By Susanne Norris

When it comes to casual conversation, death understandably very rarely comes up as a subject that we jump at the chance of openly discussing.

Yet, it appears the coronavirus pandemic has made us all more aware of our own mortality and the mortality of those around us. Research by Dying Matters, a campaign group working to create an open culture around death and dying, found that nearly a quarter of UK adults (24%) say that the pandemic has made them more likely to have casual conversations with family and friends about preferences around their death.

While adults are potentially seeing the pandemic as a way to be more open about death, be that from coronavirus or other illnesses, one group is continually overlooked: children. Figures from Child Bereavement UK show that a child loses a parent every 22 minutes in the UK, equating to around 111 children being bereaved of a parent every single day.

During the pandemic and beyond, children have not just lost parents; they are also having to deal with grandparents, family friends, teachers and even siblings dying. Campaign groups and charities are working to help identify bereaved children and offer them the support they need, whether the bereavement is due to coronavirus or any other type of illness or injury. It’s now becoming apparent that we need a shift in public discourse, education systems and possibly even legislation in order to help bereaved children feel acknowledged and safe.

The current situation

The Childhood Bereavement Network analyses data from sources like the Office for National Statistics and uses its own research to estimate that 1 in 29 five to 16-year-olds has been bereaved of a parent or sibling – equating to a child in every average school class. “Unfortunately, there are no official figures on how many children are bereaved of a parent,” says Di Stubbs, a bereavement practitioner for charity Winston’s Wish. “A study has shown that 78% of children in the UK say they have experienced a ‘significant bereavement,’ showing that our children are very aware and affected by the mortality of those around them.”

Charities like Winston’s Wish were seeing many children before the pandemic to help support them through bereavements, alongside working with adults who know bereaved children to offer advice on how to best help young people during periods of grief. While children were facing countless bereavements before coronavirus, the pandemic has undoubtedly exacerbated the situation. “COVID emphasised our natural assumptions,” says Di. “The children we work with fall into many different groups. We are dealing with children who have been bereaved due to coronavirus. We are also dealing with children who have experienced a loved one die due to other reasons over lockdown, as the same amount of people are still dying from health conditions like heart attacks and strokes.”

There’s also another group of children that is now finding grief to be an issue. “Children who were bereaved before the pandemic are now finding that the current situation has really highlighted these intense emotions,” explains Di. “Suddenly, everyone is talking about death and bereavement all the time. Even for children who are not grieving, many have been quite suddenly exposed to the fragility of life and are having to respond to a new world.”

Navigating a new world

Coronavirus, and the lockdowns implemented to curb the spread of the disease, have caused confusion for many children around dying. “All of the rituals surrounding death, like funerals, were suddenly not there anymore,” says Di Stubbs. “We saw extremely sad situations, like shielding grandparents trying to comfort children over the death of a parent, whose only option was to do this through a window as no contact was allowed.”

Roseleen Cowie, regional lead at charity Child Bereavement UK, echoes this sentiment. “The effects of the pandemic have caused further pain for children going through a bereavement,” she says. “Without the usual rituals, children cannot say goodbye when someone dies, which has added to the difficulty. This is superimposed on the grieving, resulting in an additional loss and some people expressing their grief more deeply than may have been expected.”

Shelley Gilbert MBE, founder of specialist bereavement service Grief Encounter, stresses the importance of supporting bereaved people during and after the pandemic. “COVID has stolen things away from most of us, some bigger than others,” she says. “If someone special dies for young people, they are gone forever, and we need to think about how we support children throughout this period.”

Understanding children’s grief

Children grieve in a similar way to adults, but with some noticeable differences. According to the experts, ‘puddle jumping’ is to be expected. “Puddle jumping is the process by which children move in and out of their grief,” explains Roseleen Cowie. “A child may be very upset one moment and perfectly alright the next. Being aware of that is really helpful for people, especially in schools, as you can then appreciate that this is the way that children grieve.”

Puddle jumping tends to be different to how adults experience dealing with grief. “Adults tend to wade through grief, but children do this much faster; cycling in and out of grief and oscillating much faster than adults,” Di Stubbs explains. However, in many ways, the features of grief in children and adults are very similar, if not the same. “We can’t expect children to grieve differently to adults,” says Di. “All that anyone can do when they are bereaved is experience whatever intense emotions they are feeling. Eventually, we all grow around grief, allowing ourselves to experience new adventures and have fun.”

