For decades, Americans have been urged to fill out documents specifying their end-of-life wishes before becoming terminally ill—living wills, do-not-resuscitate orders, and other written materials expressing treatment preferences.

Now, a group of prominent experts is saying those efforts should stop because they haven’t improved end-of-life care.

“Decades of research demonstrate advance care planning doesn’t work. We need a new paradigm,” said Dr. R. Sean Morrison, chair of geriatrics and palliative medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and a co-author of a recent opinion piece advancing this argument in JAMA.

“A great deal of time, effort, money, blood, sweat and tears have gone into increasing the prevalence of advance care planning, but the evidence is clear: It doesn’t achieve the results that we hoped it would,” said Dr. Diane Meier, founder of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, a professor at Mount Sinai and co-author of the opinion piece. Notably, advance care planning hasn’t been shown to ensure that people receive care consistent with their stated preferences—a major objective.

“We’re saying stop trying to anticipate the care you might want in hypothetical future scenarios,” said Dr. James Tulsky, who is chair of the department of psychosocial oncology and palliative care at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and collaborated on the article. “Many highly educated people think documents prepared years in advance will protect them if they become incapacitated. They won’t.”

The reasons are varied and documented in dozens of research studies: People’s preferences change as their health status shifts; forms offer vague and sometimes conflicting goals for end-of-life care; families, surrogates and clinicians often disagree with a patient’s stated preferences; documents aren’t readily available when decisions need to be made; and services that could support a patient’s wishes—such as receiving treatment at home—simply aren’t available.

But this critique of advance care planning is highly controversial and has received considerable pushback.

Advance care planning has evolved significantly in the past decade and the focus today is on conversations between patients and clinicians about patients’ goals and values, not about completing documents, said Dr. Rebecca Sudore, a professor of geriatrics and director of the Innovation and Implementation Center in Aging and Palliative Care at the University of California–San Francisco. This progress shouldn’t be discounted, she said.

Also, anticipating what people want at the end of their lives is no longer the primary objective. Instead, helping people make complicated decisions when they become seriously ill has become an increasingly important priority.

When people with serious illnesses have conversations of this kind, “our research shows they experience less anxiety, more control over their care, are better prepared for the future, and are better able to communicate with their families and clinicians,” said Dr. Jo Paladino, associate director of research and implementation for the Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs, a research partnership between Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Advance care planning “may not be helpful for making specific treatment decisions or guiding future care for most of us, but it can bring us peace of mind and help prepare us for making those decisions when the time comes,” said Dr. J. Randall Curtis, director of the Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence at the University of Washington.

Curtis and I communicated by email because he can no longer speak easily after being diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, an incurable neurologic condition, early in 2021. Since his diagnosis, Curtis has had numerous conversations about his goals, values, and wishes for the future with his wife and palliative care specialists.

“I have not made very many specific decisions yet, but I feel like these discussions bring me comfort and prepare me for making decisions later,” he told me. Assessments of advance care planning’s effectiveness should take into account these deeply meaningful “unmeasurable benefits,” Curtis wrote recently in JAMA in a piece about his experiences.

The emphasis on documenting end-of-life wishes dates to a seminal legal case, Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, decided by the Supreme Court in June 1990. Nancy Cruzan was 25 when her car skidded off a highway and she sustained a severe brain injury that left her permanently unconscious. After several years, her parents petitioned to have her feeding tube removed. The hospital refused. In a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the hospital’s right to do so, citing the need for “clear and convincing evidence” of an incapacitated person’s wishes.

