by Sarah Kliff

In my family, we don’t really talk about death. But, every now and then, we joke about it.

For some reason, there is a running joke among my immediate family about how my parents will die. Specifically, my brother and I will come home for Thanksgiving one year and find them decomposing on the couch.

Yes, this is a bizarre thing to crack jokes about. But it’s also, in its own, ghoulish way, a bit of a fantasy — an affront to the way that Americans tend to die in the 21st century, with ticking machines and tubes and round-the-clock care. In this joke, my parents’ death is a simple, quiet, and uncomplicated death at home.

I joke about death because I am as terrified of having serious end-of-life conversations as the next person. Usually I don’t have to think much about dying: my job as a health-care reporter means writing about the massive part of our country devoted to saving lives — how the hospitals, doctors, and drugs that consume 18 percent of our economy all work together, every day, to patch up millions of bodies.

But recently, the most interesting stories in health care have been about death: the situations where all the hospitals, doctors, and drugs in the world cannot halt the inevitable.

In September, Ezekiel Emanuel — an oncologist, bioethicist, and health-policy expert — wrote a powerful essay for The Atlantic about why he will no longer seek medical treatment after he’s 75. “Living too long is also a loss. It renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived,” he wrote. At 75, Emanuel says, he will become a conscientious objector to the health-care system’s life-extending work. “I will need a good reason to even visit the doctor and take any medical test or treatment, no matter how routine and painless. And that good reason is not ‘It will prolong your life.’ I will stop getting any regular preventive tests, screenings, or interventions. I will accept only palliative — not curative — treatments if I am suffering pain or other disability.”

The following month, Atul Gawande, a surgeon, published his new book, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters In the End. He argues that his profession has done wonders for the living, but is failing the dying. “Scientific advances have turned the processes of aging and dying into medical experiences,” he writes. “And we in the medical world have proved alarmingly unprepared for it.”

After months of watching this debate unfold, I’ve realized something that feels, to me at least, like a revelation. This conversation isn’t about death at all. “Death” is the word that confuses the conversation, that makes people too afraid, and too angry, and too frantic to keep talking. This conversation is really about autonomy. It is about what makes life worth living, and if, in keeping people alive for so long, we are consigning them to a fate worse than death.

When death came quick and fast, there was no fight to remain autonomous. Two graphs near the beginning of Gawande’s book help make clear how recently this tension developed. There is this first graph, which shows what life used to be like a century ago: moving along, steadily, until some horrific event happened. Maybe it was a disease, maybe it was a car accident (or, even earlier, a horse and buggy accident). Whatever the event, death happened quickly.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919162/gawande_chart_1.0.png) (Metropolitan Books)

(Metropolitan Books)

Modern medicine has done incredible things. A woman born in the United States in 1885 had an average life expectancy of just over 44 years. I was born in 1985 and, thanks to advances in technology and sanitation, my life expectancy is 82. But these improvements have also changed, and extended, how we die. “The curve of life becomes a long, slow fade,” Gawande writes.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919212/gawande_chart_2.0.png) (Metropolitan Books)

(Metropolitan Books)

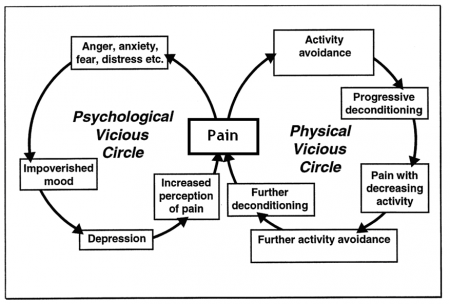

That slow, long fade means we get to live longer, but often at the cost of our autonomy, and, in the view of some, at the cost of our most essential self. Autonomy — the freedom to see the people we want, partake in the activities we enjoy, and wake up each morning to our own agenda — is a value that arguably all of us hold dear. Even as physical independence disappears, it is possible (albeit more challenging) for autonomy to remain and for the elderly to retain control of how they spend their days.

But aging makes the facilities, both mental and physical, that we need to maintain our autonomy, weaker. The activities we enjoy and the ones we find core to our identity become more difficult to pursue.

