The Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death, subtitled ‘Rebalancing and Revaluing Death and Dying: Bringing Death Back Into Life’, is a timely, cogent and illuminating foray into an aspect of life that few seem to consider, despite it being the one thing that we have in common – we, and everyone we know, will all die someday.

The Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death, due for imminent release, is part of a series of publications featuring the collaborative work of a broad and diverse range of academic partners, writers, activists, and others, who investigate the world’s most urgent scientific, medical and global health concerns. Their aim is to assess a prevailing issue and provide recommendations that could change health policy or improve practice.

This particular report, subtitled “Rebalancing and Revaluing Death and Dying: Bringing Death Back Into Life”, is a timely, cogent and illuminating foray into an aspect of life that few seem to consider, despite it being the one thing that we have in common – we, and everyone we know, will all die someday.

The Report on the Value of Death is arresting for several reasons, which benefit from a nuanced understanding of what professor emeritus at Arizona State University and author Robert Kastenbaum has termed “death systems”. These are “the means by which death and dying are understood, regulated and managed”, which Kastenbaum first described as “interpersonal, socio-physical and symbolic networks through which an individual’s relationship to mortality is mediated by society.”

These systems are complex, multidimensional and mutable, not easily changed, and shaped by spectrum of cultural, religious, spiritual, political and legislative practices, which “implicitly or explicitly determine where people die, how dying people and their families should behave, how bodies are disposed of, how people mourn, and what death means for that culture or community.” (The report limits itself to death and dying, and does not examine what happens to the dead.)

“Society and the medical world have considered black lives cheap.”

Death systems, the authors point out, are “not benign”. An afterword by Mpho Tutu van Furth, a South African Anglican priest, author and activist who has lived in the US, provides a corrective to the predominantly white, wealthy and Western perspective that embeds itself in much of the report’s narrative, which the commission is self-consciously aware of.

Writing from her own perspective and not “on behalf of two-thirds of the world’s population” who do not enjoy access to healthcare, she attests to her own experience as a black South African woman and mother to two African American children, picking apart the cultural anomalies she witnessed growing up and going some distance further.

“I saw the white flight from ageing and death,” she writes. “Black people had no illusion we could escape death. Black South Africans did not desire immortality. In death we would be gathered with our ancestors. ‘Going home’ to our forebears was considered the reward for a life well lived.”

This, however, takes place in the context of malevolent racism, both in South Africa and the US. “Society and the medical world,” she writes, “have considered black lives cheap.” She squarely accuses racism as a determinant of death’s value, saying that to “ascribe the correct value to death we must assign the right price to every life”, and provides the example of how Covid has disproportionately affected and afflicted black people everywhere.

Initiated before the current pandemic, the report nevertheless situates itself here, yet looks to the future.

Interestingly, it presents evidence that our collective experience of death during Covid has “further fuelled the fear of death”, instead of the opposite. Daily death tallies and statistics have not normalised death or brought it closer, but spurred further abstraction. Supporting this claim, the report draws attention to the extreme “medicalised death” (for some) that Covid has provided: death that has occurred in the forbidden province of a sealed hospital, staffed by masked and muffled and often stressed personnel, with limited communication between family members. We’ve had more death, but moved it even further away.

The authors note: “The increased number of deaths in hospital means that ever fewer people have witnessed or managed a death at home. This lack of experience and confidence causes a positive feedback loop which reinforces a dependence on institutional care of the dying.

“Medical culture, fear of litigation, and financial incentives contribute to overtreatment at the end of life, further fuelling institutional deaths and the sense that professionals must manage death. Social customs influence the conversations in clinics and in intensive care units, often maintaining the tradition of not discussing death openly. More undiscussed deaths in institutions behind closed doors further reduce social familiarity with and understanding of death and dying.”

“Death is essential… Without it, every birth would be a tragedy… and civilisation would be unsustainable.”

This experience, reinforcing the pervasive idea of healthcare services as the legitimate and proper “custodian of death”, is a trend initiated generations ago for a bevy of reasons. The authors relay that over the past 70 years, the “shifting role of family, community, professionals, institutions, the state, and religion has meant that healthcare is now the main context in which many encounter death”.

