Societal beauty standards follow us to the grave.

It’s impossible to aestheticize death, but we still try. Shortly before the pandemic reached lockdown level last year, my 101-year-old grandmother died. When my mom proposed that I help her dress the body for the viewing, I obliged despite the fact that I creep out with ease. My grandmother was such a central figure in my life and I wanted a more private opportunity to say goodbye.

The experience fulfilled that expectation, but it also taught me that the process of prepping a body for burial is a vivid reflection of our relationship with societal beauty standards—an interminable dance that continues even after we die.

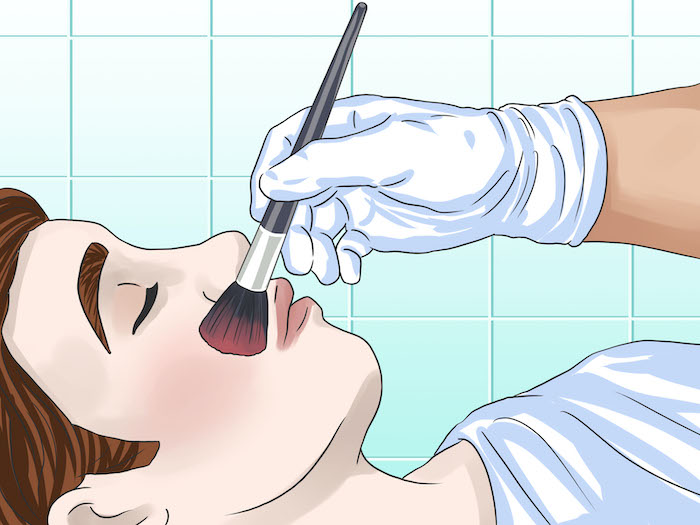

When we arrived at the funeral home the day before the viewing, the staircase leading us to the room where her body was kept felt like it spanned miles. What if she suddenly reanimates? If I tugged on a limb too hard, would it detach from the rest of her body? Once we got started, my anxieties were assuaged but my curiosity piqued. I knew that mortuary makeup was a common practice, but I didn’t anticipate how thorough the grooming would be; her skin had to look supple, her cheekbones had to look lifted and her complexion had to appear even and, at minimum, rosy-adjacent, given the circumstances.

The most shocking sight, though, was seeing the funeral director stuff my grandmother’s bra. After eight children and 101 years, the jig on perky breasts had long been up. So, what was the reason?

“I don’t know how I feel about stuffing bras, but it’s definitely something that embalmers do,” says L.A.-based funeral director Amber Carvaly. “It’s very commonplace and the idea is that people will look different laying down. But they’ll obviously look different because they’re dead and they’re lying in a casket.”

In a 2018 episode of Keeping Up with the Kardashians, Carvaly gave Kim Kardashian—who is, by many standards, an archetype of the eternal fascination with youth and beauty—a step-by-step on mortuary makeup. To elucidate the idea behind the practice to me, Carvaly compared it to the philosophy behind Kardashian’s controversial Balenciaga Met Gala look. Basically, we each have distinct signatures that we like to be known by while we’re alive and ideally, these become the attributes that we’re remembered by after we’re gone. Which means that it’s never ideal for a dead person to actually look dead.

“Kim’s image and who she is and what she looks like is so iconic that you don’t even have to see her face or an article of clothing. She can just be draped in black and you know exactly who she is. Like that’s her brand and her icon.”

In the funeral industry, this would be likened to a “memory picture”, a term Carvaly introduced me to during our chat. In essence, it refers to the lasting image of a decedent that’s ingrained in the minds of their loved ones. “It’s a memory of who they used to be,” she explains.

It wouldn’t be a stretch to liken our desire to make the dead look life-like to the ongoing obsession with looking younger, or to attribute the latter to a society-wide fear of dying. This is something that can’t be color-corrected, concealed, or glossed over.

“We are obsessed with image as society and as individuals,” Carvaly says. “But this idea is implanted while we’re alive. As women, we’re so obsessed with anti-aging and it sort of emerges from a fear of death.” Carvaly says that this even shows itself in how beauty trends evolve. “They change to keep us looking younger and if you wear a trend that’s from the past, it dates you,” she says.

We want the memory picture to capture our loved ones at their best, so the measures that we go to to bring corpses to a perceived standard are just symptoms of the widespread idea that younger is always better.

“We’re a death-denying society,” Carvaly adds. “We don’t like to talk about it, we don’t like to accept it, we don’t like to look at dead bodies because all of it just reminds us of our own mortality. We do so much of that while we’re alive, so of course it carries into death. We don’t even want to look at old ladies on screen—we only want to see people when they’re young and beautiful.”

But while this is a reflection of Western culture’s image-conscious underbelly, the process itself was therapeutic for me. My grandmother died overnight and I slept through my mom’s calls and texts to come to the hospital. Helping to dress her felt like an atonement for not being there, beckoning back to times when I would paint her nails, help to pick her church hats, or watch her apply baby powder with a glamorous, fluffy powder puff. It’s how I cared for her and how she cared for herself. “I think that from a standpoint of beauty as a ritual and beauty as a way to care for people, it’s something different. It’s grooming as a form of love instead of beautification to suit industry standards,” Carvaly tells me.

When Carvaly’s friend Maria passed away, applying makeup to her corpse was a way of honoring how she liked to be seen; while she was alive she was seldom seen without a red lip. “If someone had been like, ‘Don’t put lipstick on her!’ or, ‘She’s dead. Don’t glam her up,’ she would have haunted us,” Carvaly recalls.

Both my experience and the concept itself are multifaceted: I was comforted by the ritual, but alarmed at the extent to which it was practiced. We beautify the dead mostly with the living in mind: to filter the intensity of seeing a corpse, to create a comforting pre-funeral ritual, and to pacify the most pressing reminders of our own mortality. But our discomfort with aging and death is tampering with how we live, and that’s something that no amount of makeup can mask.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!