As we get older, we lose the mastery we once had over the world around us, the admiration we once inspired in those we loved. Simple tasks — driving to a family member’s home, grocery shopping, preparing meals — become harder. The things we want to do aren’t always things we can still decide to do. Emanuel writes about the plight of his father, who had a heart attack followed with a bypass surgery at age 77. It was more difficult to do the things that defined his existence:

Once the prototype of a hyperactive Emanuel, suddenly his walking, his talking, his humor got slower. Today he can swim, read the newspaper, needle his kids on the phone, and still live with my mother in their own house. But everything seems sluggish. Although he didn’t die from the heart attack, no one would say he is living a vibrant life.

Emanuel doesn’t see this as unique to his father. He thinks this is the norm — that we have fooled ourselves into believing we have prolonged life, when instead we have prolonged the process of death. He writes that half of people 80 and older have functional limitations, and a third of people 85 and older have Alzheimer’s. And as for the remainder, they, too, slow and stumble, in mind as well as body.

“Even if we aren’t demented, our mental functioning deteriorates as we grow older,” he says. “Age-associated declines in mental-processing speed, working and long-term memory, and problem-solving are well established. Conversely, distractibility increases. We cannot focus and stay with a project as well as we could when we were young. As we move slower with age, we also think slower.” We become necessarily capable of making the decisions that we used to. Our bodies and brains simply won’t allow it. This isn’t to say autonomy disappears, but that it takes more support and conscious effort to plan.

Emanuel’s argument is fundamentally pessimistic about the future that we all face: it suggests that, even as we learn more about extending life, we won’t be able to improve the quality of life that precedes death.

Gawande’s book acknowledges that the body will break down, too. The second chapter, “Things Fall Apart,” is devoted to the ways that our body — from the color in our hair to the joints of our thumbs — diminishes at the end of life.

There are sections from this chapter that haunt my nights. The brain shrinks an astonishing amount in the course of a normal lifetime, with the frontal sections that control memory and planning diminishing the fastest. “At the age of 30, the brain is a three-pound organ that barely fits inside the skull,” Gawande writes. “By our seventies, gray-matter loss leaves almost an inch of spare room.” This explains, by the way, why falls can be so damaging for the elderly: their brain has a spare inch of space to get jostled around.

“Living too long is also a loss,” he writes. “It renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived.”

Most of us look at nursing homes — with their scheduled meals, constant supervision, adult diapers, wheelchair-bound residents, and depressing bingo nights and we think: I do not want that. I do not want to give up control over my own life, my ability to see the people I want to see and do the things I want to do. I do not want to live a life where I can’t dress myself, where I’m not allowed to feed myself, where I’m barred from living any semblance of the life that I live right now.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919148/vox-share__43_.0.png)

As Gawande points out, assisted living and nursing facilities sometimes rob residents of the autonomy they’d have elsewhere. A patient who is bedridden, for example, likely ends up eating on a schedule to fit into the nurse’s rounds — not whenever they feel like having a snack. Getting dressed can be handed over to staff because they can do it more efficiently.

“Unless supporting people’s capabilities is made a priority, the staff ends up dressing people like they’re rag dolls,” he writes. “Gradually, that’s how everything begins to go. The tasks come to matter more than the people.”

But somehow, millions of Americans end up with life: there are 1.5 million nursing-home residents in America right now. On average, those nursing-home residents live in these facilities for two years, three months, and 15 days.

Here, however, Gawande identifies an unexpected culprit: the young, not the old.

At one point in the book, Gawande speaks with Keren Wilson, the woman who opened the country’s first assisted-living facility. And she gave him one of those quotes that every reporter dreams of — a single sentence where, after hearing it, you can’t ever look at the issue in the same way again. “We want autonomy for ourselves and safety for those we love,” she says.

One reason that nursing homes are so soulless is that it’s often not the residents who made the decision about where they would live. Instead, it’s their caretakers — often adult children — who chose the home, and their end-of-life priorities are frequently different from their parents’. Namely, where their parents value autonomy, children value safety. Wilson continues:

Many of the things that we want for those we care about are the things that we would adamantly oppose for ourselves because they would infringe upon our sense of self.

It’s the rare child who is able to think, “Is this place what Mom would want or like or need?” It’s more like they’re seeing it through their own lens. The child asks, “Is this a place I would be comfortable leaving Mom?”

