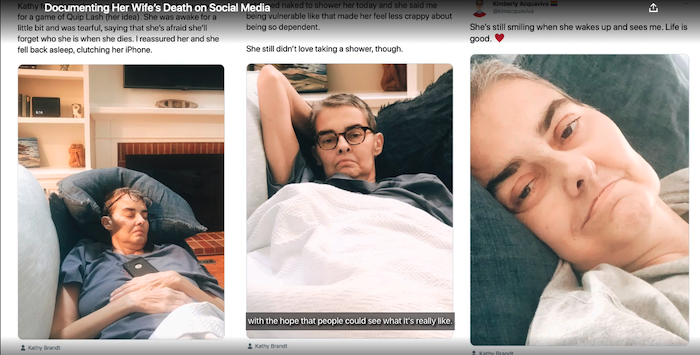

In “Documenting Death,” a couple who work in palliative care take to social media to share their experiences after one of them receives a terminal diagnosis.

Complete Article And Video ↪HERE↩!

The Amateur's Guide To Death & Dying

Enhancing Life Near Death

Complete Article And Video ↪HERE↩!

Changes do occur in many aspects of relationships between the affected person and his or her caregiver during the course of the disease. These changes, however, do not diminish a person’s need for love and affection.

The loss of companionship is perhaps the initial beginning of relationship changes. The caregiver, now assuming a caregiver role, misses the opportunities for intellectual conversation and misses that person who was a “sounding board” for any problems that arose or decisions that had to be made.

The person affected may have always taken care of the family’s finances, but as the disease progresses, the caregiver must learn to make all the decisions of financial and legal matters, which can be challenging and difficult for someone already overwhelmed. Some caregivers get help from a financial adviser to assist in these meticulous tasks and decisions.

Alzheimer’s disease affects the sexual relationship between partners, too. The affected person may exhibit hypersexuality, putting demands on the caregiver and, at times, be overly affectionate at the wrong time or place. On the other hand, interest in sex may wane or decrease, and the caregiver soon misses that loss of intimacy. Yet, there can be intimacy without sexual relations. Cuddling, dancing, enjoying moments together holding hands, gentle massages are all ways of experiencing intimacy and ways to satisfy the needs of both the affected person and the caregiver.

The caregiver should try to be honest with his or her feelings regarding these relationship changes and to find ways to express them, whether it be through talking with close friends or by joining a support group.

Relationships with family and friends sometimes change drastically. Often family and friends are intimidated or are uneasy around someone with Alzheimer’s. They don’t know how to communicate with them and may feel threatened by his or her behaviors.

The caregiver can become just as isolated as his or her loved one. The caregiver should contact family and friends and share the loved one’s condition, with tips on communicating and ways they can visit in a nonthreatening manner.

The caregiver should encourage visits with family and friends for the sake of their loved one and themselves.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

I never knew your mental health could so heavily dictate how you feel about sex. When I was a teenager and in my early 20s, I never thought my sex drive could be “turned off.” I had a constant interest and energy and was always finding new ways to get high off of love. Fast-forward to just a few years later, and I can’t seem to get high off of anything. The confidence I once felt about putting myself out there has been replaced with fear, and the fun and excitement I once felt about dating has been replaced with me deleting dating apps just to avoid people. A lot of this has to do with the grief I’ve felt after the tragic loss of my mother in 2018. Since then, I can count on less than one hand the people I’ve sought sexual comfort in. Nothing and nobody could make me feel better.

When I lost my mom, I lost something I was able to attach myself to. I constantly found myself in this battle between “Am I getting over this too fast?” and “Am I not moving on fast enough?” While some can work through this by finding love and comfort in someone else’s arms, there are many others, like me, who can’t seem to get far enough away from potential partners.

Yes, I miss connection, intimacy, and touch, but until I get the green light from my body and mind, I will continue to protect my sexual well-being.

