Literary Lessons on Death and Dying

By

For over three decades, Reverend F. Washington Jarvis served as headmaster of Boston’s Roxbury Latin School, the oldest school in continuous existence in North America. During this time, Jarvis delivered a series of addresses to the student body, the best of which were collected in “With Love and Prayers: A Headmaster Speaks to the Next Generation.” For a number of years, I taught “With Love and Prayers” to high schoolers and found that both parents and students valued the book for its wisdom, wit, and moral lessons.

In his chapter “The Spiritual Dimension,” Jarvis relates this anecdote to the young men in his charge:

The celebrated headmaster of Eton College, Cyril Alington, was once approached by an aggressive mother. He did not suffer fools gladly.

“Are you preparing Henry for a political career?” she asked Alington.

“No,” he said.

“Well, for a professional career?

“No,” he replied.

“For a business career, then?”

“No,” he repeated.

“Well, in a word, Dr. Alington, what are you here at Eton preparing Henry for?”

“In a word, madam? Death.”

As Jarvis then points out, the principal mission of Roxbury Latin is to prepare its students for life. “And,” he goes on, “the starting point of that preparation is the reality that life is short and ends in death.”

These few lines bring much to consider. Do we aim at getting our young people into “good” schools while neglecting to instill in them the classical virtues? Do we recognize that “life is short and ends in death”? If so, what outlook on the world should such a truth inculcate?

Before seeking answers to these questions, we must recognize that our ancestors were more familiar with death than we moderns. They lived among the sick and dying in ways we do not, and were forced to deal with circumstances that today are the domain of our health professionals. Victorian poetry, for example, is a thicket of verse about death and dying.

We are more distant from the dying. Low infant mortality rates have thankfully removed many of us from witnessing those tragedies, and though a majority of Americans want to die at home, only 20 percent do so.

Lacking this intimacy with the death of earlier generations, we may, if we wish greater familiarity, turn to literature, Victorian or otherwise. Stories and poems can give us intimate portraits of the hope and the despair, the joy and the sorrow, the courage and fear of the dying and those who surround them.

Let’s look at four novels in which the characters exit this earth in dramatically different ways. Each of them offers a lesson on death.

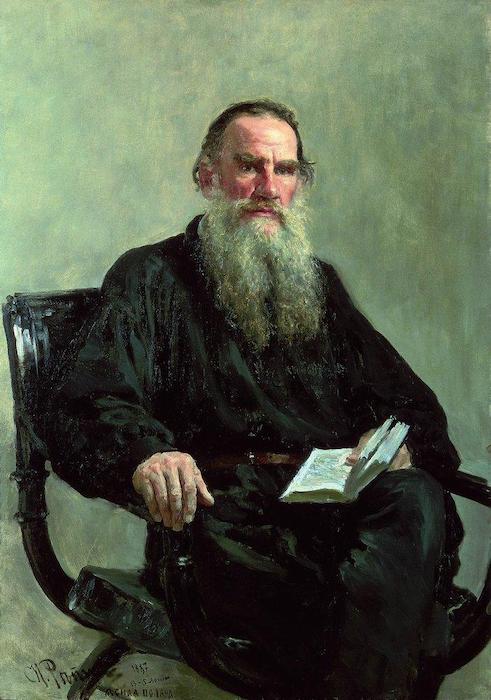

‘The Death of Ivan Ilyich’

In “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” Leo Tolstoy’s novella and perhaps the greatest of all fictional meditations on the debt we owe to nature, Ivan Ilyich lies on his deathbed wondering whether he has lived a good life.

As doubts fill him, and as death creeps ever closer, he suddenly realizes that “though his life had not been what it should have been, this could still be rectified.” In his last hours, he is flooded with sorrow and pity for the son and wife he has neglected, and though they cannot understand him when he begs their forgiveness, he dies “knowing that He whose understanding mattered would understand.”

Ivan Ilyich goes to his grave in peace, knowing the truth of Katharine Tynan’s lines from “The Great Mercy”: “Betwixt the saddle and the ground/was mercy sought and mercy found.”

Here Tolstoy reminds us that even on our deathbed, we may yet clear our conscience and set right those things that we have done or failed to do.

‘Kristin Lavransdatter’

In Sigrid Undset’s trilogy of medieval Norway, “Kristin Lavransdatter,” we discover the importance of ritual in death. The Christian injunction “To bury the dead” means more than tumbling a corpse into a grave, covering it over with earth, and moving on. During the long death of Kristin’s father, Lavrans, the neighbors visit, the priest performs the last rites, a vigil is held after Lavrans breathes his last, and later there is a feast to celebrate his memory.

From Kristin and her kin, we moderns might learn once again how to “bury the dead.” More and more, I hear of people and know a few of them who when a loved one dies, conduct no ritual of passage, no funeral, no memorial service. An obituary may appear in the paper, or not, but otherwise the survivors put the deceased into the grave or columbarium without ceremony.

With this practice, we fail to realize that we have cheated ourselves of the comfort of a formal farewell and have tarnished our humanity in the bargain.

‘A Tale of Two Cities’

In “A Tale of Two Cities,” Charles Dickens puts Sydney Carton, a barrister, an alcoholic, and a cynic, onto the platform of a guillotine after Carton nobly takes the place of another man sentenced to die by execution. Carton’s thoughts before the fall of the blade bring him solace: “It is a far, far better thing I do than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

From Carton, we receive a lesson in courage when faced with death.

‘Little Women’

Of course, as Louisa May Alcott notes in “Little Women,” “Seldom except in books do the dying utter memorable words, see visions, or depart with beatified countenances …”

In describing the passing of young Beth March, whose “end comes as naturally and simply as sleep,” Alcott shows her readers that, like Sydney Carton, those who die possess the power to bequeath gifts to the living. Before she slips into the shadows, Beth reads some lines written by her beloved sister Jo. And she realizes that her illness and impending death have caused Jo, her caretaker, to grow and mature, and to take from her lessons in bravery and her “cheerful, uncomplaining spirit in its prison-house of pain.”

Like in these novels, the loved ones with whom I have sat while they closed their eyes and faded away have given me instruction. Perhaps the best of these teachers was my mother, who died from cancer 30 years ago. In her final lesson—perhaps her greatest lesson—she taught me and my brothers and sisters by way of example how to die with grace and courage.

If I find myself in my mother’s circumstances, with time to bid goodbye to those I love, and if I possess even half of her strength, I will die a fortunate man.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!