Cruel to be kind: animal hospice gives pets better way to die

By

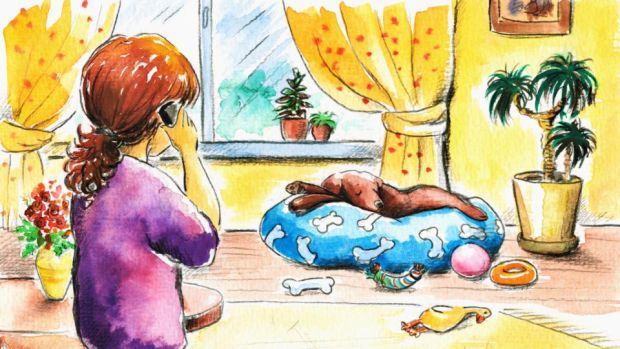

Nearly 14 years ago, my daughter and I were grieving the death of my mother, and it seemed nothing could lift our spirits. Then we got Fluffy, a bouncing bundle of gray and white puppy, and everything changed.

Fluffy kept us busy with pee pads and squeaky toys. She made us laugh in spite of our sadness, and the gray clouds of grief began to recede

Over the years, our 10lb fluff ball was a constant in our lives. We dressed her up in holiday sweaters, celebrated her birthdays and scolded her for sneaking food from the cat’s dish. But in recent weeks, as our walks slowed down and her naps grew longer, it became clear that our time together was limited. I hoped that in the end, Fluffy would have a natural death, drifting off to sleep for good on her favorite pillow

A natural death is what many of us hope for with our pets. They are members of our family, deeply enmeshed in our lives, and for many of us, thoughts of euthanasia seem unfathomable, so we cling to the notion that a natural death is desirable.

In most cases, a natural death, she said, means prolonged suffering

But my veterinarian said that my end-of-life scenario for my dog wasn’t realistic. In most cases, a natural death, she said, means prolonged suffering that we don’t always see, because dogs and cats are far more stoic than humans when it comes to pain.

Dr Alice Villalobos, an oncology veterinarian in California, said that many pet owners idealise a natural death without thinking about what a “natural” death really means. A frail animal, she noted, doesn’t linger very long in nature. “When animals were domesticated, they gave up that freedom to go under a bush and wait to die,” Villalobos said. “They become very quickly part of mother nature’s plan due to predators or the elements. And yet in our homes we protect them from everything so they can live a long time – and sometimes too long.”

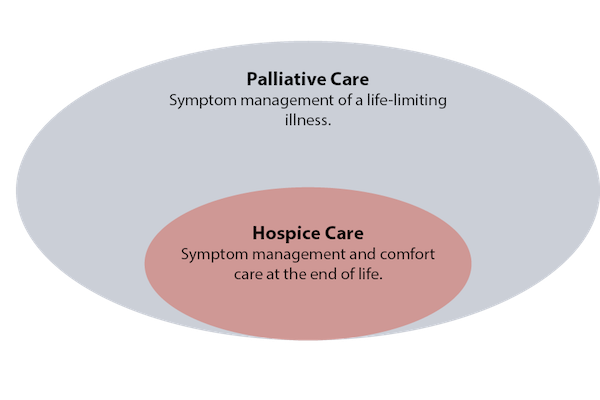

Villalobos has dedicated her career to helping pet owners navigate end-of-life issues. She created an animal hospice program she calls “pawspice.” She coined the name because she doesn’t want to confuse end-of-life care for animals with the choices we make for human hospice.

Her program is focused on extending a pet’s quality of life. That might mean treating a cancer “in kind and gentle ways,” she said. It can mean supportive care like giving fluids, oxygen or pain medication. In some cases, it might mean hand-feeding for frail pets or carrying an animal to a water dish or litter box. And finally, she said, it means a “well death.”

Villalobos has advocated what she calls “bond-centered euthanasia,” which allows the pet owner to be present and play a comforting role during the procedure. She has also championed sedation-first euthanasia, putting the animal into a gentle sleep before administering a lethal drug.

To help pet owners make decisions about end-of-life care, Villalobos developed a decision tool based on seven indicators. The scale is often called the HHHHHMM scale, based on the first letter of each indicator. On a scale of zero to 10, with zero being very poor and 10 being best, a pet owner is asked to rate the following:

HURT Is the pet’s pain successfully managed? Is it breathing with ease or distress?

HUNGER Is the pet eating enough? Does hand-feeding help?

HYDRATION Is the patient dehydrated?

HYGIENE Is the pet able to stay clean? Is it suffering from bed sores?

HAPPINESS Does the pet express joy and interest?

MOBILITY Can the patient get up without assistance? Is it stumbling?

MORE Does your pet have more good days than bad? Is a healthy human-animal bond still possible?

Villalobos said pet owners should talk to their vet about the ways they can improve a pet’s life in each category. When pet owners approach end of life this way, they are often surprised at how much they can do to improve a pet’s quality of life, she said.

By revisiting the scale frequently, pet owners can better assess the quality of the pet’s hospice care and gauge an animal’s decline. The goal should be to keep the total at 35 or higher. And as the numbers begin to decline below 35, the scale can be used to help a pet owner make a final decision about euthanasia.

“Natural death, as much as many people wish it would happen, may not be kind and may not be easy and may not be peaceful,” Villalobos said. “Most people would prefer to assure a peaceful passing. You’re just helping the pet separate from the pack just as he would have done in nature.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!