Gawande argues that what’s wrong with how we die now is that the patient — the person facing the end of life — is not the decision-maker. The locus of power shifted away from the people who will actually experience living in a nursing home and into the hands of their full-grown children, who often pay much of the bill.

Gawande and Wilson don’t argue that children are acting maliciously, trying to thwart the life that their parents wish to lead. It’s just that grown children and their elderly parents often have conflicting views of what matters at the end of life. Children often want every precaution taken to prevent injuries and falls. The elderly often want to live as autonomous a life as they can, even if it entails more risk. There’s one 89-year-old woman Gawande talks to who makes this point especially clearly, echoing what the dozens of other elderly interviewees told him:

“I want to be helpful, play a role,” she said. She used to make her own jewelry, volunteer at the library. Now, her main activities were bingo, DVD movies, and other forms of passive group entertainment. The things she missed most, she told me, were her friendships, privacy, and a purpose to her days … it seems we’ve succumbed to a belief that, once you lose your physical independence, a life of worth and freedom is simply not possible.

One of the more depressing anecdotes in Gawande’s book details how food has become a battleground in nursing homes; the “Hundred Years War,” as he describes it. The battles — with a diabetic who hoards cookies, the Alzheimer patient who wants to eat at non-standard meal times — exemplify the tensions between safety and autonomy that pervade the modern nursing-home experience.

“We make these choices all the time in our home and taking those away from people takes away really fundamental things about who they are, what makes a life worth living,” Gawandetold me in an interview. “The biggest complaints about patients in nursing homes — by the way you can get a report filed against you in a nursing home — are about violating food rules. So you’ll see Alzheimer’s patients hoarding cookies. Give them the damn cookie. They might choke on it, but what are we trying to keep them alive for? Let’s allow some risk, even in the Alzheimer’s patient.”

Section 1233 begins on page 425 of the House’s final draft of the Affordable Care Act. It’s a relatively tiny portion of the law, taking up nine of the bill’s 1,017 pages. It didn’t have much of anything to do with Obamacare’s main goals of expanding coverage or reducing health-care costs.

But Section 1233 became the most politically toxic section of a law rife with contested projects and programs. Section 1233 is where Sarah Palin initially found the so-called “death panels” that would be among the most memorable, and ugly, skirmishes in the Obamacare debate.

Patients, Palin wrote in an August 2009 Facebook post coining the term, “will have to stand in front of Obama’s ‘death panel’ so his bureaucrats can decide … whether they are worthy of health care.” When asked where she found these death panels in the law, Palin’s spokesperson pointed to Section 1233.

But Section 1233 did nothing of the sort (PolitiFact ultimately named “death panels” its lie of the year in 2009). The provision simply allowed Medicare to reimburse doctors when they provided patients an explanation of “the continuum of end-of-life services … including palliative care and hospice.” This wasn’t a death panel. It was an end-of-life care consultation — a conversation where a doctor would tell a patient about his or her options. They could discuss important issues like would the patient prefer to die in the hospital or at home? If there is no treatment left, would they consider hospice care? What are the things they value at the end of life and how can those be achieved? The doctor would not make the decisions for the patient — the patient and family would make up their own minds about how to proceed.

The “death panel” rhetoric quickly became a popular cudgel conservatives used to bash the law. The Independent Payment Advisory Board, for instance, which would have unilateral power to cut Medicare reimbursement rates, became a “death panel.” (The board, meanwhile, has no power to change the type of benefits Medicare provides or which patients get them — it only has authority over what Medicare pays).

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2919326/Screen_Shot_2015-01-09_at_10.43.30_AM.0.png)

The 2009 Sarah Palin Facebook post that coined the term “death panel” (Facebook)

Death panels signs and slogans popped up at town-hall protests across the country; news stories mentioned the term 6,000 times in August and September, Politifact later found. By October, it still came up at least 150 times per week — and Section 1233 was doomed. Legislators saw the backlash and quickly relented. They left the end-of-life planning provision on the cutting-room floor.

The explosive death-panel debate, touched off by the smallest, weakest attempt to talk about the inevitable, shows just how impossible it is for America and the people we send to Washington to have this particular discussion.

