“Am I dying?” The honest answer.

[M]atthew O’Reilly is a veteran emergency medical technician on Long Island, New York. In this talk, O’Reilly describes what happens next when a gravely hurt patient asks him: “Am I going to die?”

The Amateur's Guide To Death & Dying

Enhancing Life Near Death

[W]e can’t control if we’ll die, but we can “occupy death,” in the words of Peter Saul, an emergency doctor. He asks us to think about the end of our lives — and to question the modern model of slow, intubated death in hospital. Two big questions can help you start this tough conversation.

[A]t the end of our lives, what do we most wish for? For many, it’s simply comfort, respect, love. BJ Miller is a hospice and palliative medicine physician who thinks deeply about how to create a dignified, graceful end of life for his patients. Take the time to savor this moving talk, which asks big questions about how we think on death and honor life.

[I]n this short, provocative talk, architect Alison Killing looks at buildings where death and dying happen — cemeteries, hospitals, homes. The way we die is changing, and the way we build for dying … well, maybe that should too. It’s a surprisingly fascinating look at a hidden aspect of our cities, and our lives.

By ANN NEUMANN

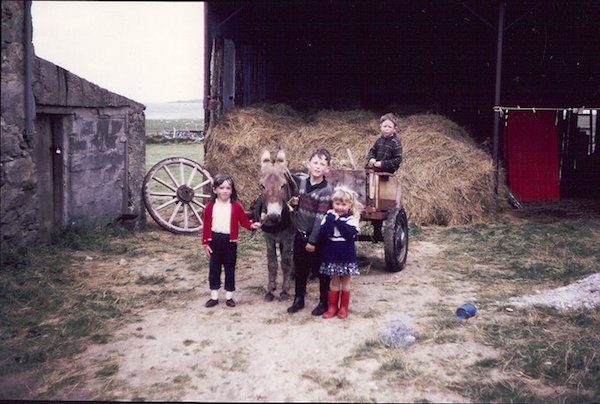

MY FATHER’S WAKE

How the Irish Teach Us How to Live, Love and Die

By Kevin Toolis

275 pp. Da Capo. $26.

[I]n his 2015 book “The Work of the Dead,” Thomas W. Laqueur takes up an ancient question: Why do we care for the bodies of the dead when we know that after our loved ones have left them they are empty shells? He begins his query with Diogenes, the eccentric fourth century B.C. philosopher who requested that his dead body be thrown over the city walls to be devoured by beasts. The corpse may be waste, “meat gone mad,” James Joyce wrote in “Ulysses,” but since our beginnings we have endowed corpses with cultural and symbolic significance. “Whatever our religious beliefs, or lack of belief, we share the very deep human desire to live with our ancestors and with their bodies. We mobilize their power,” Laqueur wrote.

The journalist Kevin Toolis does not doubt that corpses have particular superpowers. In his new book, “My Father’s Wake,” the bodies of our dead are life lessons, moral instructors of how to have satisfying lives and peaceful deaths. The tradition of the Irish wake, with rituals that predate Christianity, is our legend, “the best guide to life you could ever have,” he writes.

“My Father’s Wake” is at heart a memoir, chronicling a childhood spent between Edinburgh and remote Achill Island off the western coast of Ireland’s County Mayo, where his parents were born. When Toolis is 19, his brother Bernard dies of leukemia. He is his brother’s keeper, a bone marrow donor, but the transplant fails. The trauma sends Toolis as a young reporter out into the world, from Somalia to Afghanistan, in search of death, disease, famine and war. “I was grieving,” Toolis writes. “Not for my dead brother but for the young man who died with him and lost his mortal innocence. Me.”

The contrast between young Bernard’s death (in the city, in the care of what Toolis calls the “Western Death Machine”) and his father Sonny’s death (at home in old age on Achill) sets up Toolis’s castigation of modern medicine and death rites. But it is Toolis’s fine skill at showing the means and aftermath of death rather than his prescription for how to improve dying that most animates “My Father’s Wake.”

“Under the greenish light of a fluorescent tube, Eliza’s hands writhed involuntarily at her wrist as if seeking to escape their dying host,” he writes of a 20-year-old Malawian girl who dies in the middle of the night of AIDS. In the local dialect, Toolis tells us, the disease is known as matantanda athu omwewa, “this thing we all have in common.” Toolis’s writing is so visceral and profound when he is near dying bodies that the lessons of such experiences become evident — so evident, indeed, that the unfortunate framing of “My Father’s Wake” as a how-to for urban Westerners feels a bit clumsy and redundant.

