When I lost my brother David, I did not know how to grieve. Not because I lacked experience, but because suicide obliterates the rituals we have built around death.

By Adam Mansbach

We have just lived through a year that burned ritual to the ground — both the rituals of life and the rituals of death. All of us who have lost someone have had to contend with the partial or total suspension of the comforts to which we might have looked. We are not able to cry together, nor crowd a house with food and bodies. Perhaps we have been denied even the chance to bear witness to the jolting finality of burial. And so we may find that our grief cannot run its course — that it is unable to find its way back to the ocean, absent the normal waterways.

Ten years ago, when I lost my brother David, I did not know how to grieve. Not because I lacked experience, but because suicide obliterates the rituals we have built around death. How do you celebrate a life when the person who lived it contends, as David did in the note he left behind, that he had always wanted to be dead? How do you mourn when the death has been fought for — sought, with the same fervor that most of us seek to continue living?

When I try to talk about it, suicide defies me. I have learned that it cannot be grafted onto other conversations. Even discussions of death, of depression, provide not a means of ingress but a reminder that there are no bridges to this island. You must swim. The few times I have done so, I have been a little drunk, and hours into a first conversation with someone I know I want to keep. A sense that I am being dishonest takes hold of me — that everything is false until I bare this wound. I grow impatient to find a way, bore open a point of entry, my heart throwing off sparks as if I were working up the courage to declare my love.

But once I speak it, I must contend with what it feels like to recite a narrative I have whittled down from something incomprehensible to a set of talking points. It feels obscurely disrespectful, to speak as if I understand. My brother bought an expensive skateboard that did not arrive on his doorstep until after he was gone; he was planning to live and planning to die at the same time. It was not an either/or but a both at once — no more a paradox than a train station with two sets of tracks running in opposite directions. I can write these words, shape this idea into a metaphor, but I don’t truly understand it at all.

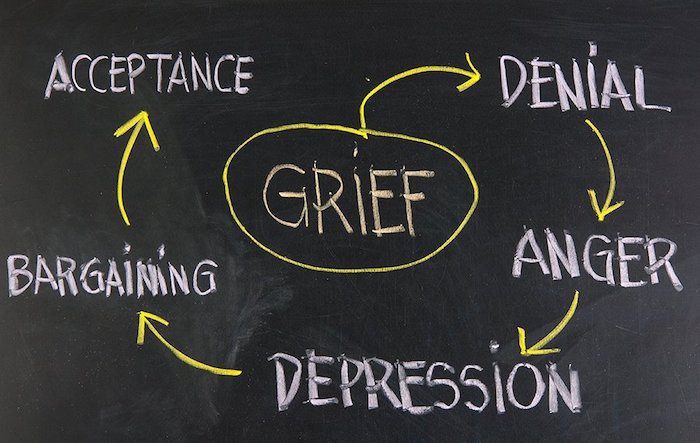

I wish I could say that I learned to be gentle with myself when I lost David and realized that I had no means of finding peace. But I was not. I tried to force myself, at every turn — to cry when I couldn’t but felt I should, to let go of what I didn’t actually want to relinquish, to hold onto things that burned. I tried to write about him almost immediately, and castigated myself when no words came.

It took me nine years to find the language I was looking for — not a language that alleviated my grief, but one that contained it. It came suddenly, the way they say grace does. The week David would have turned 40, I began to write very fast, with an intuition about what came next and how disparate ideas connected that I trusted entirely — even or perhaps especially when it meant I was putting forth a notion only to question or disavow or undercut it.

I knew it was a ritual, even if I did not know whether a ritual was meant to fill the hole left by the loss, or deepen it until I could crawl out the other side. I would not say I found closure, as some people have asked. That word is loaded and mysterious to me. But I did find something, or perhaps something found me.

It was David’s story; it was my own. I could not tell it until his death had receded enough for me to see the whole thing at once, and until I realized that it was OK, was necessary, for the particles of my loss to float in solution, unreconciled, suspended like judgment. That if all I did was stare at them the way I might the tank of undulating jellyfish at the aquarium — which I also cannot understand, but do not seek to — that would be enough.

I think about this now, at a time when so many of the rituals that have guided and succored us are trapped on the other side of the glass. What can we do, when what we need cannot be accessed, or simply does not exist? Perhaps we can trust ourselves to intuit and then invent the things we need — to become the rituals that will sustain us.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!