Talking to children about death

Undoubtedly, the consensus from experts is that children need to talk about death. “We recommend people use words like ‘dying,’ ‘dead’ and ‘death’ around children so that they have a clear understanding of what this is, as they won’t understand euphemisms,” explains Roseleen Cowie. Di Stubbs notes that language is particularly important, as phrases like ‘heart attack’ won’t make sense to some children, who may instead become distressed at the thought of a loved one being attacked, rather than understanding this to be a medical term.

Another expert who stresses the importance of using the right language is Nima Patel. A qualified primary school teacher and conscious parenting coach, she began her business, Mindful Champs, to encourage the practice of mindfulness between parents and children. Her latest project, a grief journal for children, encourages them to express themselves in whatever ways they can after a bereavement. “In 2017, my father suddenly died,” Nima discloses. “Seeing people lose loved ones during the pandemic, I wanted to create a toolkit for children and young people that I never had,” she says.

Nima realised the importance of having honest and open dialogues with children around death by using language that they can understand. “Children will have so many questions around death, but adults often don’t know how to answer these,” she explains. “My aim is to help children develop language to express themselves, and encourage adults and children to voice their feelings. If emotions aren’t spoken about in the home on a daily basis, a lot of children don’t have the language needed for emotional events, like a bereavement.”

Many children may find they need professional support when they are bereaved, and adults and schools are able to refer children to charities like Child Bereavement UK, Grief Encounter and Winston’s Wish or to NHS services. The way in these organisations can support grieving children or adults who are concerned about bereaved children can take a multitude of forms, from offering helplines to one-on-one counselling sessions.

