The second year without my husband is in some ways harder than the first.

By Lisa Kolb

On the morning of my third wedding anniversary last Tuesday, or more accurately, the third time I celebrated my first anniversary, I awoke still hugging my husband Erik’s dark green Patagonia fleece. It was his favorite, the one he’s wearing in the photo we used for his memorial service program. I hadn’t needed to sleep with it in a while, but I did that night.

I lay there amid my luxurious new bedding, which, along with my new apartment, was supposed to make his absence feel less acute, since he was never associated with it. I listened to the uncomfortable hum of complete silence, but was too conscious of the day’s significance to go through my normal routine of blasting NPR in the bedroom and the TV in the living room to cut the quiet. I began to cry.

My husband Erik died at age 34 last May, along with five other young men, in a rockfall and avalanche on Mount Rainier. We were married for 19 months.

I talked myself through the motions of breakfast and getting dressed. I wrote out an anniversary card with nowhere to send it, and walked to the old apartment building we shared in Woodley Park back when he was getting his MBA. I sat alone in the shabby linoleum foyer, on top of someone’s Amazon Pantry delivery box, and let memories flood in. I cried some more.

The day ended disastrously, despite the spa treatments and nice dinner with my mom that I thought might shore up the day from being wholly awful. I was upset at the server for bumping into my chair. I was upset that my mother was my dinner partner instead of my husband. I was upset that only a few people had acknowledged the day.

Year One of widowhood, the year when the grief is obvious and raw and ugly, gets all the support and attention. But Year Two is just as hard, and in some ways, it is lonelier.

In the first year, people check in constantly. They call, text, bring food, plan girls’ weekends and excuse — even support — the shuffling around in pajamas crying each day as we wait for the black, hollow feeling to lift.

The Year Two widow, however, is comparatively abandoned to the continued reality of a new and unfamiliar life. We are among the “walking wounded,” those largely without outward signs of trauma (weight regained, estate settled, tears more easily stifled) but who are still under equal, if different, strain.

I had an idea that passing the one-year mark meant the hard part was over, like crossing the finish line of a particularly grueling marathon, or getting to the front of the line at Target on a Saturday. But it is not over.

The one-year anniversary of a spouse’s death is not a benchmark for being healed. It’s merely the day after day 364, followed by 366, 367 and so on. For widows, anticipating relief upon the one-year mark is to be lulled, then hoodwinked, by a false target that implies to others, and even us, that we must be out of the woods, and thus less in need of continued support.

Year One is a struggle merely to eat, merely to get dressed in the morning, merely to think straight while confronting a crushing list of knife-twisting administrative to-dos, like car title transfers and insurance claims and endless calls to robotic customer service reps to tell them to cancel your husband’s account/subscription/delivery because he is dead.

By Year Two, those things are largely resolved. No small feat, yet it is all replaced by an equally daunting, though less obvious, list of second year to-dos, like learning to live with a new, solo identity after years of partnership. Like knowing that other people must think you should be functioning and working at a back-to-normal level again, and being ashamed and frustrated that you are just not. Like facing the immutable truth that he is still — still! — gone, always will be, and there is nothing you can do about it.

In other words, if Year One of widowhood is a struggle for survival, Year Two is the equally difficult struggle to begin living life again. It is hard. Our spouses just keep being dead.

Some days I do not care about anything. Some days, I am tired — tired of fighting my way forward, tired of feeling untethered, tired of not knowing how to configure the printer, tired of figuring out all the finances, tired of needing the television on, tired of taking the trash out myself, tired of still having to cancel his mail, tired of everyone else having a spouse, tired of missing Erik. Just tired.

Sometimes I’m ambushed by the sight of someone who looks like Erik. It happened most recently on a sunny afternoon last month. I was walking down Connecticut Avenue to pick up allergy medicine at CVS, debating a detour into Krispy Kreme, when I caught sight of a man walking across Dupont Circle. He had Erik’s same lanky build, sandy blond hair and preppy style, right down to the tailored, pale pink collared shirt. I could not help myself and began following the man down Connecticut, then left onto N Street, sobbing behind my sunglasses, allowing myself the indulgence of imagining, just for a moment, that it was Erik walking around like everyone else, off to work or maybe his CrossFit class. When the man turned the corner onto 17th Street I let him go, realizing that on balance, it was probably less unhealthy to eat a donut than chase a ghost.