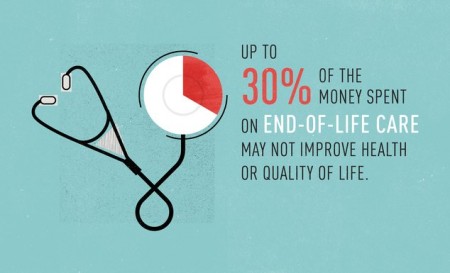

Dying in America is expensive. The six percent of Medicare patients who die each year typically account for 27 to 30 percent of the program’s annual health-care spending. During the last six months of life, the Dartmouth Atlas has found that the average Medicare patient spends 9.9 days in the hospital and 3.9 days in intensive care. Forty-two percent see 10 or more doctors.

In Washington, something so costly typically forces constant conversations about cutbacks and trade-offs and balancing priorities. But with end-of-life care, the opposite tends to be true: we can’t talk about the cost of dying because it sounds like a discussion about rationing. Taking cost into account feels callous and inappropriate in the context of death.

But that’s left, in its place, not a thoughtful approach towards end-of-life care, but a dumb default that pushes everyone — doctors, patients, and families — toward more tests, surgeries, and treatments, no matter the cost in pain and disability to the patient.

The fear at the heart of the death-panel debate was a fear about the loss of autonomy: that a group of anonymous bureaucrats would make the decisions that ought to be reserved for the terminally ill.

That’s a terrible system. No Democrat, Republican, nor any health-policy expert I’ve talked to sees that as the right approach for America.

But they also point out that our haphazard approach to death isn’t especially good at respecting the rights of the dying, either. We don’t like to think about death — and so we don’t. The death-panel debate affirmed that legislating end-of-life issues is terrible politics, so politicians simply avoid it. The result isn’t a more compassionate policy, but a vacuum of policy.

The dearth of debate and discussion doesn’t eliminate the difficult, heart-wrenching decisions that patients, doctors, and their families must make at the end of life. It arguably exacerbates them: not paying doctors to discuss end-of-life issues with Medicare patients, for example, likely means they know less about what patients want at the end of life. By the time the issue simply can’t be ignored, it’s often too late — the patient is already incapacitated or too delirious to articulate his or her priorities.

Much like nursing homes get to decide who eats what, and when, unarticulated end-of-life decisions get outsourced to family members and doctors who make their best guess at what a loved one would have wanted. Patients, in a way, end up living the exact scenario that the death-panel rhetoric made so fearsome: giving over decisions about their last moments of life to another party.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2920092/vox-share__51_.0.png)

There’s a beautiful story that Gawande tells in his book, about a man named Jack Block. At 74, he had to decide whether to undergo a surgery to remove a mass growing on his neck. The procedure ran a 20 percent chance of paralyzing him from the neck down — but without it, the growth would definitely leave him unable to move his legs or arms.

This is the moment, Gawande argues, that there has to be a discussion about what makes life worth living. Gawande interviews his daughter, Susan, who is a palliative-care specialist. And even though this is her line of work, she tells him that the conversation about this surgery was “really uncomfortable:”

We had this quite agonizing conversation where he said — and this totally shocked me — ‘Well, if I’m able to eat chocolate ice cream and watch football on TV, then I’m willing to stay alive. I’m willing to go through a lot of pain if I have a shot at that.’

Susan says this wasn’t the answer she expected; she didn’t even remember her father watching football. But just hearing what mattered — knowing what Jack would consider a life worth living — ended up guiding all further decisions. When Susan’s father developed spinal bleeding, she asked the surgeons: will he be able to watch football and eat ice cream? The answer was yes. They kept going with treatment, until the answer was no.

“Few people have these conversations, and there is good reason for anyone to dread them,” Gawande writes. “They can unleash difficult emotions. People can become angry or overwhelmed. Handled poorly, the conversations can cost a person’s trust. Handled well, they can take real time.”

But these conversations could be the starting point for a health-care system that cares just as well for patients who will heal as those who will not. They’re the place where autonomy gets defined for each patient: whether a life worth living means one where they are able to see friends, or drive their car, or eat chocolate ice cream, or the millions of other things they may hold dear. Those conversations don’t happen now. And as long as that’s the case, all of our autonomy, as we inevitably grow old and become more dependent, is at risk.

Complete Article HERE!

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2400318/sidebar-image__1_.0.jpg)

Famous Hanging Coffin Sites :

Famous Hanging Coffin Sites :