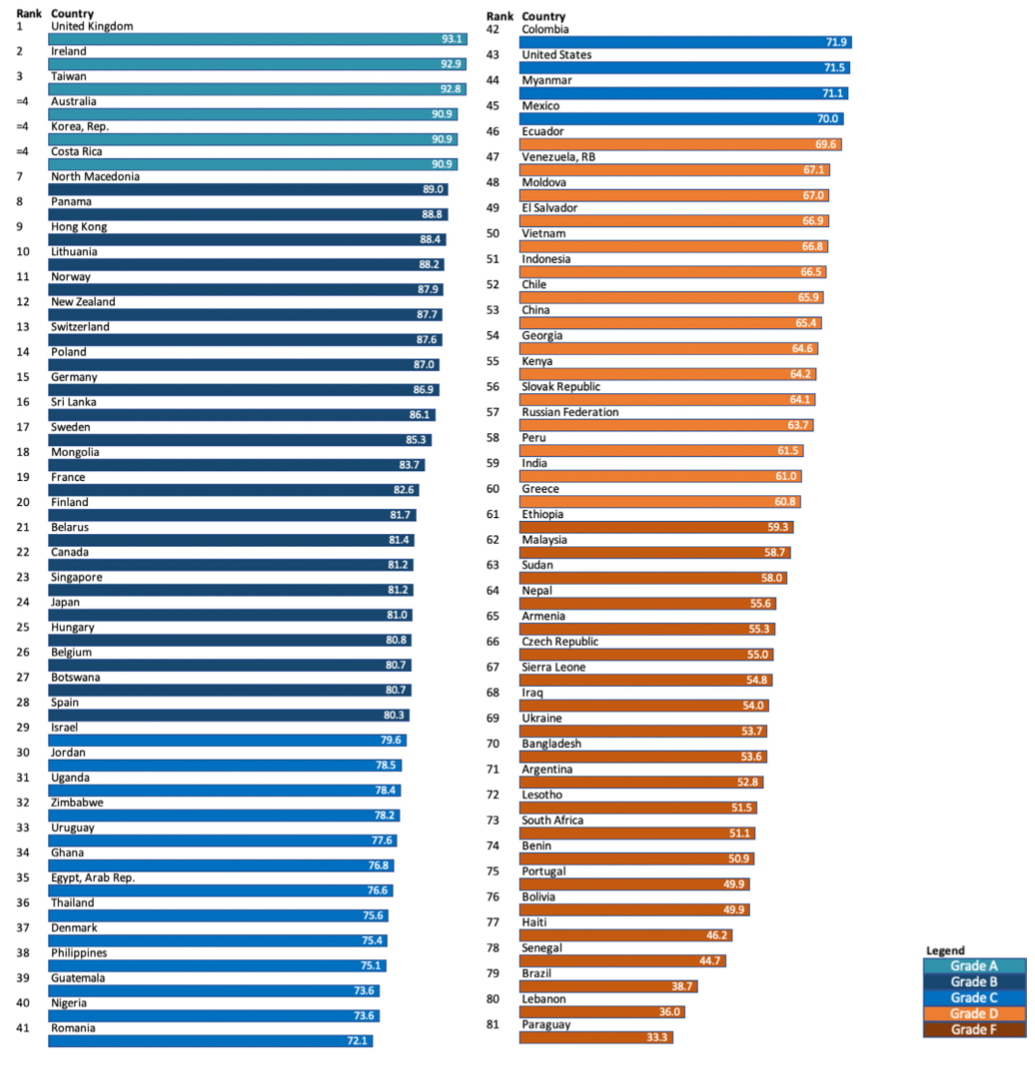

Health and social systems around the world are failing to give appropriate, compassionate care to people who are dying and their families. According to a new Lancet Commission, today’s current overemphasis on aggressive treatments to prolong life, vast global inequities in palliative care access, and high end-of-life medical costs have lead millions of people to suffer unnecessarily at the end of life.

The Commission calls for public attitudes to death and dying to be rebalanced, away from a narrow, medicalised approach towards a compassionate community model, where communities and families work with health and social care services to care for people dying.

