Not a day goes by that speakers of the Yoruba language do not make mention of death as both a phenomenon and a certainty.

By George Yancy

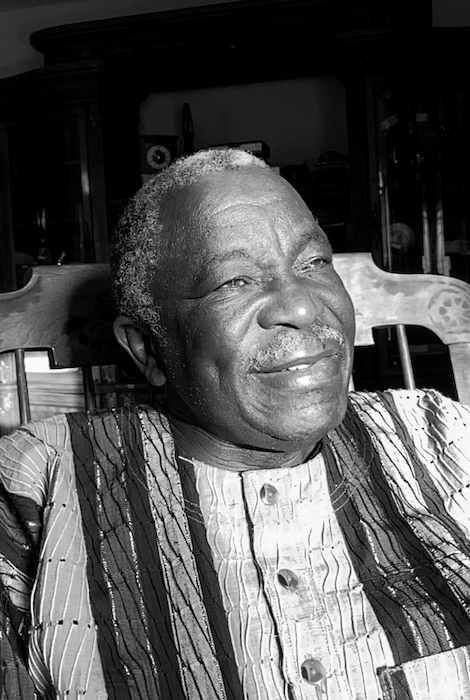

This month’s conversation in our series exploring religion and death is with Jacob Kehinde Olupona, a professor of African religious traditions at Harvard Divinity School. He is the author of “City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination” and “African Religions: A Very Short Introduction.” In this discussion we focused on the religious tradition of the Yoruba people. Previous interviews in this series — with scholars from the Buddhist, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Jain, Taoist and atheist traditions — can be found here. — George Yancy

George Yancy: Here in the West, where a few monotheistic religions dominate the culture, knowledge and understanding of Indigenous African religious practices is rare. Is Yoruba monotheistic or polytheistic? Or is it something else entirely?

Jacob Kehinde Olupona: Yoruba religion manifests elements of both. It differs from many world religions that define their cosmology primarily in theistic terms. Yoruba religion focuses on the lived religious experience of the people rather than on systematized beliefs and creeds as we see in other world religions such as Islam and Christianity. Yoruba religious traditions are woven around oral traditions and practices. The spiritual realm exists parallel to the human realm and it accommodates the Supreme Being, gods, ancestors and minor spiritual entities who interact with the human realm at different levels.

Central to the Yoruba religious worldview is the notion of (Ase), which Rowland Abiodun has characterized as “the empowered word that must come to pass,” “life force” and “energy” that regulates all movement and activity in the universe. Religious activities are mostly communal and are guided by specialists, custodians and leaders of the traditions: sacred kings, diviners, priests, priestesses and healers, all of whom are integral to maintaining the balance in the cosmos.

The Yoruba conceive the world as two halves of a gourd — the one we live in and the one where the deities and ancestors live. In between these two spheres, there are forces, mainly malevolent in nature (ajogun, or warriors), as Wande Abimbola calls them, who must be constantly placated, sometimes with sacrifices, to prevent them from wreaking havoc on earth. In short, human devotional practices play a central role in regulating the activities of ajogun and in keeping the Yoruba universe in equilibrium.

Yancy: In the West, Indigenous African religions are often dismissed as “primitive” or “superstitious” by those who don’t know them. Can you give readers unfamiliar with African religious traditions some sense of the history and complexity of the Yoruba people and their culture?

Olupona: The Yoruba people, who live primarily in southwest Nigeria, are one of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa. Yoruba people are also found in the Republic of Benin, Togo, Sierra Leone and several other countries. As a result of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, between the 16th and 19th centuries, a large number of Yoruba were taken to the Caribbean, North America and South America, where they had significant influence on the culture and religion of the New World.

Yancy: So in some sense, influences of Yoruba culture and sensibility are already here in the West, and have been for centuries. What about the main population in Nigeria?

Olupona: The origin of the Yoruba in Nigeria is slightly more complex. According to the Yoruba origin myth, the world was created in the sacred city of Ilé-Ifè, where the Yoruba civilization blossomed in the ninth century and grew to become one of the largest empires in West Africa. While the Yoruba Empire Oyo is now acknowledged as the source of the standard and contemporary Yoruba language, culture and value system, it is to Ilé-Ifè (the ancient and sacred city of the Yoruba) that scholars now believe all other Yoruba settlements owe their unrivaled urban culture and robust cosmopolitan city states. Other origin myths allude to Yoruba migration from distant places to their current homes, but that has not been substantiated by archaeology or in the Yoruba culture more broadly.

Yancy: How do Yoruba believers think about the reality and meaning of death?

Olupona: Death as a palpable force looms large in the Yoruba religious and social consciousness. From cosmology to various ritual practices and genres of oral traditions such as proverbs, poetry and short stories are all brought to bear on the reality of death. Not a day goes by that speakers of the Yoruba language do not make mention of death as both a phenomenon and a certainty.

Among the Owo Yoruba people, Iku (death) is likened to the hippopotamus (eyinmi/erinmi), whose heavy weight no person can carry and whose presence one cannot run or escape from. This conveys the dilemma of a bereaved child who can neither carry the body of a deceased parent nor is courageous enough to abandon it, highlighting the helplessness of one when confronted by death.

In Yoruba folk tales, death is also portrayed as an old haggard man who carries a heavy club with which he kills his victims. No one is spared. The young, the old, kings, chiefs, commoners and the rich can all be his victims. It is assumed that at creation, and before individuals leave Orun (the otherworld), the preconscious mind is made aware of when death will strike in Aiye (this world), and when they will return to Orun. The appointed date, however, is never known.

