by Mariana Dale

[I]nside a medical care facility in central Phoenix there’s a small chapel with frosted glass windows.

On the wall there’s more than a dozen framed photos of smiling faces. These are the people who have passed on here; many were in the final stages of their life.

“They all brought their gifts to this world and they ended up in a place where they had no one,” said Lin Sue Cooney, Hospice of the Valley Community Engagement director. “It’s our collective responsibility as a community to make sure that they have dignity and comfort at the end of life.”

The medical care center Circle the City has 50 beds to care for the homeless, and several are reserved for hospice patients. Medicaid can pay for end-of life-care and even those who can’t pay anything are still treated.

The number of homeless older Americans is rising.

The state’s largest emergency shelter, Central Arizona Shelter Services, known as CASS, saw 423 clients over age 62 last year.

CEO Lisa Glow said the oldest, 89, came into the shelter pushing a walker. Her son was taking her pension and she was homeless.

“There’s vulnerability to fraud, vulnerability to disease, vulnerability to abuse and being taken advantage of,” Glow said. She said there aren’t enough resources at CASS or in the Valley to handle the predicted influx of older people who will end up on the streets and in poor health.

“Being an emergency shelter, people have to take care of their basic daily living needs,” Glow said.

Jesus Tovar, 67, was discharged from the hospital to Circle the City.

“Me sufre mucho en la calle, mucho frío, llueve, a veces no tienes que comer.” Tovar said he suffered a lot in the streets; it was cold, it rained and sometimes he didn’t have anything to eat. Tovar is diabetic and has problems with his lungs and heart.

His voice became thick with emotion when he talked about life on the street.

“Aquí tienes cama. Te dan tus medicinas.” Here there’s a bed, they give you your medicine. It’s like another family, Tovar said. “Aquí tiene como otro familia.”

Tovar is also working toward connecting with his own family through a social worker at the center.

“With that aging comes an inherent need for better end of life care and we have to be able to rise to that challenge,” said Brandon Clark, Circle the City CEO.

“When people come here on hospice they frequently have no one,” Clark said. “It’s rare they have no one when they leave this world.”

‘Pride almost killed me’

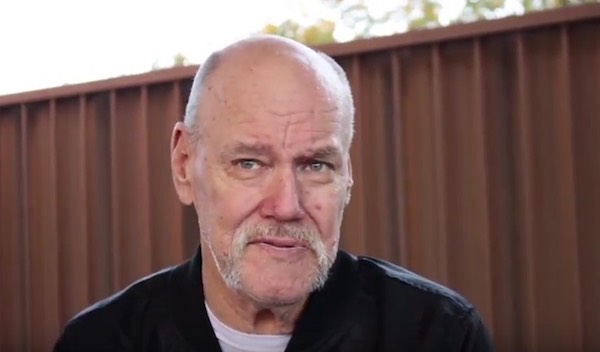

Almost everything James Martz is wearing from his UnderArmor sweatshirt to his tennis shoes is new, at least to him.

A chunky silver ring on his right hand is one of the only material possessions Martz still has from his “old life.” It represented his time as a member of the North American Hunting Club.

Martz can list the events that lead to rock bottom — drug use, an eviction, a pneumonia diagnosis that revealed lung cancer, chemotherapy.

“It would make me throw up, the other thing,” Martz said grimacing. “You didn’t want to eat. You wanted to sleep all the time.”

In September, Martz said his oncologist gave him six to nine months to live.

Around that time he was sleeping in his broken down 1993 Oldsmobile Cutlass in a strip mall parking lot in Mesa. Eventually police kicked him out after the center’s owner complained.

“I just grabbed my meds and anything essential and just walked off the property,” Martz said. He walked until the skin on his feet bubbled into blisters. A hospital covered the wounds with salve and discharged him.

“I got out of the hospital and I tried to get out of the wheelchair they wheeled me in and I couldn’t even stand up,” Martz said. Then he remembered he had a number for Hospice of the Valley.

“He was very sick, sad, uncertain of the future, some anxiety and I think he just didn’t know what was going to happen,” said Kim Despres, a program director at Circle the City where Martz ended up.

RELATED: KJZZ’s Special Series, Homeless In Plain Sight

Homeless people can recover there when they’re not sick enough to stay in a hospital, but not well enough to be on the streets.

It’s also one of the only places that provides end-of-life care for people who have nowhere else to go. James Martz had decided he was done with chemotherapy and entered hospice there.

Hospice of the Valley took care of 18,500 patients and family members last year. It’s just one of dozens of hospice organizations in the Valley.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!