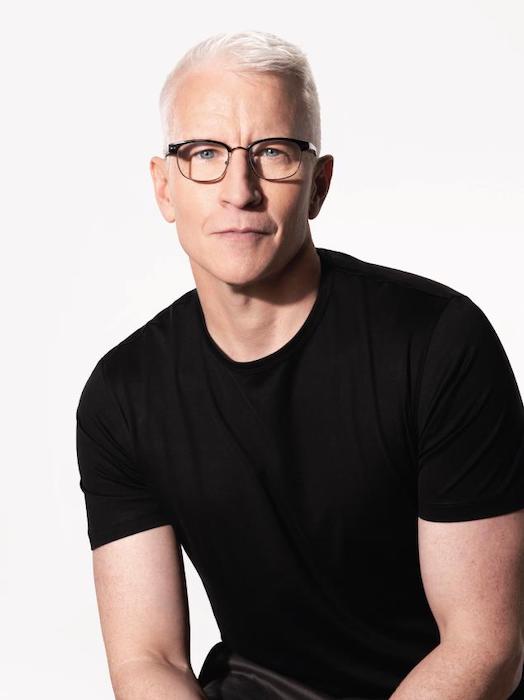

— After the death of his mother, the CNN anchor launched a podcast, All There Is, that gave him a deeper understanding of grief.

By Robert Firpo-Cappiello

Anderson Cooper didn’t intend to launch a podcast devoted to grief. But after his mother, fashion designer Gloria Vanderbilt, died in 2019 at age 95, the CNN anchor started going through boxes of her possessions. A lot of boxes. “She kept everything,” Cooper says. In addition to clothing, letters, photos, jewelry, and art, he found items that had belonged to his father, Wyatt, who died of heart disease when Cooper was 10, and his brother, Carter, who died by suicide when Cooper was 21.

Sorting through decades of personal items reminded Cooper that he was now the only surviving member of his immediate family. After years of covering cataclysmic world events, including wars, natural disasters, and humanitarian crises, “I found myself overwhelmed by this wilderness of grief,” he says. “One of the ways I got through it was by creating a narrative. I started recording voice memos of my thoughts and feelings on my phone.”

Cooper’s instinct to record his response to sadness was an important step toward healing, says Lisa M. Shulman, MD, FAAN, endowed professor of neurology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and author of Before and After Loss: A Neurologist’s Perspective on Loss, Grief, and Our Brain. For Dr. Shulman, writing her book following the death of her spouse, Bill, whom she describes as “more than a husband—colleague, mentor, confidant,” allowed her to express raw emotions and make sense of what she was experiencing. “Grief is emotional trauma. It scrambles our life narrative,” she says. “The trauma activates the amygdala—often described as the fear center of the brain because its function is to monitor threats in our environment—and the amygdala often becomes hypersensitive and hypervigilant, resulting in post-traumatic stress disorder. It becomes more difficult to summon the centers of reasoning and judgment in the advanced brain. Reconnecting with logic and reasoning through journaling, both written and recorded, is helpful.”

One by one, Cooper’s voice memos did have a soothing effect. They also began to add up to a substantial body of work, which he thought might help others who were grieving. “I’ve always been empathetic to the loss and pain in others,” he says. “I think that’s what first drew me to travel to Somalia to cover the famine in 1992 for Channel One.” While that empathy still motivates much of his work as a journalist and as an advocate for suicide prevention, his personal struggle with grief had been pushed down deep. “But you can only do that for so long,” he says. “After my mom’s death, I had no choice but to face it. I realized I could deal with my own feelings of sadness in a journalistic way—as a correspondent from the world of grief.”

From that concept, a podcast was born. All There Is, in which Cooper shares his personal reflections on grief and invites guests to tell their compelling stories of loss and resilience, debuted in September 2022. Although he had doubts as to whether this deeply personal project would find an audience, within two days of its launch it topped Apple’s podcast chart in the United States.

Much like his voice memos, the podcast episodes took shape through an improvisational method rather than advance planning. “As I’d find things among my mother’s belongings, I’d go down new rabbit holes. I’d find Christmas cards from long ago or a box of my father’s belts. I’d struggle to throw anything away. It all became inspiration for podcast conversations.”

Cooper initially recruited guests from his circle of acquaintances who’d experienced significant loss and were able to offer different perspectives, such as how losing a parent influenced their lives or how being present during a death left a lasting, often spiritual, imprint.

Perhaps the most powerful episode featured Late Show host Stephen Colbert, who lost his father and two of his brothers in a plane crash when he was 10. “Stephen believes his loss has made him more human and allowed him to love more fully,” Cooper says.

The composer and performance artist Laurie Anderson discussed the deaths of her husband, rock singer-songwriter Lou Reed, and her beloved dog Lolabelle. “Laurie was with Lou when he died, and she believes death is the release of love,” Cooper says. She made a keen observation about his own grief: “After my mom’s death, I was caught off guard by a feeling of loneliness—the little boy I’d been was no longer known. Laurie said, ‘Yes, that little boy died.’”