Bringing together experts in health and social care, social science, economics, philosophy, political science, theology, community work, as well as patient and community activists, the Commission has analysed how societies around the world perceive death and care for people dying, providing recommendations to policy makers, governments, civil society, and health and social care systems.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has seen many people die the ultimate medicalised death, often alone but for masked staff in hospitals and intensive care units, unable to communicate with their families, except digitally”, says Dr. Libby Sallnow, palliative medicine consultant and honorary senior clinical lecturer at St Christopher’s Hospice and UCL (UK) and co-Chair of the Commission, “How people die has changed dramatically over the past 60 years, from a family event with occasional medical support, to a medical event with limited family support. A fundamental rethink is needed in how we care for the dying, our expectations around death, and the changes required in society to rebalance our relationship with death.”

The Commission focuses primarily on the time from when a person is diagnosed with a life-limiting illness or injury, to their death and the bereavement affecting the lives of those left behind—it does not cover sudden or violent deaths, deaths of children, or deaths due to injustice.

Death and dying have become over-medicalised, hidden away and feared

Over the past 60 years, dying has moved from the family and community setting to become primarily the concern of health systems. In the UK for example, only one in five people who require end of life care are at home, while about half are in hospital (table 2).

Global life expectancy has risen steadily from 66.8 years in 2000 to 73.4 years in 2019. But, as people are living longer, they are living more of these additional years in poor health, with years lived with disability increasing from 8.6 years in 2000 to 10 years in 2019.

Prior to the 1950s, deaths were predominantly a result of acute disease or injury, with low involvement from doctors or technology. Today, the majority of deaths are from chronic disease, with a high level of involvement from doctors and technology. The idea that death can be defeated is further fuelled by advances in science and technology, which has also accelerated the over-reliance on medical interventions at the end of life.

And, as healthcare has moved centre stage, families and communities have been increasingly alienated. The language, knowledge, and confidence to support and manage dying have been slowly lost, further fuelling a dependence on health systems. Despite this, rather than being viewed as a professional responsibility for the doctor, and a right for all people and families who wish it, conversations about death and dying can be difficult and uncomfortable and too often happen in times of crisis. Often they don’t happen at all.

“We will all die. Death is not only or, even, always a medical event. Death is always a social, physical, psychological and spiritual event and when we understand it as such we more rightly value each participant in the drama,” adds Commission co-author, Mpho Tutu van Furth, priest, Amstelveen, Netherlands.

