— Reena Lazar and Christa Overnell are working to shift our approaches to end-of-life planning.

By Josh Kozelj

On a balmy April evening, Renna Lazar leaned into the microphone, hushed the murmuring crowd and introduced herself. Then she addressed the topic that attracted roughly 60 people, young and old, to Vancouver’s only operating graveyard. Their death.

“We’re all going to die one day,” Lazar, who is co-founder of Willow End of Life Education & Planning told those assembled at Mountain View Cemetery, “Let’s start thinking about the reality of our mortality.”

In many western cultures, death is a taboo topic that people often avoid discussing — despite the fact that everyone dies. A 2019 survey in the U.K. found that six out of 10 people knew “little or nothing” about what happens at the end of someone’s life.

In Canada, the situation isn’t much better.

A 2016 Ipsos poll reported that just over half of the Canadians they surveyed understood palliative and end-of-life care.

But discussion about death, and how to plan for death, will be more important as Canada’s senior population is expected to skyrocket.

Data from the 2021 census showed that Canadians over 85 were one of the fastest growing age groups in the country. Buoyed by the baby boomer generation, the number of Canadians over the age of 85 will triple in the next 25 years.

That rate has led some to worry about how all of those elders will be cared for in their final stages of life, and whether their families and close ones will be prepared to have difficult conversations about death.

Lazar and co-host Christa Ovenell, founder of Death’s Apprentice, a personal planning and death consultation service, are hoping to shift the conversation around death in the Lower Mainland.

“Some of us might never buy a car, some of us might never get married or have children, but we will all die,” Ovenell said. “People spend more time checking out their cell phone plan than they do thinking about their end-of-life plan.”

The duo has launched a four-part workshop that will focus on a variety of topics — ranging from how to have an environmentally friendly burial to discussing the logistics of medically-assisted deaths — until November.

Following the first workshop, Lazar and Ovenell caught up with The Tyee to discuss why Canadians avoid talking about death. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: What was the motivation to create this four-part workshop?

Reena Lazar: I’ve been touched by death, like so many people. I was in a scary car accident when I was 16 years old where the car flipped.

Fortunately, everyone was fine, but the first thing I did after the accident was take out a pen and paper and write letters to my three best friends at the time. I told them how much I loved them, what I appreciate about them, what I wished for them. I knew I was alive and well, but you come to appreciate life when you’re faced with death. There’s so much written about people in their dying days having these incredible transformations and having an awakening about what’s important to them.

So the whole premise of Willow is to help people “wake up before their time’s up.”

Christa Ovenell: I’m a Willow educator as well, but I’m also a woman in her late 40s who after being impacted by the work of Willow educational programming, decided to quit a high-paying and prestigious job and go into end-of-life care. I became a licensed funeral director and embalmer with the sole intention of messing with the status quo when it comes to death and end-of-life care. Because I believe we don’t really do death right in our society.

Why are we so reluctant to talk about death?

Lazar: I want to say it’s more of a western thing. It’s not a global problem, there are certain cultures that contemplate death all the time.

Ovenell: Industrialization has had a lot to do with why we in the West, in particular, have become so distanced from death as part of life. We just make the problem go away, call the funeral, take the dead person away.

In Victorian times, we would shield children from the messy realities of birth. But we would pull them in as little helpers when people were dying. As we cared for our dying, even our children would get a cool cloth and help. Whereas now, it’s kind of the opposite. Siblings will be there at a birth, but they are often not allowed to go to funerals.

I’m wondering how, if at all, has the pandemic shifted the conversation and the public’s approach to death?

Ovenell: I think it has been good in some regards, and in others, I have been told flat out it’s been too hard a time. We can’t engage in this conversation right now because everybody’s too distraught. I’ve also been told the exact opposite: “We need this more than ever now,” because people don’t know how to deal with [death].

Lazar: I agree. I don’t think we have the numbers or statistics to say whether this opened up our dialogue more or not, but it’s hard for us to know anecdotally.

It’s a nice segue to what’s going to happen, or what’s happening, with baby boomers. [The pandemic] has almost been like a dress rehearsal. Now we’re going to have people dying of all sorts of different causes, not just COVID-19…. We’re going to have way more deaths than we used to, and because they are boomers, they may want to die differently. For many that might be dying naturally, which means dying at home, being buried in a “green” cemetery, or something else.

You have both been in this space for years. In your professional practices, what gaps have you noticed in your discussions with health-care workers, or funeral directors, that you hope to change in your workshops?