After a loss, it’s easy to feel like you’re not enough. You become a different person from who you were before your grief. You no longer see yourself as you once were, and trying to navigate this new normal is incredibly challenging. At least that’s what happened to me.

My depression and anxiety kicked in almost as soon as my grief did. Because depression can change the chemical makeup in our brains, people dealing with it can be less likely to have a libido. The tiredness that comes along with it can take away all energy for intimacy. And because depression is a lonely experience, I’ve found it nearly impossible to connect with people in that way. Grief can also make people feel like they’ve lost their sense of control and make them worry about what else they could lose in the future. You can become so focused on trying to move forward that you’re blind to things that might make you feel good. And many times you don’t think you deserve to feel good because you’ve lost something that can never be replaced. This is even worse when you’re in the denial phase of your grief.

It’s been two years since my mom passed, and I’m still working through my grief.

I always fear that my mom is looking at all of the decisions I’m making and shaking her head at them. That shame sometimes prevents me from wanting to be intimate with someone. I’ve had a hard time reconciling with the fact that when someone’s gone, they’re gone and not watching my every move. I know I should be thinking that my mother would be happy that I’m trying to move on and get back to my new normal — which includes having a healthy sex life — but I’m just not there yet.

During sex, we open ourselves up on a physical level while also being extremely vulnerable on an energetic and emotional level. When you’re depressed, anxious, and grieving, it’s hard to open up at all. From my experience, it’s almost harder to have a casual hookup with someone you don’t know much about. Although some may say the opposite, I think waiting to have sex with someone you’re truly comfortable with is better than trying to fill a void.

I know the more I practice being present with myself and my feelings, the better my emotional state will be. Introducing more self-care routines like exercise, rest, and moments to myself will help with the healing process. But one thing I won’t do is blame myself or tell myself I’m unlovable. Yes, I miss connection, intimacy, and touch, but until I get the green light from my body and mind, I will continue to protect my sexual well-being. I won’t rush it.

Grief is not a numbers game. Just because there are different steps of grief doesn’t mean that you take all of them in order or are simply done after a set amount of time. My grief is something that I’ll have with me forever. How I choose to let it affect me, though, is up to me. And I’m still figuring that out.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Palliative, or end of life care can help people with terminal conditions, such as cancer, live as well as possible for as long as possible – and allow them to die with dignity. But end of life care is not a straightforward process. And for patients from the LGBT community, the process presents a whole host of barriers that they and their families may face.

Not only do many people from the LGBT community face difficulties accessing high-quality end-of-life care, they also may face issues with their care. This may sometimes be because of ignorance and prejudice against them during pre-hospital admission. It may also be due to poor communication between patients and care providers about treatment plans, judgement by staff about a patient’s family or relationships, and a failure to properly support the spiritual needs of the patient.

Many have also experienced victimisation, discrimination and personal hardship as a result of their sexual identity throughout their life, and may feel that telling a healthcare professional about their sexual identity would change their interactions or quality of treatment.

Staff may also be unaware of an LGBT patient’s particular needs or how to meet them. For example, patients who have undergone gender reassignment may have been married previously in their former gender. They might have children and grandchildren. Dealing with current partners, spouses, former spouses and children during end of life care takes particular skills, which requires specialist training. As many in palliative care want to be surrounded by loved ones, healthcare workers need to be trained to deal with these types of situations.

Many LGBT people may also hide their relationships, meaning that healthcare workers may exclude key individuals from their loved one’s end of life care. Other factors that can impact end of life care include whether an LGBT person lives alone, if they’re socially isolated, and if they face barriers to services or lack consultation. Ageism, and past negative experiences relating to their sexual orientation or gender identity, might also impact the care they receive.

Bereaved LGBT partners and spouses have also been found to experience less support during the death of their loved one. They complained of being shut out of the care process and ignored.