Yancy: According to Yoruba, should human beings embrace death? And if so, how or why?

Olupona: It is assumed that death doesn’t end a person’s life, but instead marks a passage from one realm of existence to the next. Hence, the Yoruba believe there is an afterlife (or an “afterdeath”) in which the living dead exist as part of the sacred cosmos.

There is also an ambiguous response to death, depending on the circumstances surrounding the event. Death in very old age, for example, is welcomed as a fulfillment of one of the cardinal life quests. This form of death is celebrated by the community as a necessary transition to the ancestral world. On the other hand, deaths that occur in infancy, childhood or young adulthood are frowned upon and not often celebrated, because the deceased was yet to accomplish his or her mission on earth.

Deaths involving unnatural causes fall into the same category. It is by tradition a taboo for older people to participate in young people’s funerals, to ward off the malicious knell of death. This is also because the death of a younger person is considered “bad death,” not worth celebrating by the elderly. It is a taboo for kings (Oba) to witness funeral celebrations or behold a dead body.

Yancy: Is there an account within Yoruba that explains why we fear death?

Olupona: Absolutely. Yoruba personal names reveal a lot about why they fear death. Consider the following: Ikubamije, “Death has ruined me”; Ikubileje, “Death has wreaked havoc on our family”; Ikugbeye, “Death has taken away our dignity”; Ikumone, “Death is no respecter of persons”; Ikumofin, “Death does not recognize any law”; Ikupakin, “Death has killed the hero”; Ikupelero, “Death has killed a socialite”; Ikusika, “Death has committed acts of wickedness,” and so on.

The dead must also be called upon to avenge his or her own wrongful death. My maternal grandmother once told me a story of a great-uncle who was murdered on my grandfather’s farm while he was working and whose body was brought home for burial rites. My grandfather, being a devout Christian, was opposed to the rituals of “oku riro,” preferring to leave everything to God. Somehow, before the seventh day of the burial, the deceased avenged his own death by pursuing the murderer in his sleep. The murderer was said to have suddenly woken up from his sleep screaming as the deceased spirit “chased” him. Not long after, the murderer was reported to have collapsed and died!

Yancy: Are there specific circumstances under which we should fear death, according to Yoruba?

Olupona: Yes, especially when deaths are unusually frequent or inexplicable. The Yoruba are accustomed to finding causes of death and ensuring their non-recurrence. For example, they fear death of children known as “abiku” who are associated with “spirit children.”

These are children who are reincarnated to be reborn and die no matter what. These children are stuck in a perpetual cycle that prevents them from growing into adulthood. Death of spirit children defies the Yoruba mind so much so that abiku are said to confound even the most knowledgeable medicine men and women.

They also fear death that occurs in mysterious circumstances such as when a couple dies the day after their wedding, a very experienced swimmer drowns and dies, a ruler dies shortly after ascending the throne, a perfectly healthy individual dies suddenly without any apparent signs of sickness, or all of one’s children or siblings dying on the same day, even though they are all located in different places. All of these examples make one reflect on the significance of Yoruba personal names like Ikudefu, “Death has become a wind”; Ikuosunwon, “Death is not nice”; and Ikujaiyesimi, “O Death, let the community have a breathing space” and Ikudabo, “O Death, please stop.”

Yancy: Is there a relationship between how we live our lives here on earth and what happens after we die?

Olupona: In traditional Yoruba cosmology, there seems to be no explicit reference to final judgment as in Islam and Christianity; humans are enjoined to do well in life so that when death eventually comes, one can be remembered for one’s good deeds. One’s character may be measured in terms of virtue and vice, or in deeds that are worthy of reward. For the Yoruba, this is the core essence of religion.

For example, a prosperous and successful individual can be said to be reaping the good deeds of his/her deceased parents during their lifetime. Likewise, an individual who suffers may be said to be reaping the bad deeds of his or her deceased parents. So, it is assumed that the descendants of a wicked individual may live to reap the punishment meant for his/her parents. Yoruba religion shares this idea with Christianity as in the account of a worthy man of note in the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes, Chapter 44.

Yancy: How do the Yoruba let go and grieve those who have died?

Olupona: The Yoruba spend an awful lot of time and energy on burying their dead. It is assumed that a “proper” burial is required, not only to ensure the deceased’s peaceful transition to the world of the ancestors, but to ensure that those of the living are not affected by death’s visit. Burial ceremonies and rituals may take up to an entire week and involve the deceased extended and immediate family, their lineage and clan, residents of their town and ultimately the whole community.

In certain places, it is also assumed that the dead must be encouraged to depart quickly and visit the open market (Oja) where they may make appearances as spirits. Among the Owo Yoruba people, it is believed that the dead, through a journey back home, must first return to the sacred city of Yoruba creation, Ilé-Ifè, on their way to the ancestral realm.

In the Owo Yoruba tradition, where age groups are well established, burial rituals and ceremonies are taken seriously. The members of these age groups are responsible for digging the graves of their peers or their peer’s parents who have passed on to ensure that they are properly buried. Hence, the Yoruba would say, “Eni gbele lo sinku, eni sunkun ariwo lo pa.” Literally — “It is the gravediggers who are the real mourners; relations who shed tears are merely making loud noises.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!