“Under the greenish light of a fluorescent tube, Eliza’s hands writhed involuntarily at her wrist as if seeking to escape their dying host,” he writes of a 20-year-old Malawian girl who dies in the middle of the night of AIDS. In the local dialect, Toolis tells us, the disease is known as matantanda athu omwewa, “this thing we all have in common.” Toolis’s writing is so visceral and profound when he is near dying bodies that the lessons of such experiences become evident — so evident, indeed, that the unfortunate framing of “My Father’s Wake” as a how-to for urban Westerners feels a bit clumsy and redundant.

Early in the book, Toolis implores us to face our mortality by calculating the date of our death, “the end point for you.” In the book’s final chapter, “How to Love, Live and Die,” he offers this advice: “If you can find yourself a decent Irish wake to go to, just turn up and copy what everyone else is doing,” and “take your kids along too if you can.”

These bookends undermine Toolis’s manifest intellectual curiosity about contemporary medical and funerary practices. Studies indeed show that when dying patients plan for and accept their impending death, their family members more ably manage grief, but Toolis never sheds light on why that is. Nor does he identify where or how the funeral industry — “the dismal trade,” as Jessica Mitford called it in 1963 — has gone wrong. Grievers in funeral homes touch their corpses too.

I can’t help wishing that Toolis had kept the beautiful memoir of his life-and-death experiences and thrown the self-help curriculum over the city walls to be devoured by beasts. There really is no greater truth than a corpse.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Not quite a year ago, I did the hardest thing in the world: I watched my beloved partner and best friend die. Benjamin had been struggling with illness for 18 months at that point. It had been 9 months since we’d received word that the problem was cancer, and six months since we’d heard there was nothing more the doctors could do.

On the morning of May 2, 2017, I lay next to him in bed and told him I was starting to worry he was leaving us. He nodded his head slowly and said he agreed. Laboriously, drifting in and out of consciousness, he was able to express his final thoughts.

“As I see it,” he said, “there is nothing left to be done.” Less than two hours later, he was gone.

Looking back, the story I most want to tell about this time is not the story of his dying. It’s the story of what happened after he died. For in the moments, hours and days after he took his last breath, we—his family, friends and I—took an unconventional path. Unconventional, but in no way new. We took a path that is ancient and rich and deeply felt, that is simple and real and human. We did everything ourselves, at home.

The story starts a few years ago, on Facebook of all places. I was scrolling through my feed when I saw an acquaintance had posted about her mother’s death—including pictures of her body, wrapped in a gauzy shroud. I was transfixed.

This friend and her sister had been with her mother while she died at home, and had cared for her body themselves—washing and anointing her, and then dressing her in her favorite clothes. She said they had been instructed in the process by someone called a “death midwife.”

“That,” I thought. “That is what I want to do for my loved ones, when the time comes.” I filed away the words “death midwife” and “home funeral” and mostly forgot about it.

Until the day Benjamin went in for his liver transplant, and instead was told the cancer had spread. That it was inoperable and terminal. The first thing I did after we left the hospital was Google death midwives near Malibu, which was where we were living at the time. Up came an organization called Sacred Crossings. Its founder, Olivia Bareham, quickly became an invaluable guide.

After going through it myself, I can also say that it is a profound gift to be able to lie next to your loved one’s body, to hold their hand, or to simply look at them, for hours or days after they die. It signals to the subconscious parts of you that the death has really happened. It is healing and whole-making, and to me has come to feel like an essential part of the grieving process.

We relocated from Malibu to Napa three months before Benjamin died. Olivia helped us find a local death doula who helped us make preparations with the cemetery where Benjamin would be cremated. I never spoke to the funeral director; everything was arranged for us by the doula. As a result, I could focus all of my attention on being with Benjamin in his last days and hours.

The day he died, I didn’t have to talk to a single stranger. I didn’t have to leave his side until I, myself, was ready. Undertaking a ritual as old as the world, his closest women friends and I washed his body. We anointed it with frankincense and lavender oils. We dressed him in his favorite clothes.

I slept in the room with his body all three nights we kept him at home. I spent a lot of time lying next to him, crying. So did his family members and dear friends. Even his twin 9-year-old boys came and sat by his bedside, starting what will no doubt be a lifelong process of integrating the impossible fact that Papa is really gone.

