Cecelia Clayton, MPH, is the executive director at Karen Ann Quinlan Hospice.

Q: How can I learn more about advance directives/advance care planning?

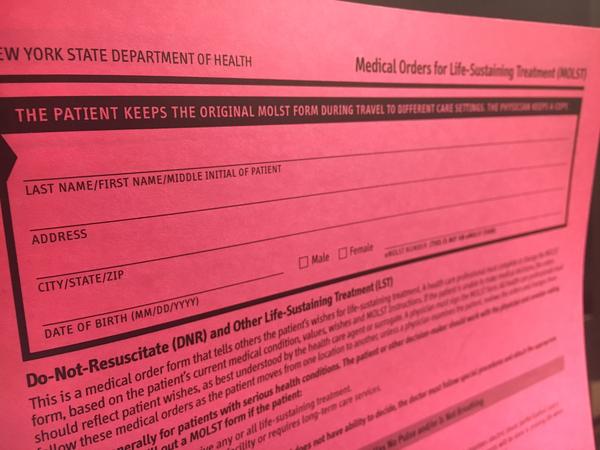

A: During National Hospice Month it’s important to know your options. All adults can benefit from thinking about what their health care choices would be if they are unable to speak for themselves. These decisions can be written down in an advance directive so that others know what they are. Advance directives come in two main forms:

Proxy Directive (Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare)

A proxy directive is a document you use to appoint a person to make healthcare decisions for you in the event you become unable to make them yourself. This document goes into effect whether your inability to make healthcare decisions is temporary because of an accident or permanent because of a disease. The person that you appoint is known as your “healthcare representative” and they are responsible for making the same decisions you would have made under the circumstances. If they are unable to determine what you would want in a specific situation they are to base their decision on what they think is in your best interest.

Instruction Directive (Living Will)

An instruction directive is a document you use to tell your physician and family about the kinds of situations you would want or not want to have life-sustaining treatment in the event you are unable to make your own healthcare decisions.

You can also include a description of your beliefs, values, and general care and treatment preferences.

This will guide your physician and family when they have to make healthcare decisions for you in situations not specifically covered by your advance directive.

Advance Directive: Your Right to Make Health Care Decisions

You have the right to:

- Ask questions about your care.

- Completely understand your medical condition.

- Accept or refuse any treatments.

- Make future decisions by completing an advance directive.

- If you have a life-limiting illness — you have the right to choose the hospice of your choice.

Karen Ann Quinlan Hospice has ready-made packets with current Living Will information available at no charge. The packets can be picked up at the desk at the hospice office at 99 Sparta Ave, in Newton, or call the hospice at 973-383-0115, or at 800-882-1117 to have one mailed to you.

Free seminar

More information will be available at the “Ask An Elder Law Attorney” seminar that will be held from 10:30 to 11:30 a.m., Dec. 8 at the Pike County Public Library in Milford, Pa.

The event is free to the public and light refreshments will be served.

Attendees will be able to ask questions about elder care, estate planning, living trust, last will and testament, advance directives and more. For more information, visit www.KarenAnnQuinlanHospice.org/Seminar.

Here is a checklist to consider to plan ahead or if you need help now.

- Get the information you need to make informed choices about end-of-life care.

- Get to know end-of-life care services that are available, such as hospice and palliative care providers.

- For information, visit the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization’s website: www.nhpco.org

- Discuss your thoughts, concerns and choices with your loved ones.

- Talk to your doctor about different treatments.

- Establish advance directives (a living will and medical power of attorney) for your state.

- Talk to your healthcare agent, family and doctor about your choices.

- Discuss your choices often, especially when your medical condition changes.

- Keep your completed advance directives in an accessible place.

- Give photocopies of the signed originals to your healthcare agent, alternate agents, doctor, family, friends, clergy and anyone else who might be involved in your healthcare.

- Assess your financial situation, create a financial inventory and determine what end-of-life goals you want to accomplish that involve money.

- Learn about the cost of end-of-life care, how medical bills and expenses will be paid for if you are not able to.

- Make financial decisions such as how you want to give your money and possessions to others upon your death.

- Prepare for the time when you cannot handle money matters; appoint a durable power of attorney.

- Plan your funeral/memorial service.

The living will is a direct result of the Karen Ann Quinlan landmark case won by Joseph and Julia Quinlan in 1976 on behalf of their daughter, Karen Ann.

Complete Article HERE!