Don’t Neglect the Softer Side of Your Estate Plan

[A]s my family’s “first responder” and resident financial person, I served as power of attorney for my parents, as well as executor and trustee for both.

Their estate-planning documents attended to a lot of crucial issues: the distribution of their assets, the trusts that were to be set up upon each of their deaths, and their attitudes toward life-sustaining care.

Yet having gone through the process of seeing my parents through their last years and settling their estates, I’m struck by the number of “softer” decisions these documents didn’t cover–important topics like their attitudes toward receiving care in their home or in a facility, or whether they’d prefer to die at home or if a hospital was OK. Did I need to split up all of the physical assets equally among the children, or were they OK with me letting more stuff go to family members with a greater need for them?

Implicit in making someone an executor, trustee, or guardian, or delegating powers of attorney, is a statement that that you trust that person’s judgment to do what is best in various situations, including some of those outlined above. But I think it’s worthwhile to think through some of the softer, nonfinancial issues that could arise in your later years. Some of these issues, such as providing for the care of pets or getting specific about the disposition of your physical property, can be addressed with legally binding estate-planning documents. Other issues, such as how you’d like your loved ones to balance your care with their own quality of life, are best discussed with your loved ones and/or documented in writing on your own. (If you decide to leave physical or electronic documents that spell out your wishes on some of these matters, be sure to let your loved ones know how gain access to them.)

Attitudes Toward Guardianship

If you have minor children and have designated guardians to care for them if something should happen to you, you of course need to inform the guardians and make sure they’re OK with the responsibility. In addition, take the next step and communicate to your designated guardians about your priorities and values as a parent–your attitudes toward their education, spirituality, and financial matters, for example. And even if your children are grown–or getting there–it’s worthwhile to talk to close friends or family members about how you hope they’ll interact with your kids if you’re no longer around. After my sister lost a dear friend to cancer, for example, she and a group of other close friends serve as surrogate “moms” to their late friend’s daughter, now in her mid-20s. There’s no substitute for an actual mom, of course but it’s a relationship they all cherish, and they’re happy they discussed it with their friend before she passed away.

Attitudes Toward Life During Dementia

Given the increased incidence of dementia in the developed world, an outgrowth of longer life expectancies, it’s worth thinking through and communicating to your loved ones your attitudes toward your care and quality of life if you develop dementia. Would you prioritize in-home care above all else, or would care delivered in a facility be agreeable if it improved your spouse’s quality of life? Would you want your spouse or other loved ones to try to care for you themselves for as long as possible, or would you rather they delegated those responsibilities to paid caregivers, assuming the family finances could support it? How would you like your loved ones to balance your quality of life with their own? How would you like them to balance your health and safety with your own quality of life? How important would it be to you to receive daily visits from your spouse and other loved ones, even it meant that those obligations would detract from their ability to travel or pursue other activities? Would you prefer to keep your decline as private as possible, or would you rather be out in public interacting with people no matter what? There’s no “right” answer to any of these questions, but talking through them can help your loved ones be at peace with the decisions they could eventually make.

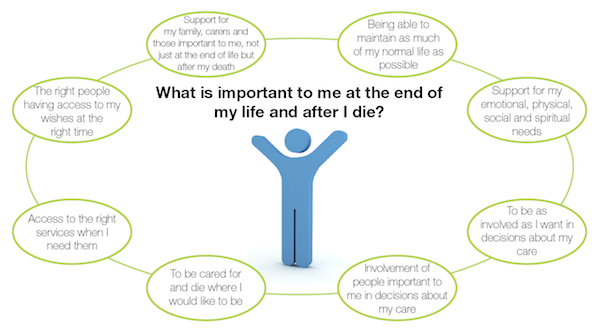

Attitudes Toward End-of-Life Care

I first became aware of The Conversation Project, designed by to help people discuss their own thoughts on end-of-life care, on NPR. In the segment, two adult daughters used “The Conversation” template to interview their elderly dad about the decisions they might eventually make on his behalf. Their father had drafted an advance directive that specified, rather strictly, that he didn’t want any life-sustaining care if he had no chance for a good quality of life. But one of the daughters asked whether it would be OK if they took a bit more time with the decision to let him go if it provided them with a sense of peace. Without skipping a beat, the dad said, “Oh, of course. Absolutely.” That conversation drove home the importance of adding nuance to the end-of-life discussion, above and beyond what could be provided by living wills or advance directives. You can read more about The Conversation Project and download a conversation starter kit here, but don’t feel bound by it. If there are important end-of-life issues that it doesn’t address, feel free to expand the discussion with your loved ones and/or commit them to writing.

Attitudes Toward Funerals, Burials, Etc.

Many people make plans for any funerals/memorials and the disposition of their bodies well in advance; the right approach to these issues may be predetermined by culture or religion. But for other people, attitudes toward these matters aren’t obvious at all, so it’s useful to spell out your wishes in advance, either verbally, in writing, or both. (My mother initially insisted that my dad would be buried rather than cremated, but even she was convinced that cremation was the right thing after we found three written statements from him about his desire to be cremated.) Maybe your wishes are simply to have your loved ones say goodbye in whatever way gives them the most peace at that time; in that case, tell them that or write that down.

Attitudes Toward Care of Pets

It’s a cliche to say that pets are like family members, but for many people, that’s absolutely the case. The good news is that you can actually lay the groundwork for continuing care for your pet as part of your estate plan. The gold standard, albeit one that entails costs to set up, is a pet trust; through such a trust, you detail which pets are covered, who you’d like to care for them and how, and leave an amount of money to cover the pet’s ongoing care. Alternatively, you can use a will to specify a caretaker for your pet and leave additional assets to that person to care for the pet; the downside of this arrangement is that the person who inherits those assets isn’t legally bound to use the money for the pet’s care. At a minimum, develop at least a verbally communicated plan for caretaking for your pet if you’re unable to do so–either on a short- or long-term basis. This fact sheet provides helpful tips to ensure for your pets’ continuous well-being.

Attitudes about Disposition of Personal Possessions

Are there specific physical assets you’d like to earmark for children, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, or friends? If so, your estate-planning attorney can help you codify the disposition of those assets in your will so there’s no confusion. Also let your loved ones know if there are physical assets that you’d like to stay within the family (again, your will is the best way to do this). Importantly, you should also let them know what you don’t feel strongly about them selling or otherwise disposing of when you’re gone. Do you want your executor to take pains to divide the assets equally among your heirs so that everyone receives tangible property of similar value? The topic of dividing up tangible property among family members is a complicated one, to put it mildly; the more you say about your wishes in advance, the better off everyone will be in the end.

Complete Article HERE!