A natural death, in this paradigm, is simply considered as the cessation of medical support, and, according to the social critic Ivan Illich, “dying has become the ultimate form of consumer resistance”. (Similarly, the co-founder of the Death Café movement, the late Jon Underwood, found a strong parallel between death denial and consumer capitalism. We buy stuff to perpetuate the idea of immortality through ownership, to feel alive, imagining that possessions confer meaning to life. Yet even if they last, we don’t.)

The responsibility of healthcare, commonly understood as the prolonging of life and avoidance of death, therefore regards death itself as a failure. At the heart of the report is an urgent and radical proposal – that we unpick and redetermine what medicine should do, and revalue death, recognising that it is not only normal and natural, but valuable, and has much to teach and bestow on us. After all, we were designed to die. We are a part of nature, as the pandemic has reminded us. “Death is essential,” the authors write. Without it, “every birth would be a tragedy” and “civilisation would be unsustainable”.

In rediscovering the intrinsic value of death, lost in the attrition of community skills and experience in care for our dying, and the concurrent emergence of life-saving medical technologies and the outsourcing of death, we are now urged to bring death closer, to talk about it and recognise that it provides an opportunity to build and maintain the relationships that sustain life itself.

In losing death, we lose life.sp;

That death has become rarefied, obscured, mystified and hidden is a core problem, entrenching an imbalance that the recommendations of the report attempt to address in practical terms. The commission (which is how the authors refer to themselves, continually incorporating new members and ideas and inviting participation at every turn) is essentially concerned with the different ways we die, and proposes that death, dying and grief provide an acute lens not just into different death systems but into structural inequality and power dynamics which need urgent attention and change.

For example, women are disproportionately affected by death, and are typically seen as caregivers for the afflicted and dying, spending at least 2.5 times more time than men in unpaid care and domestic work. (In my own group of death doulas and end-of-life carers, for example, I am the only person who identifies as a man in a group of 40 women.)

In addition, widows are routinely stigmatised, in both rich and poor contexts, and commonly denied access to property or assets after the death of a spouse, whose existence often defines their own, and sometimes forced into degrading post-marriage rituals (treated as common family property) or shunned from employment or society. In middle- and high-income environments too, widowhood presents difficult social barriers and loss of status, income and life chances.