Bedtime alone is still hard. When I awaken in the middle of the night in a lonely panic, I listen to audiobooks or watch Netflix despite my and Erik’s strict no-devices-in-bed policy until my mind drifts to the story and away from my endless loop of “what will I do with the rest of my life … why can’t you be stronger and just go to the bank already to close his account … don’t forget to send Erik’s grandfather his baseball hat …”

It is a common refrain among widows that support tends to fall way off after a year. I wish more friends and family would reach out like they did early on. One friend used to send texts containing nothing more than emoji hearts, but it was enough. Some sent me articles or books they thought might help; others called to take me to lunch or dinner. Eating across from an empty chair — and knowing the reason for the empty chair — is difficult. Always initiating plans is tiring.

I want someone to really ask how I am doing, and say Erik’s name or talk about him freely. It keeps him alive. I know people are trying not to upset me by bringing him up, but I promise, he is already on my mind.

I do not blame my friends for their increased absence. Supporting a grieving friend long term requires time and stamina — intangibles already in short supply. There’s an emotional limit, as friends and family look to return to the safety of equilibrium. There’s also an intellectual limit: How could others understand the breadth of such a loss unless they have gone through it? Spousal grief is like Vegas: One must experience it personally to really understand how huge and overwhelming it is.

Some things are better, though. I regained the 10 pounds I dropped when Erik died and I could not eat. I feel strong enough to take ballet class again, after months of being too weak and sad to exercise. I socialize more readily. I laugh. I still cry, but the tears fall days apart, rather than hours; I no longer feel the need to add tissues to my wallet/keys/phone/lip balm check before I leave the house. I was able to clear out some — though not all — of Erik’s drawers. I have found some peace, and learned to accept the loss.

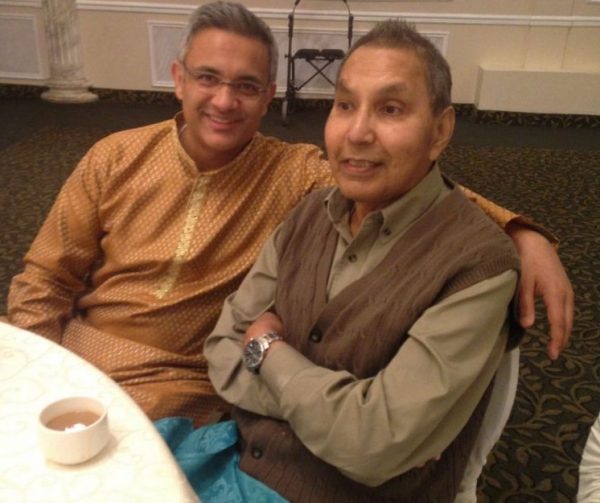

I am now dating Brodie, a widower. Uncannily, Brodie’s wife’s memorial service was on the same day as Erik’s, so what began as a supportive friendship through a shared timeline of grief has blossomed into something happy and wholly our own. But there are complications. I worry that he, too, could suddenly die young — perhaps an accident or fluke heart attack — and must give myself a pep talk every time he takes a flight, goes mountain biking or does not call or text immediately at an appointed hour.

I initially told no one we were dating. I am still sometimes reluctant to tell people, out of fear that they’ll think I no longer need support. I am afraid of being judged: Maybe it’s too soon, maybe people will think I am “over” Erik, maybe people will stop talking about him. But I will never be “over” Erik. Widowhood is sort of like being an amputee: Over time, the wound heals over, and I will learn to function well without my missing limb, but there will always be a vital part of me missing.

Later this evening, I will eat dinner alone and go to ballet class. I will go not because I am particularly in the mood, but because I know a step forward begins with a step out the door. I will go because Erik would want me to go and I want to be okay again — for him, for me, for Brodie, for my family. I am still rusty after not dancing for such a long time; my pliés are shallow and my pirouettes are off balance. But I am dancing again, and striving to get better every day.

The widow’s journey is a complicated and lengthy one. Awareness of that length — by us and by others — helps make it survivable. By acknowledging the loss’ enormity, we can forgive ourselves for continued stumbles and setbacks. I hope our family and friends can likewise know to be there to help us rise.

As I walk to my car after class, I will look up to the night sky and I will tell him, as I often do, “I am trying my very best, love.”

Complete Article HERE!