Healthcare professionals also aren’t typically trained to address the specific needs of the LGBT community when it comes to end-of-life care. These needs will include the need for confidentiality and communication from healthcare providers that is sensitive to their sexuality and preferences. Many LGBT people may also feel too vulnerable to disclose their sexual identity while receiving this type of care, which may make their final months lonely.

Research shows that LGBT people already have lower health outcomes, partly because of ignorance of LGBT issues among healthcare practitioners. For example, they may not receive routine cancer screenings, and may not be able to access adequate healthcare services.

Sexual orientation and gender identity are also both key areas where inequality and discrimination can occur in end of life care. Poor training has been highlighted as one cause.

But many of the shortfalls faced by the LGBT community during palliative care are prohibited and protected by the Human Rights Act 1998. Article three states that no one shall be subject to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, while article eight protects a person’s right to privacy, respect for their sexual identity and the right to control information about their private life.

The issues addressed in articles three and eight have been interpreted by the courts as including how a person plans their end of life care. This means there could potentially be legal redress for any person who feels that their wishes and feelings relating to end of life care aren’t being taken into account by the healthcare workers looking after them.

There are two particular aspects of good end of life care that many LGBT people find are most important to them. First, they want their care to focus on their individual needs. Second, they want their partner to be accepted.

Currently, there are recommendations in place for caring for those from the LGBT community in palliative care. In order to ensure that LGBT people receive the best end of life care going forward, it will be important for healthcare workers to have better training.

Better training will ensure they can communicate properly with LGBT people about their needs and understand their situation. Training will need to include understanding equality, diversity and confidentiality, as well as understanding the unique issues LGBT people face and how this impacts end of life care. Staff or other residents should also report any discrimination to prevent it from continuing in the future.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

“DYING TRANS: PRESERVING IDENTITY IN DEATH” http://www.orderofthegooddeath.com/dy…

“The Supreme Court is finally taking on trans rights. Here’s the woman who started it all.” https://www.vox.com/latest-news/2019/…

“R.G. & G.R. HARRIS FUNERAL HOMES V EEOC & AIMEE STEPHENS” https://www.aclu.org/cases/rg-gr-harr…

“A transgender woman wrote a letter to her boss. It led to her firing — and a trip to the Supreme Court.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation…

“Transgender woman dies suddenly, presented at funeral in open casket as a man” https://www.miamiherald.com/news/loca…

“Transgender People Are Misgendered, Even in Death” https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/ex…

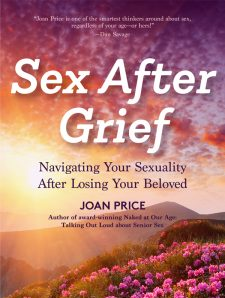

In the difficult months after her husband Robert’s death, Joan Price found herself confronted with a veritable mountain of self-help books about grieving. None of them touched on the subject that would preoccupy her for the coming decade: What about sex?

Price is a sex educator, with an emphasis on older people, so perhaps she was primed for this question. But others have noticed this glaring absence in the literature of grieving, too. “The unspoken message, as I received it: keep your mouths shut about sex,” writes Alice Radosh in Modern Loss: Candid Conversations about Grief. “I turned to self-help books for widows, and found that there, too, discussions about sex were pretty much nonexistent.”

Price is used to older people’s sex lives being ignored. “I call it the ‘ick factor’ our society has,” she tells me, when I meet her near her Northern California home. “Eww: old people having sex, wrinkly sex!” she giggles to herself. Price says this ageist notion prevents older people from enjoying their sexuality, a vital part of being human, however old one is.

“We have internalized this ‘ick factor,’” she says. “We see ourselves as undesirable, as over the hill. We see ourselves as needing to say goodbye to sex when things don’t work the way they used to.” And therein lies Joan Price’s mission: to “talk out loud about senior sex,” even in life’s hardest moments. Her new book, Sex After Grief: Navigating Your Sexuality After Losing Your Beloved, seeks to fill the void in grieving literature.