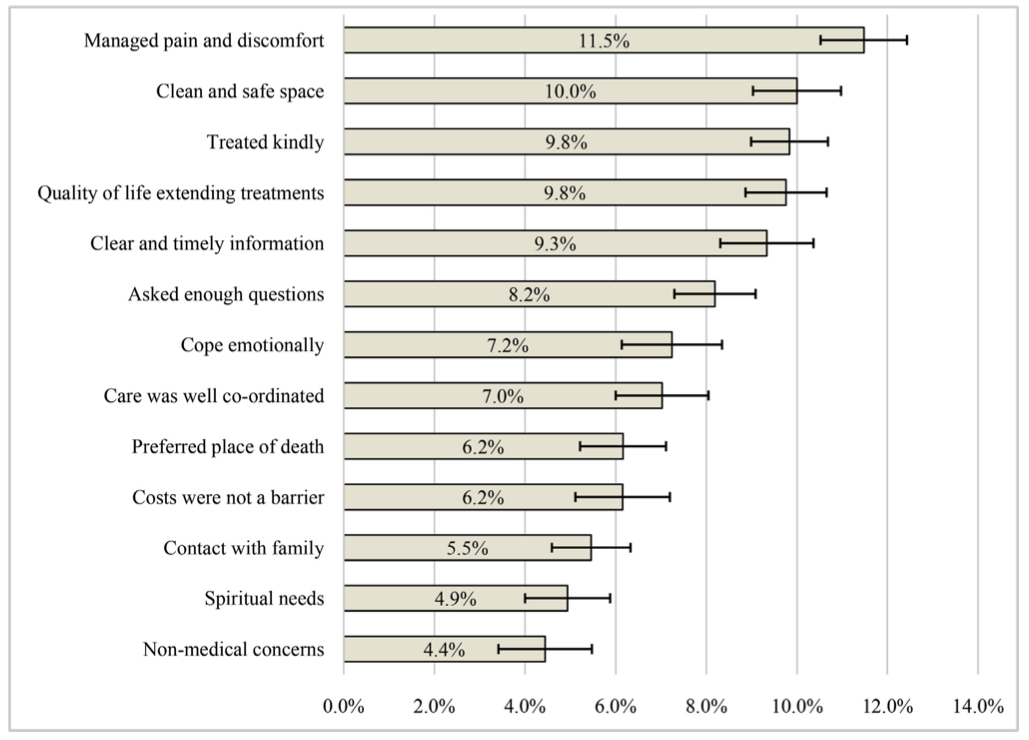

We are continually reminded in many examples in this report that the “impact of race, class, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, or other forms of discrimination on mortality rates, access to care, or the incidence of diseases or conditions, is well established”. Indeed, inequality is emphatically expressed in the perverse finding that those who receive the most care often don’t need it, while those who need it the most don’t get it. Poor people usually experience poor death. The relatively well-off may attempt some form of inoculation via medical care, but this too tends to have an often poor result. Death could clearly be better for everyone. The authors contend that “most conditions for a good death could be offered to most dying people, without costly medical infrastructure or specialised knowledge”.

At the heart of this paradoxical imbalance, the report locates the prevalence of “overtreatment” at the end of life as a particularly pernicious and often damaging practice and one which consumes a massive proportion of healthcare budgets the world over.

A startling finding is that in the last month of a person’s life, whether in a resource-rich or poor context, a stupendous spike in costs usually occurs, frequently bankrupting surviving family – despite having no positive benefit to the dying, and often increasing suffering.

But perhaps this is old news for people who’ve found themselves in this situation, unable to delimit potentially life-extending treatment, which doesn’t necessarily improve the quality of life at all, for fear of being held accountable for death, or hastening it, and going against the grain of the medical impetus to prolong. In my own experience, I recall the glee conveyed by a daughter and her terminally ill mother who had together decided to abandon the crippling costs of another round of pointless chemotherapy and go on a final road trip together instead.

Medicine’s remit to extend life isn’t appropriate where there is no realistic prospect of influencing life’s quality. While the palliative care movement is fortunately making strong if uneven advances for limiting pain at the end of life, and building models of holistic, integrated and team-based care that includes families to provide support that focuses on improving life’s quality in balance with death’s inevitability, far too many people die of common conditions that could be treated, and with no pain relief.

The World Health Organization reports that only 14% of people needing palliative care receive it. (This is the focus of a separate Lancet Commission report but is frequently referred to here.)

The report, drawing from a deep well of research (all of which is available on the commission’s website) presents fascinating evidence of the frequency of hope and bias as causes of overtreatment, further entrenching the medicalisation of death. Hope, they posit, can encourage confirmation bias, where the subconscious selection of information usually accords with a desired outcome – to stay alive. This racket is often run in collusion with afflicted individuals, their worried families and healthcare professionals alike. Bias similarly expresses itself in treatments recommended with little chance of success, even at any cost.

For example, in a study of 1,193 patients with late-stage cancer, 60% and 80% respectively of those with lung cancer and colorectal cancer receiving palliative chemotherapy “expected the treatment to cure their illness despite the treatment not intended to be curative”. Doctors, meanwhile, routinely show bias in their assessment of the likelihood of curative treatment. Better conversations need to happen, that recognise and are free of fear.

Perhaps this is unsurprising in a system where relationships and networks are replaced with professionals and protocols. In Cape Town, I recently listened to an esteemed city official describe ways to “optimise death chain management” during the pandemic. Psycho-spiritual support and home-based community care were off the radar.

Of several discrete yet overlapping sections in the report, the chapter on “advanced life directives” is particularly convincing as evidence that a positive shift in our death systems can be achieved through a reorganisation of relationships, without much expense.

Considering the level of end-of-life you deem appropriate (such as no insertion of artificial feeding tubes) can form part of a healthy communication between family members, and provide a binding template for your instructions when you may no longer be able to convey them, especially to medical staff. This, the authors suggest, should not be regarded as a “difficult” conversation, but recast as an “essential one”. (Readers might find some assistance here)

It seems like we have lost the ability to talk about death, as though talking about it is morbid, even fatal… We can perhaps embrace the idea that talking about death is good for life.

The report suggests that this conversation is seen as a process rather than an event, and draws from Atul Gawande’s seminal book, Being Mortal, to help frame this. In the context of illness, he asks: What is your understanding of where you are and of your illness? What are your fears or worries for the future? What are your goals and priorities? What outcomes are acceptable to you? What are you willing to sacrifice and not? And later, what would a good day look like?