We had a gathering at our home the third night, where 60 people came to say goodbye. Benjamin’s body was in a candle-lit bedroom, and friends could choose to visit it or not. (Most did, including many children.) The doula provided us with a cardboard cremation box, which our friends and family members decorated with beautiful wishes for Benjamin. We told stories and ate food and cried together. His friends sang songs and read poems. We shared his death in community, in our home.

One friend told me that night, “My relationship to death has completely changed, just being here tonight.” Several others have approached me since, to express similar sentiments.

The decision to do death in one’s home is huge, and so obvious once you remember how humans have been doing it since the dawn of time.

Caring for our loved ones’ bodies in death is our birthright. It is not a job we need to outsource. Unless we want to—and that’s fine, too. There is no right or wrong here. What I didn’t know before this experience is that each of us has a choice, and I want everyone else to know that, too.

After three days, my heart was quietly ready for his body to move on. This peace could not have crept in, had he been taken from me moments after he died. I could see, as a dear friend put it, that he was beginning to “melt back into the earth.” The rhythm of life was telling us the time had come.

The next morning, family and close friends gathered early and prayed over Benjamin’s body. We lifted him up and laid him gently in the decorated box, covering his body with a soft blanket and fresh flowers. His brothers carried him down the stairs, and slid the box into the back of his beloved truck.

We drove to the funeral home, where our death doula was waiting with the funeral director. When I popped open the back window of the camper shell and revealed not only Benjamin’s casket, but also his twin boys, their mom and myself riding in the truck bed, the funeral director shook his head.

“This is highly unusual,” he said. We all laughed.

“We are a highly unusual bunch,” I agreed. (I will be forever grateful to that funeral director for keeping such an open mind.)

We had what’s called a “viewing cremation,” which is available but not advertised at many mortuaries. This means the family members get to roll the body into the cremation oven, close the door and press the buttons that begin the incineration process. (A deep bow to author Mirabai Starr, and her gorgeous memoir Caravan of No Despair, for teaching me that viewing cremations are possible.) There were a dozen family members standing around as Benjamin’s Grammy, his boys and I all pressed the button together.

We never left him. From the moment he died until the moment his body returned to ashes, his loved ones were by his side.

All of this does not “make everything better.” I still mourn for Benjamin every single day. I still cry and feel angry and even hopeless sometimes. But I feel entirely peaceful about the way we celebrated his exit. We did it in a way that was deeply true. True to myself, true to Benjamin, true to his clan of family and friends.

Our midwife Olivia says that people die how they lived. What if the converse is also true—that we can only embrace life to the degree that we embrace death? If that’s the case, what does it mean if we push death away, ask someone else to take care of it for us, and categorize it as ugly, vulgar and terrifying?

It’s my belief that the time has come to do death a different way. It’s time to learn how to be with it—and, as a result, to love it. And we do this by embracing death, by changing how we celebrate it, by relinquishing the taboos, and by bringing dying out into the open. We do it, I believe, by returning to the old ways. By keeping the celebration of death close to our hearts, and—if it feels right—in our very homes.

When we do, we are not only embracing death. We are embracing life. We are becoming more fully human by learning to say goodbye differently. By loving each other in death, we are loving life—all the way to the very end.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

[T]hese days, everyone from poets to professors, priests, and everyday folks all opine about what makes a “good death.” In truth, deaths are nearly as unique as the lives that came before them — shaped by the combination of attitudes, physical conditions, medical treatments and people involved.

“A good death can, and should, mean different things to different people,” says Haider Warraich, MD, author of “Modern Death – How Medicine Changed the End of Life.” “To me, it means achieving an end that one would have wanted, and that can really mean anything – from being in the intensive care unit, getting all sorts of life-sustaining therapies, to being at home, surrounded by family, getting hospice care.”

Still, many have pointed to a few common factors that can help a death seem good — and even inspiring — as opposed to frightening, sad, or tortuous. By most standards, a good death is one in which a person dies on his own terms, relatively free from pain, in a supported and dignified setting.

“I think what makes a good death is really different for every individual, but there are some common threads that occur with each person I’ve seen,” says Michelle Wulfestieg, executive director of the Southern California Hospice Foundation (SCHF) and author of “All We Have is Today: A Story of Discovering Purpose.”