Another guest, writer and poet Elizabeth Alexander, talked about the sudden death of her husband and her realization that to persevere in the face of great loss one must “hold it all gently.” Comedian Molly Shannon said the death of her mother, baby sister, and cousin in a car crash when she was 4 contributed, counterintuitively, to her development as a comic writer and actor. And BJ Miller, a hospice and palliative care physician whose sister died by suicide when he was in medical school, said he learned to accept that he might never understand why, and could live without knowing.

Filmmaker Kirsten Johnson talked about her Netflix documentary Dick Johnson Is Dead, in which she examined the idea of anticipatory grief over the inevitability of losing her father to dementia. Although her father is very much alive throughout the film, Johnson stages his death in funny and absurd ways to help them both face the unavoidable.

“Anticipatory grief occurs before a recognized loss,” says Farrah N. Daly, MD, a neurologist at EvenBeam Neuropalliative Care in Leesburg, VA. “Everyone acknowledges that grief occurs when a loved one dies, and usually when this happens people receive support from friends and family. However, with a progressive neurologic illness such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease, many losses occur along the way.”

Family members anticipate what life will be like when their loved ones are no longer with them, says Maisha T. Robinson, MD, FAAN, a neuropalliative care physician and the chair of palliative medicine at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, FL. “Patients anticipate the things that they will lose as the disease progresses, such as their independence, ability to drive, cognition, physical functioning, experiences that they imagined they would have, and the future they envisioned.”

“People may grieve for the future they imagined or the loss of communication or shared activities,” says Dr. Daly. “Because the death has not yet occurred, these feelings might not seem valid, or may conflict with concurrent hopes for improvement. The surrounding community often doesn’t recognize these losses and doesn’t provide much support.”

Cooper experienced anticipatory grief when his childhood nanny developed Alzheimer’s. “I watched her go through a 10-year decline, and I was there at the end of her life,” he says.

Doctors and counselors specializing in palliative care suggest various approaches to easing anticipatory grief, including “role-playing exercises, [which] help individuals embrace anticipatory thoughts and genuinely feel the grief,” says Andrew P. Huang, MD, a hospice and palliative medicine fellow at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

In a typical exercise, says Dr. Huang, “a therapist partners with the loved one in imagining the anticipated, projected outcome they fear—for example, that their father with Parkinson’s will die in the coming months—and asks the person to think about what that would be like: ‘Are you home? What does Dad’s face look like? What feelings come up as you see his face? What images intrude upon your mind as you imagine Dad having just died?’ If the exercise is done in a safe environment, it allows deep feelings to rise to the surface and be experienced rather than suppressed.”

Other ways to counter anticipatory grief are legacy planning and collaborative art therapy. Legacy planning encourages patients and their loved ones to think about the future, says Dr. Robinson. “It involves creating things that would be meaningful to loved ones after the patient dies. This could include writing cards or videotaping messages for their children geared toward events, such as graduations, weddings, or childbirth, that the patient will not live to see.”

Art therapy may involve assembling a photo collage for loved ones that focuses on the life of the patient, finger painting, or simply creating any kind of art together, says Jennifer Baldwin, a grief counselor in Falls Church, VA. “These projects take on even more meaning when the patient has died.”

In her work, Baldwin helps people unravel grief. “I introduce the metaphor of ‘deconstruction’ to explore the event that changed their known world, and then give them an opportunity to reconstruct their world so that they can continue to live in it alongside their grief,” she says. “Through this process people who are mourning have the opportunity to tell their story through a factual lens, an emotional lens, and ultimately a sense-making lens.”

For the season finale of his podcast, Cooper asked listeners to share their personal stories with him, on Instagram or via voicemail, and include something they’d learned that had helped them. Some said they thought being with loved ones when they died was a privilege; others echoed the idea that fully grieving a loss opened them up to more compassion for themselves and others; most conveyed the inextricable link between grief and love.

“I received a thousand calls. I had one week to go through them,” he says. “It was truly extraordinary. I was able to listen to 200 and selected stories for the episode. Before it aired, I called the people to let them know, and I was able to talk with them.” He continues to listen to hundreds of voicemails.

After a successful inaugural season of All There Is, Cooper plans to produce more episodes. “But I’m not sure how many, or what they will look like,” he says. “I don’t want to continue just because I ‘have a podcast.’ I need time to stop and listen to all those voicemails. I’m ruminating on it.”

For Cooper, the podcast has been cathartic. “I learned in talking to people experiencing grief that you can change the story you’ve told yourself,” he says. For instance, he felt exiled and alone after his mother died, but doing the podcast showed he was surrounded by people going through similar experiences. Something Colbert said really stuck with him. “He said, ‘Learn to love the thing you most wish had never happened. Be grateful for what it taught you,’” says Cooper. “There’s comfort in bringing that sadness to the surface.”

In a career covering historic events like September 11, Hurricane Katrina, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Cooper considers All There Is the most valuable thing he’s ever done. “I used to think I had to go far away to witness suffering and tragedy as a journalist. I now realize I can have those conversations close to home.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!