Worldwide, too many people are dying a bad death

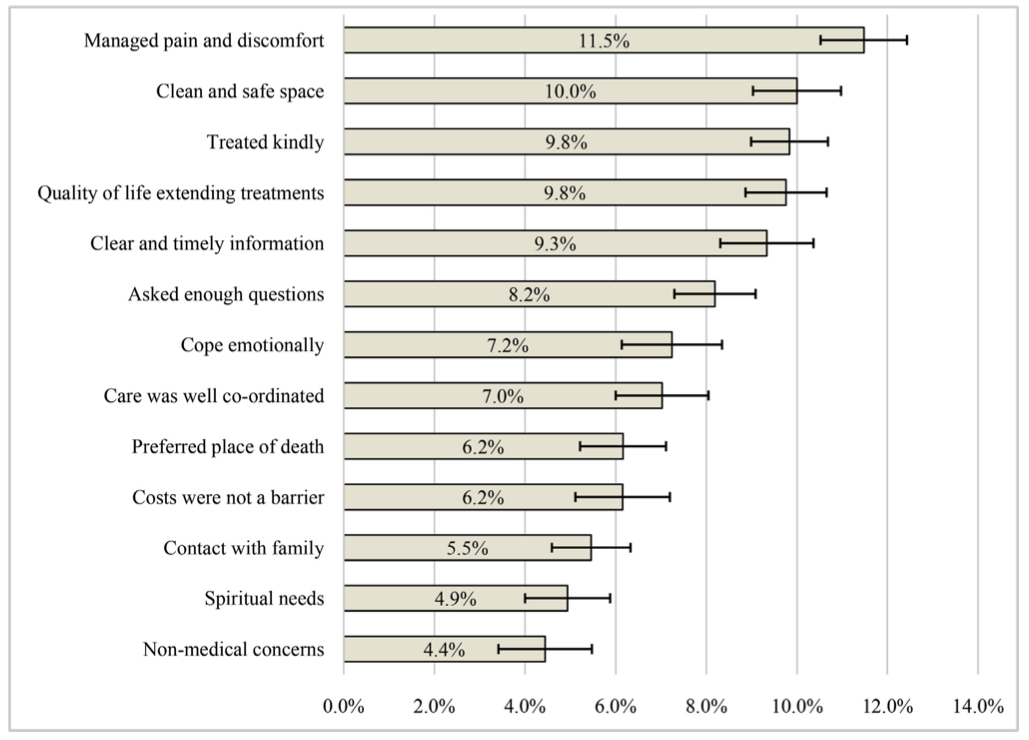

While palliative care has gained attention as a specialty, over half of all deaths happen without palliative care or pain relief, and health and social inequalities persist in death.

Interventions often continue to the last days with minimal attention to suffering. Medical culture, fear of litigation, and financial incentives also contribute to overtreatment at the end of life, further fuelling institutional deaths and the sense that professionals must manage death.

Untreated suffering, vast inequalities, and aggressive medical treatments have come at a high cost. A disproportionate share of the total annual expenditure in high income countries goes towards treatment for those who die, suggesting that treatments at the end of life are being provided at a much higher threshold than for other treatments.

In high income countries, between 8% and 11.2% of annual health expenditure for the entire population is on the less than 1% who die that year (table 6). Care in the last month of life is costly and, in countries without universal health coverage, can be a cause of families falling into poverty.

“Dying is part of life, but has become invisible, and anxiety about death and dying appears to have increased. Our current systems have increased both undertreatment and overtreatment at the end of life, reduced dignity, increased suffering and enabled a poor use of resources. Healthcare services have become the custodians of death, and a fundamental rebalance in society is needed to re-imagine our relationship with death,” says Dr. Richard Smith, co-Chair of the Commission.

A fundamental change to society’s care for the dying is needed

The Commission sets out five principles of a new vision for death and dying:

1. The social determinants of death, dying and grieving must be tackled, to enable people to lead healthier lives and die more equitable deaths.

2. Dying must be understood to be a relational and spiritual process rather than simply a physiological event, meaning that relationships based on connection and compassion are prioritised and made central to the care and support of people dying or grieving.

3. Networks of care for people dying, caring, and grieving must include families, wider community members alongside professionals.

4. Conversations and stories about everyday death, dying, and grief must be encouraged to facilitate wider public conversations, debate, and actions.

5. Death must be recognised as having value. “Without death, every birth would be a tragedy.”

The Commission recognises that small changes are underway—from models of community action to discuss death, national policy changes to support bereavement, or hospitals working in partnership with families. While wholescale change will take time, the Commission points to the example of Kerala, India, where over the past three decades, death and dying have been reclaimed as a social concern and responsibility through a broad social movement comprised of tens of thousands of volunteers complemented by changes to political, legal, and health systems.

“Caring for the dying really involves infusing meaning into the time left. It is a time for achieving physical comfort; for coming to acceptance and making peace with oneself; for many hugs; for repairing broken bridges of relationships and for building new ones. It is a time for giving love and receiving love, with dignity. Respectful palliative care facilitates this. But it can be achieved only with broad-based community awareness and action to change the status quo,” says co-author Dr. M.R. Rajagopal, Pallium India, India.

To achieve the widespread changes needed, the Commission sets out key recommendations for policy makers, health and social care systems, civil society, and communities, which include:

- Education on death, dying, and end of life care should be essential for people at the end of life, their families and health and social care professionals.

- Increasing access to pain relief at the end of life must be a global priority, and the management of suffering should sit alongside the extension of life as a research and health care priority.

- Conversations and stories about everyday death, dying, and grief must be encouraged.

- Networks of care must lead support for people dying, caring, and grieving.

- Patients and their families should be provided with clear information about the uncertainties as well as the potential benefits, risks, and harms of interventions in potentially life-limiting illness to enable more informed decisions.

- Governments should create and promote policies to support informal carers and paid compassionate or bereavement leave in all countries.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!