Seeing Price now, you’d have little external indication that she spent years struggling with the weight of bereavement. The first word I think of when I meet her is “spritely.” Just shy of five feet tall, Price has a twinkle of a laugh that frequently punctuates our conversation, and a playful, vibrant sense of fashion. Her fingernails are painted the purple of grape candy, and she’s wearing dangly earrings of bright, geometric shapes.

At 76, her calendar is filled with giving talks on sexuality, reviewing sex toys for her blog and teaching a bi-weekly line dancing class at a local fitness center.

It was at that line dancing class that a couple of decades ago, Price met the man who would become her husband, an artist named Robert Rice. “He walked in, and I forgot how to breathe,” she tells me. “As soon as he started moving his hips, I lost my place in the dance I was teaching. I just couldn’t take my eyes off this man.”

Price was in her late fifties at the time, already in her second career, having left a job teaching high school for one writing about fitness. The last thing she expected was a life-changing love affair. The blossoming of her romance with Robert nurtured yet another new area of work for her: writing about sex.

“It was an amazing revelation because sex was fantastic with him, but it was not the same as younger-age sex,” she says. “There was much slower arousal… It just took a lot of earnest effort on his part… It was very different. But I was feeling that sex at our age was better, that that wasn’t a defect.”

She wrote a first book, Better Than I Ever Expected: Straight Talk About Sex After Sixty, celebrating that discovery. A second book, Naked at Our Age, sought to answer the questions and resolve problems that older people were experiencing in their sex lives, from what position to use when pained by arthritic joints to a definition of sex that didn’t center orgasm as the only worthwhile goal.

It was when she was just starting to write that book, that Rice was diagnosed with cancer. “I put a hold on everything,” she says. When he died in 2008, Price was completely undone.

“I thought because I knew Robert was dying, that I was getting prepared for it,” she says. “You can’t prepare for that. You cannot know how that bludgeons your brain and your heart. It was all I could do to remember to brush my teeth.”

She would cry all day, pull herself together to drive to the health club, and teach her line-dancing class. Then she’d resume crying in the locker room, and weep all the way home.

For months, Price writes, her sexuality was dormant. That period of deep grief was followed by the fits and starts of trying to find her way into a new version of her romantic and sex life. This became the fodder for Sex After Grief. Price wanted to give other grievers a manual for navigating the tangle of experiences they might have.

“Some people feel frenetic sexual energy and yearn for a sexual outlet right away,” she writes. “Some start dating immediately, some gradually, some not ever. Some withdraw from sexual possibility. Some share their bodies but not their hearts. Many give themselves sexual release to the fantasy of their lost loved one.” All of these different responses are normal, Price insists. There isn’t one right way to move through it.

“Some people feel frenetic sexual energy and yearn for a sexual outlet right away,” she writes. “Some start dating immediately, some gradually, some not ever. Some withdraw from sexual possibility. Some share their bodies but not their hearts. Many give themselves sexual release to the fantasy of their lost loved one.” All of these different responses are normal, Price insists. There isn’t one right way to move through it.

In keeping with the absence of sex in the literature of grief, there’s been very little scientific research into it, either. One of the few studies of “sexual bereavement,” as its authors term it, came out in 2017 in the journal Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters.

The study revealed that 72% of respondents (who were women age 55 and older) anticipated missing sex with their partner, and that 67% would want to initiate a discussion with a friend about it. But there was also a disconnect: 67% reported that it’d be difficult to discuss sex with a friend whose partner had died, attributing that difficulty to embarrassment.

Price addresses that embarrassment head-on in her new book. She dives into the thicket of myths and taboos of sexuality after loss — from questions of loyalty to one’s deceased partner to how long grieving should last — offering readers scripts for how to respond to advice that doesn’t resonate with their experience.