Some of patients’ most common end-of-life priorities include being at peace spiritually, knowing that they have the support of loved ones, having their affairs in order and being reassured that they won’t have a painful death, says Wulfestieg, who has worked in hospice care for 14 years.

Not everyone has the luxury of planning for death. But those who take the time and make the effort to think about their death in advance and plan for some of the details of their final care and comfort are more apt to retain some control and say-so in their final months, weeks and days.

Legal specifics of such planning can include taking steps to get affairs in order by:

For those considering hospice care at the end of life, another crucial end-of-life planning step is to elect the hospice benefit under Medicare, notes Joseph Shega, MD, national medical director for national hospice care provider VITAS Healthcare. He points out that hospice care is covered by Medicare, along with most health insurance providers.

Richard Averbuch, Executive Director of the Massachusetts Coalition for Serious Illness Care, cautions not to wait until a serious illness or crisis before planning for end-of-life care.

“The best time to name a proxy and talk about your preferences is now – whatever your stage of life. Think of it as part of your overall wellness program – just as important as preventive care, an exercise regime, and a good diet,” he says. “And you need to revisit the conversations periodically, since your feelings may change as you age or as your health status changes.”

Most Americans say they would prefer to die at home, according to recent polls. Yet the reality is that some three-quarters of the population dies in some sort of medical institution, many of them after spending time in an intensive care unit.

Part of that may be due to misunderstandings about the different options for treating a patient’s pain in their final days.

“There are still people who are uncomfortable with the use of pain medications at the end of life, even as their use is essential for the patients who are in pain,” says Warraich.

As life expectancies increase, more people are becoming proactive. A growing number of aging patients are choosing not to have life-prolonging treatments that might ultimately increase pain and suffering — such as invasive surgery or dialysis — and deciding instead to have comfort or palliative care through hospice in their final days.

Along with the practical matters of having one’s affairs in order, it’s equally important to prepare for death emotionally, to spend time with loving people toward the end of life, and to have spiritual sustenance.

“Patients really want to know that their life had purpose, that they made a difference and that their lives mattered,” says Wulfestieg. “It has to do with family a lot of times, saying those I love yous and goodbyes.” The SCHF often works to reunite dying patients with family members,

including those who have long been estranged.

Often quoted among hospice care providers and in the literature on death and dying are the tenets in “The Four Things That Matter Most“, by Ira Byock, a medical doctor who professes the need for a dying person to express four thoughts at the end of life:

At the time Caring.com spoke with Wulfestieg, her organization was preparing to reunite Marilyn, a woman with ovarian cancer and only a few weeks to live, with her three estranged adult children and grandchildren.

Due to Marilyn’s problems with drugs, alcohol and crime, all three of her children grew up in foster care, and she’d lost contact with them. Her dying wish was to have a family meal with her children and grandchildren, so SCHF have arranged to fly out Marilyn’s family members to make it happen, Wulfestieg says.

“That’s really her dying wish, to be able to say ‘I’m sorry, I love you and goodbye,’” she says. “It’s really a story of grace and forgiveness and hope.”

The right company can help aid a “good death.” Although dying may be scary or sad or simply unfamiliar to those who are witnessing it, studies of terminally ill patients underscore one common desire: to be treated as live human beings until the moment they die.

Most also say they don’t want to be alone during their final days and moments. This means that caregivers should find out what kind of medical care the dying person wants administered or withheld and be sure that the medical personnel on duty are fitting in skill and temperament.

“Before health care decisions around end-of-life care can be delineated, clinicians and patients must first recognize when life-limiting conditions such as heart failure, lung disease or cancer are no longer responding to disease-modifying treatment,” Shega says. Next, he says, there should be “a conversation between the patient and clinician about end-of-life care and the role of hospice.” He adds that care teams need to provide ongoing support to the patient and their loved ones throughout their final days, “never abandoning the patient and respecting their choices.”

Favorite activities or objects can be as important as final medical care. Caregivers should ascertain the tangible and intangible things that would be most pleasing and comforting to the patient in the final days: favorite music or readings, a vase of flowers, a back rub or foot massage, being surrounded by loved ones in quiet or conversation.

Spirituality can help many people find strength and meaning during their final moments. Think about the patient’s preferred spiritual or religious teachings and underpinnings, since ensuring access to this can be especially soothing at the end of life.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!