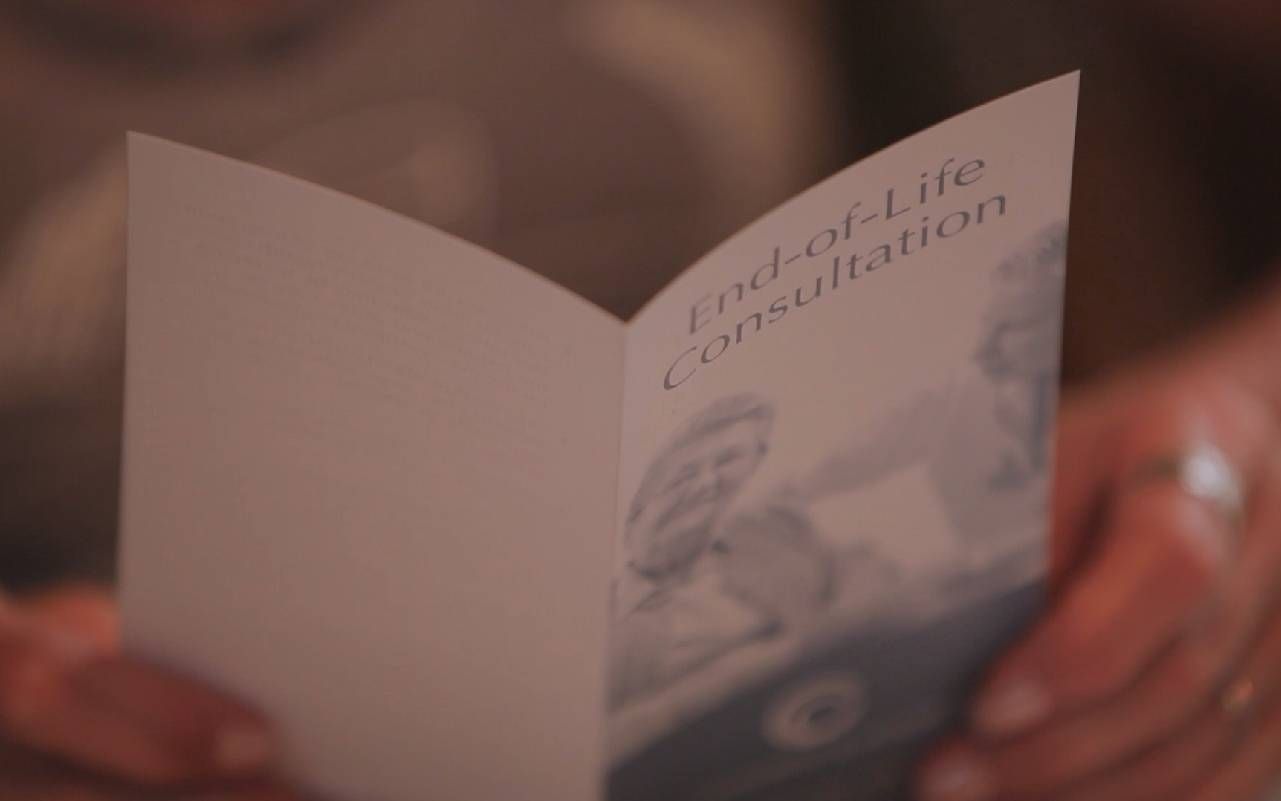

Lazar: One thing that bugs me is that there’s been an effort among public institutions to get people to do their end-of-life planning, or their advanced care planning as it’s called. They have all these forms online you fill out. Where they fall short is they make the assumption that people already know what they want, what’s important and what their values are.

So a lot of people get this free material, they might go to a free presentation, and they get the form and they’re like, “I don’t know how to fill this out because I don’t know what to say.” So that’s where Willow comes in. We’re heart-centered and inquiry-based.

Ovenell: In our strained and taxed health-care system right now, there is so little time for meaningful discussion and understanding. We have all these things that are like “tick this box, which box do you fit into?”

Lazar: I thought you were going to get into this, Christa, but the funeral industry itself. Most funeral homes are owned by like two companies?

Ovenell: In Canada, we have two major companies [Service Corporation International and Arbor Memorial Inc.] that own virtually all of the funeral homes. It’s good for them if people don’t know what is happening until death occurs.

Why is that?

Ovenell: Because then they’re the experts. Then they can say, “here’s what I think you should do.” This is not my analogy, this came from a writer named David Lynch, but he said imagine going into a car dealership, walking in, taking out your wallet and saying, “I need a car.”

What should I get? How much will it cost? There is no other thing that we ever meet in our lives that we would go into with as little preparation as our actual death. That is one thing that we all do.

What do you hope people take away from these sessions?

Ovenell: Life changing shit.

Lazar: I don’t really have to hope because I’ve done enough [sessions in the past] to know what they take away.

They, first of all, are inspired and empowered to start doing some planning and having conversations. To me, the best gift they can do is to start talking about this stuff with people in their circles: their brothers, their sisters, their families, their communities.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!