The consequences of not having these conversations are severe. Having them, on the other hand, can limit suffering and provide pathways to healthy grief and loss that is less complicated than it might be. It seems like we have lost the ability to talk about death, as though talking about it is morbid, even fatal.

The death doula movement, the palliative care movement and other cultural projects promoting awareness of death, such as Death Cafés and the “death positive movement”, are changing this. These have, argues the sociologist Lyn Lofland, even heralded the age of “thanatological chic”. Perhaps this is necessary. For a rebalancing and revaluing of death, the report suggests, entails the active promotion of “death literacy”, which is something we can all learn. Evidence suggests, the report says, “that talking collectively about these issues can lead to an improvement in people’s attitudes and capabilities for dealing with death”. We can perhaps embrace the idea that talking about death is good for life.

This requires more change. The report mentions that until relatively recently, just two generations ago, most children would have witnessed a dead body. Now however, it is deemed some kind of aberration to have seen a corpse, as something remarkable and untoward, even unnatural. Many people in mid-life have never laid their eyes on the lifeless remains of a former co-traveller. We have become alienated from death, treating it as something to be avoided. Indeed, a plethora of scientific, technological, social and even religious endeavours reveal, in their quest for immortality, a possible anxiety that life is somehow insufficient and lacking. This impulse to escape mortal confines raises some profound philosophical, ethical and practical questions, not least of which is a question about access and further inequality. (Mpho Tutu van Furth’s earlier testimony regarding the welcoming return home in death for black Africans is a useful counterpoint, once again.)

Several of these initiatives are briefly described in the report, encompassing a quest to preserve life through anti-ageing techniques and a confabulation of associated technologies, the lasting idea of a magical elixir, uploading a digital mind and memories to the cloud, cryogenics, cloning, the egoistic impulse to create “legacy”, even the belief in an immortal soul forms part of this complex – which, bluntly, is an aversion to physiological death and pulling away from the thing that is most essential to life – our death. The Scottish-born former director of the Institute for the Future, Ian Morrison, is quoted here, joking that “Scots see death as imminent. Canadians see death as inevitable. And Californians see death as optional.”

Assisted dying, which is legal in Canada, receives broad examination in the report. As it seems likely to become more widespread, according to the authors, and is the subject of increasing debate worldwide, including South Africa, the report provides a refreshing summary of questions about assisted dying that demand further inquiry. These are proposed without the delimiting taint of an imposed morality, which often confounds consideration of this very germane topic.

A similarly dispassionate yet inspired gaze is deployed into consideration of five possible future scenarios for death and dying, as well as an extensive description of the remarkable paradigm shift in Kerala, India (population 35 million) where “dying from a life-limiting disease is a social problem with medical aspects rather than the commonly held converse view”.

The report concludes with a list of recommendations organised into various categories and the enumeration of the qualities required for what the authors describe as a “realistic utopia”, a desired model inspired by the Keralan example, and a way that each of us can work to change the death systems we inhabit.

Briefly, these qualities are: that “the social determinants of death, dying, and grieving are tackled”; that “dying is understood to be a relational and spiritual process rather than simply a physiological event”; that “networks of care lead support for people dying, caring, and grieving”; that “conversations and stories about everyday death, dying, and grief become common”; and perhaps most importantly, that “death is recognised as having value”.

Incredibly, even though death and dying are part of life – an everyday part of life affecting us all, as we are continually exposed to the death of others and live with the certainty of our own mortality, indeed, are embroiled in the twin process of living and dying in every moment as we move from birth – death is not only absent from many medical conversations, but social ones too.

This report encourages the fact that we clearly have much to talk about. Death is part of life, not something that happens at the end of it. Breaking the taboo about speaking about death feels transgressive and can be revelatory.

Revaluing death, as this remarkable report suggests, has the profound ability to make lives better. The philosopher Martin Heidegger, who examined our relationship with death and who is quoted in the report, reminds us that although we may apprehend the death of others, no one else can “die my death for me”. Acknowledgment and contemplation of this ineluctable fact free us to “authentically become who we are” and, hopefully, encourage us to take up the shared responsibility of affording the same value to the death, and life, of everyone who draws breath.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!