” Fersko-Weiss said.

About 9 a.m. Friday, as Gloria’s breathing became shallow, Fersko-Weiss woke her daughter, who was sleeping in another room after being up much of the night with her mother.

Gloria Luers died about 15 minutes later, with both of her children, a grandson and Fersko-Weiss — not a stranger anymore — at her bedside.

Complete Article HERE!

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2400318/sidebar-image__1_.0.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919162/gawande_chart_1.0.png) (Metropolitan Books)

(Metropolitan Books)/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919212/gawande_chart_2.0.png) (Metropolitan Books)

(Metropolitan Books)/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919148/vox-share__43_.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919326/Screen_Shot_2015-01-09_at_10.43.30_AM.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2920092/vox-share__51_.0.png)