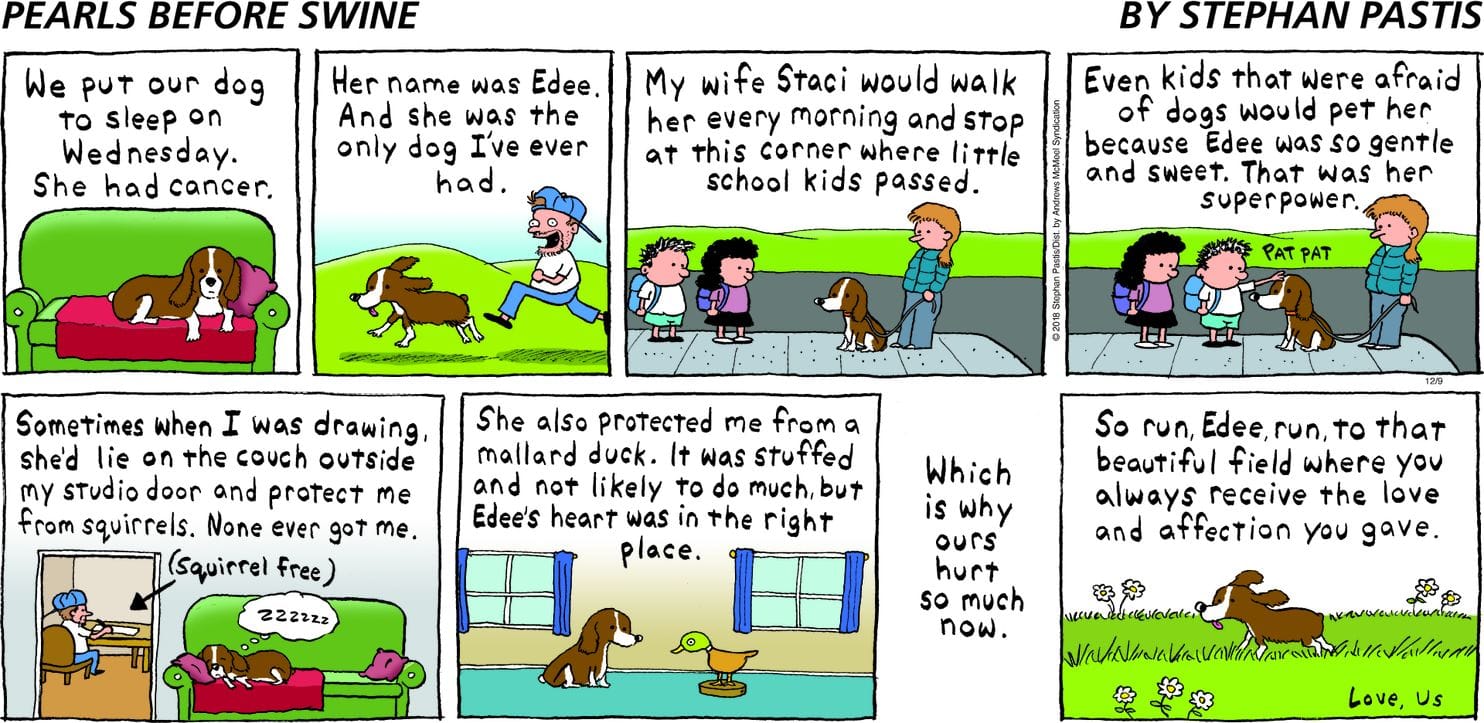

If you know a bereaved child, in addition to talking to them about their grief and emotions, another good way to help them express grief is through creativity. “Sometimes words are not enough to express our grief and this is where creativity comes in,” explains Shelley Gilbert MBE. “Being bereaved often means you haven’t the words to describe what you’re thinking or feeling. Old words have no meaning or take on new meanings and you’re learning words you’ve never heard before. Following the loss of someone special, we need a new language of grief.”

Creativity can come in many forms when expressing grief. Winston’s Wish encourages children to make memory jars or emotional first-aid kits, while there are also resources out there made specifically for grieving children, like Nima Patel’s Mindful Champs Grieving Journal. “We encourage activities like memory jars, flower releasing ceremonies and memorial trees in the journal to help children express their grief however they wish, be that verbal or non-verbal,” says Nima. Di Stubbs also recommends that books can be a great resource for children, including I Miss You: A First Look at Death and Goodbye Mousie to explain death to young children and Straight Talk about Death for Teenagers: How to Cope with Losing Someone You Love for teenagers. A further reading list is available at Winston’s Wish.

Assisting children with learning disabilities

For any child, dealing with grief can be tough, frightening and confusing. For children with learning disabilities, who may have acute difficulties expressing themselves, this can be a particularly hard time, especially during the pandemic. “We can’t emphasise enough the huge impact that the pandemic has had on children with learning disabilities,” says Tracey Hartley-Smith, a learning disability nurse and clinical lead at Cheshire and Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. “Coronavirus has impacted children’s opportunities for developing their social and communication skills hugely. We’ve seen through our work and heard from parents, carers and colleagues that children with learning disabilities have experienced heightened anxiety during this time.”

Tracey and her colleague, Dr. Jacqui Wood, a clinical psychologist at Cheshire and Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, have continued working with children with learning disabilities throughout the pandemic, including supporting them through grief and bereavement. “We encourage everyone interacting with a bereaved child to use the same, simple phrases when talking about death, as repetition is so important for consistency,” says Jacqui. “Visual aids, such as pictures or symbols, can often be helpful for sharing information with non-verbal young people, and helping them to express themselves,” she explains. Tracey adds that, as well as using the right language, “children with learning disabilities need to feel safe and loved, in whatever type of communication they use for this reassurance.”

Jacqui has recently published a guide specifically tailored for parents or carers of children with learning disabilities, which is accessible here. “Keep routines and boundaries, as they help establish predictability and security for children,” she advises. “Try to find opportunities to involve children in arrangements like funerals, to help develop their understanding of what has happened. Children with learning disabilities may also benefit from multi-sensory memory items, such as a piece of clothing from their loved one to touch and smell. This can help them learn to manage their expectations over time, so they adapt to remembering their loved one rather than physically seeing them,” she explains.

Jacqui also advises encouraging emotional regulation activities, be these for fun or relaxation. “Help children have fun during this difficult period by encouraging movement, whether that’s running around in the park or splashing about in the bath,” she says. “For calming sensory experiences, try dimming the lighting in your home, making a den to establish ‘quiet time’ or just comforting your child with regular hugs.”

Acknowledging and making memories

Above all, acknowledging that a child or teenager is grieving is incredibly important. Research by Dying Matters shows that 72% of those bereaved in the last five years would rather friends and colleagues said the wrong thing than nothing at all, and 62% say that being happy to listen was one of the top three most useful things someone did after they were bereaved.

“Above all, we should remember that love never dies,” says Shelley Gilbert MBE. “Lots of our work focuses on remembrance in difference ways, including remembering our loved ones as they were in the past and thinking about them in the present and future. When we make new memories, it can help to remember that our dead loved ones are with us in some way.”

When adults grieve, there is trauma and then a long road to acceptance. And, we should not assume that children and teenagers are any different. As Roseleen Cowie says: “When helping bereaved families, our ethos is that grief is a normal part of life: you can’t get over it or make it better, but you can learn to live with it.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!