“Because in the moment, you know, you think, ‘Oh my gosh, am I supposed to take that on?’” she tells me. “’Am I supposed to be embarrassed? Am I supposed to be shamed? Am I doing the wrong thing? Am I doing grief wrong?’ You’re not doing grief wrong.”

Price’s message is clear: our sex lives don’t have to end as we get older, or when our partner dies. Whether we’re having partnered sex or not, she advocates, our sexual selves continue.

The book delves into the practicalities of solo sex, as well as various approaches for dating and different relationship models for older people who may not want to follow a marriage with another long-term relationship, but still want to remain sexually active.

Price is an advocate for thinking about a trusted “friends-with-benefits” arrangement, and quotes a 2013 “Singles in America” study from Match.com that revealed 58% of single men and 50% of single women had had one, including one in three people in their 70s.

She writes about how she kept two journals: one to chronicle the difficulties of grieving and another to record treasured memories that kept her husband alive for her. She writes about feeling out her own personal timetable for when to start having sex again, and with whom.

Price had some false starts, which she found instructive. “If you don’t know if you’re ready to date, it’s okay to try it and then put dating on hold if it feels wrong,” she writes. “You’re not making any kind of commitment you can’t reverse. The same is true for sex. You can explore, then change your mind at any point.”

Price’s own story is one of persistence, of refusing to allow society’s derision of aging bodies to stop her from enjoying her own and of not allowing even the tremendous loss of her loving partner to stop her from engaging with her sexual self. The story, she says, is always continuing.

In the past couple of years, it’s had yet another twist. Price put up a profile on OKCupid, and, after more than a few disappointing dates, she met a retired anthropologist named Mac Marshall who lived nearby. Marshall had recently lost his long-term partner to illness. They shared their grief stories amidst a flurry of other information on their early dates, and in emails.

Price dedicates Sex After Grief both to her husband Robert, “who lives in my memory and in my heart,” and to Mac, “who shows me that joy is possible after grief.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The day after I saw my dad for what would turn out to be the last time, I surprised myself and told someone I’m queer.

It was first-year move-in day at college. I had just left behind the breezes of Southern California for the 90-degree temperatures and relentless humidity of late August in New York City. Soaked in sweat but giddy, I took a break from sorting out storage bins and dorm décor to sit on the floor and get to know my three new roommates. Early into our conversation, I suddenly said, “I’m pretty sure I’m bisexual.”

I remember inelegantly shoving it into our early introductions, unprompted. To my roommates, I’m sure this brief declaration was as laid-back as the tie-dyed crop top I was wearing that day. (It said “stay rad” across it. I know.) But for me, it sparked a moment of exhilarated panic as my mother and aunt—both of whom did not know about my recent self-discovery—returned to my room. As the two of them struggled to help me organize my life in our itty-bitty shared space, I whispered from the floor: “Don’t mention what I said earlier. I’m not out to them.”

Actually, I wasn’t out to anyone, except a few close friends. My mom and sisters were largely progressive, but I had also been raised in a Catholic home and attended Catholic school through eighth grade. My father, meanwhile, was a kind of atheist, nonvoting libertarian, often hellbent on defending his own political apathy. In one of the very last conversations I ever had with him, he kept trying to press my buttons. As he drove my mother and me to the airport to begin my college journey, he shared tongue-in-cheek admiration for “our future female president”: Carly Fiorina. (This was 2015.) He laughed and I rolled my eyes, but it felt clear I couldn’t tell him what I was realizing about myself.

In the latter half of my high school years, I hadn’t quite come out to myself either. I consistently explored the now virtually nonexistent corners of queer Tumblr. (Remember #girlskissing? No?) After I used every silly, drunken senior-year Model U.N. party as an opportunity to kiss my girlfriends, my own sexual fluidity started to become a little clearer. I had come to see historically women’s colleges as queer havens (thanks, also, to Tumblr), so I chose one for myself. I decided that a journey of coming out could be safely relegated to college, and maybe—just maybe—if I got a girlfriend, I would have reasonable enough “proof” to open the conversation at home, with my mom and, somehow, my dad.