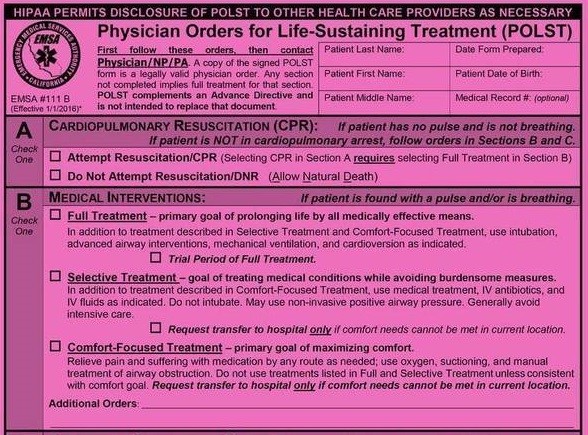

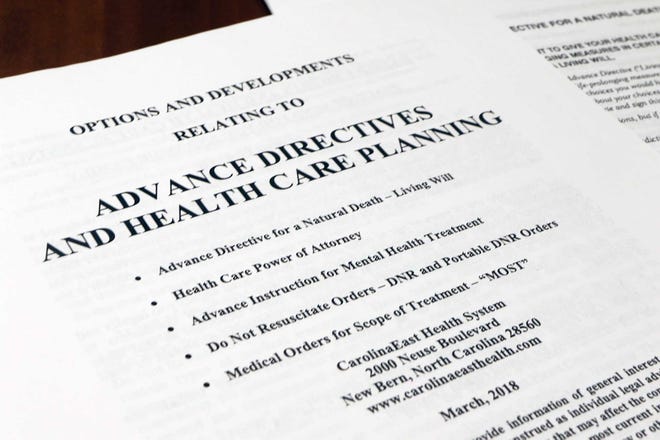

Later that year, Congress passed the Patient Self-Determination Act, which requires hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, health maintenance organizations, and hospices to ask whether a person has a written “advance directive” and, if so, to follow those directives to the extent possible. These documents are meant to go into effect when someone is terminally ill and has lost the capacity to make decisions.

But too often this became a “check-box” exercise, unaccompanied by in-depth discussions about a patient’s prognosis, the ways that future medical decisions might affect a patient’s quality of life, and without a realistic plan for implementing a patient’s wishes, said Meier of Mount Sinai.

She noted that only 37 percent of adults have completed written advance directives, which in her view is a sign of uncertainty about their value.

Other problems can compromise the usefulness of these documents. A patient’s preferences may be inconsistent or difficult to apply in real-life situations, leaving medical providers without clear guidance, said Dr. Scott Halpern, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine who studies end-of-life and palliative care.

For instance, an older woman may indicate she wants to live as long as possible and yet also avoid pain and suffering. Or an older man may state a clear preference for refusing mechanical ventilation but leave open the question of whether other types of breathing support are acceptable.

“Rather than asking patients to make decisions about hypothetical scenarios in the future, we should be focused on helping them make difficult decisions in the moment,” when actual medical circumstances require attention, said Morrison, of Mount Sinai.

Also, determining when the end of life is at hand and when treatment might postpone that eventuality can be difficult.

Morrison spoke of his alarm early in the pandemic when older adults with COVID-19 would go to emergency rooms and medical providers would implement their advance directives (for instance, no CPR or mechanical ventilation) because of an assumption that the virus was “universally fatal” to seniors. He said he and his colleagues witnessed this happen repeatedly.

“What didn’t happen was an informed conversation about the likely outcome of developing COVID and the possibilities of recovery,” even though most older adults ended up surviving, he said.

For all the controversy over written directives, there is strong support among experts for another component of advance care planning—naming a health care surrogate or proxy to make decisions on your behalf should you become incapacitated. Typically, this involves filling out a health care power-of-attorney form.

“This won’t always be your spouse or your child or another family member: It should be someone you trust to do the right thing for you in difficult circumstances,” said Tulsky, who co-chairs a roundtable on care for people with serious illnesses for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

“Talk to your surrogate about what matters most to you,” he urged, and update that person whenever your circumstances or preferences change.

Most people want their surrogates to be able to respond to unforeseen circumstances and have leeway in decision-making while respecting their core goals and values, Sudore said.

Among tools that can help patients and families are Sudore’s Prepare for Your Care program; materials from the Conversation Project, Respecting Choices and Caring Conversations; and videos about health care decisions at ACP Decisions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also has a comprehensive list of resources.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!