By

[S]everal weeks after my patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for pneumonia and other problems, a clear plastic tube sprouted up from the mechanical ventilator, onto his pillow and down into his trachea. He showed few signs of improvement. In fact, the weeks on his back in an I.C.U. bed were making my 59-year-old patient more and more debilitated.

Still worse, a law meant to protect him was probably making him suffer more.

When the prognosis looks this bad, clinicians typically ask the patient what kind of care they want. Should we push for a miracle or focus on comfort? When patients cannot speak for themselves, we ask the same questions of a loved one or a legal guardian. This helps us avoid giving unwanted care that isn’t likely to heal the patient.

This patient was different. Because he was born with a severe intellectual disability, the law made it much harder for him to avoid unwanted care.

In New Hampshire, where I practice, and in many other states, legal guardians of people with intellectual disabilities can make most medical decisions but, by law, they cannot decline life-sustaining therapies like mechanical ventilation. These laws are meant to protect patients with disabilities from premature discontinuation of lifesaving care. Yet, my patient was experiencing the unintended downside of these laws: the selective prolonging of unpleasant and questionably helpful end-of-life care in people with disabilities.

For my patient’s guardian to discontinue unwanted life-sustaining therapies, she had to petition a probate court judge. Busy court dockets being what they are, this can take weeks. Once in court, the judge asks questions aimed at making the right legal decision. How sure is the guardian or family member of the patient’s wishes? What’s the doctor’s best estimate at a prognosis? Often the judge will ask an ethicist like me to weigh in on whether withdrawal is an ethically permissible option. Then the judge makes a decision.

This slow, impersonal, courtroom-based approach to end-of-life decision-making is a far cry from the prompt, patient-centered, bedside care that all of us deserve.

This legalistic approach to end-of-life decision-making also creates unreasonable expectations of legal guardians. Most loved ones have a sense of what the patient they represent would want at the end of life, but they would probably squirm to justify that intuition in a court of law. Yet this is routine for legal guardians of people with intellectual disabilities in my state and others with similar laws. This biases our care toward continuation of what are often uncomfortable, aggressive and potentially unwanted end-of-life treatments.

My patient’s legal guardian was not a family member, but she had known him for years before this hospitalization. She said my patient’s quality of life came from interacting non-verbally with caregivers, listening to music, and eating favorite foods like applesauce. She described the excited hoots he would make when interacting with a favorite nurse.

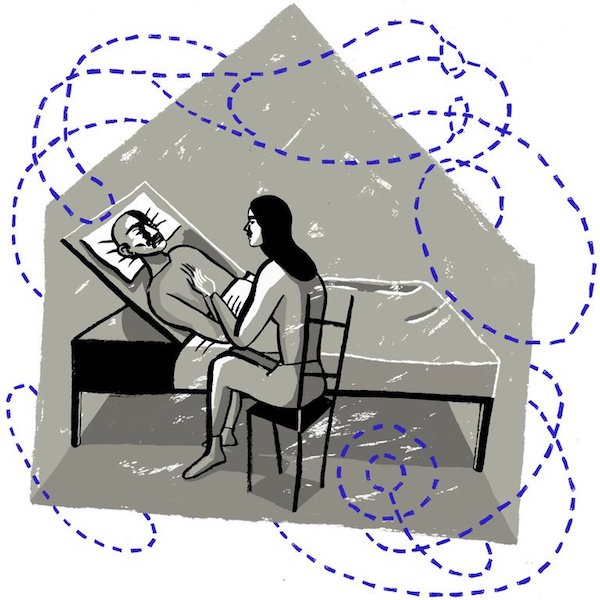

The contrast to what my patient was experiencing in the I.C.U. was stark. He was sedated. His unsmiling mouth drooped open, a breathing tube between his lips. In place of music, there were the beeps and whirs of the machines that kept him alive. He could not eat. Plastic tubes penetrated every orifice.

Still further, my patient endured the discomforts and indignities that accumulate even in the best I.C.U.s. His muscles grew weaker and stiffer. He developed skin sores and infections. He needed minor surgeries to place the tubes that delivered artificial nutrition and artificial breaths every hour of the day.

Seeing all of this, my patient’s guardian did not think my patient would want to live this way. The I.C.U. can save your life, but it is not where most of us want to die.

In other states, patients with intellectual disabilities have an equal right, via the advocacy of their legal guardians, to avoid unwanted care. A 2010 New York State law, for instance, lets the legal guardians of people with intellectual disabilities withdraw life-sustaining therapies as long as doing so fits the guardian’s sense of the patient’s wishes.

In accord, a policy statement from the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities states, “Withdrawing or withholding care may be appropriate in some situations …. Treatment should not be withdrawn or withheld only because a person has a disability.”

This reference to substandard medical treatment of people with disabilities is important. In hospitals across the country, people with disabilities have been subject to all manner of substandard care, including inappropriately premature discontinuation of end-of-life care. This has improved over the past few decades, but a new systematic review shows people with intellectual disabilities still have difficulty accessing high quality end-of-life care, including palliative care specialists. That means the medical system routinely shortchanges people with intellectual disabilities at the end of life, and states like mine add legal insult to that medical injury.

My patient’s caregivers held several multidisciplinary meetings to choose the right way forward. There was consensus that the medical prognosis was dim, and the legal guardian said the patient did not have adequate quality of life. Multiple physicians wrote letters to support a petition to the court to refocus care around comfort and dignity. Ultimately, the legal guardian and the Office of Public Guardian felt they could decline continued intensive care only if it was completely futile, and decided not to submit the petition to the court.

To date, my patient has spent over 140 days in the hospital with little overall improvement. He has endured multiple medical interventions, and unavoidable complications are mounting. Unless the laws change, I.C.U.s across the nation will continue to do the same thing to other patients just like him.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!