Less than two weeks after I arrived at my dorm room, my dad died of a sudden heart attack. I had just finished my first week of classes.

My immediate grief saw me fluctuating between long days in bed and spurts of typical freshman social energy. I felt most alive after campus activities related to the queer community. I joined a Facebook group called “HELLA GAY MOVIE NIGHTS.” I attended monthly LGBTQ dance parties. I performed in our musical theater society’s Rocky Horror Picture Show shadow cast.

I emerged more fully out of the closet, but I still hadn’t come out to family. In fact, I felt like I was living a double life: one part of me idle and in mourning and the other, out. The thrill of that felt so distinct from my grieving self that it was almost as if the openly queer part of me was unburdened by my loss—so separate and distinct that my old life, and its sudden tragedy, began to feel less real.

Returning home for breaks during the school year shattered that illusion. My grief ruled me. I came to a realization: While I wanted to share my new self, my new life, with my mom and sisters, I felt a devastating relief that I wouldn’t ever have to come out to my father. I had no way of knowing how he would react, but I took comfort in knowing I’d never have to face even the slightest disapproval, criticism, or judgment from him. It was a dark kind of consolation.

Then I met my first girlfriend. I fell in love with her. I envisioned a future with her. In a few clumsy, emotional conversations, I finally shared my secret—and my relationship—with my family. They were awkward, but ultimately happy to embrace this part of me.

When you lose a parent in your teens, you immediately imagine all the milestones you’ll hit without them: graduation, a first job, a wedding, and a family of your own. But I also started to realize that my father might not even recognize me anymore, not only because of how I had aged but also because of who I’d become.

I began to have recurring dreams where he came back to life and I was tasked with welcoming him back to our world, back to our family, and to the new me. I would update him on all he had missed. It took this chimerical notion to make me rethink my relief: If any of these dreams ever took place on my wedding day, it’s possible that my father would look right past me, because I might be next to a woman.

Nearly a year later, that realization launched a kind of second mourning. I lost him first, then, later, lost the opportunity for him to ever know who I am. To know me at my happiest. I felt intense guilt and shame about the comfort I had initially taken in avoiding the conversation.

Around that time, I realized something else. I wanted to tell my most elderly family members who I was before they were gone too. This presented obstacles. My living grandfather is an octogenarian from the Middle East. My living grandmother and her sister are 92 and 100 years old, respectively. These two women live in my family’s home. They are all deeply Catholic.

Last May, my grandfather was set to visit New York City for my commencement. A few weeks prior to the ceremony, my mother mentioned to me over the phone that if my then-girlfriend would be celebrating with us, I owed him a conversation before his trip “to avoid any surprises.” Before I could gather the will, my girlfriend and I broke up, and my grandfather’s lymphoma kept him in California.

Soon it’ll have been another year since then. I still haven’t come out to any of them. I’ve worried that I’ll experience the same parallel grief when their times come. After college, I stayed on the East Coast, so perhaps I really fear being absent in the last years of their lives. Perhaps I don’t want to trouble them with an exasperated conversation in their old age. Perhaps I want to spare myself the pain of rejection.

Another part of me believes they already know. They don’t comment on my short haircut or my unshaven body hair when I’m home, and they’ve stopped asking me about my romantic prospects. Maybe there’s a mutual, unspoken understanding between all of us.

When I think back on the dark nights scrolling through Tumblr or that steamy move-in day with my quiet coming out, I look fondly on a person who was finally allowing herself to live the life she wanted. I don’t judge her for hiding before. I don’t scoff at her past fears. Instead, I respect her for waiting for the moment to be right for her.

More than a half-decade later, I’ve discovered a different side of that person. The side that accepts the person her father knew when he died. And the side that, when it comes to revealing her full self to the rest of her family’s elders, gives herself permission to be OK with what they may never know.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!