The Tragic History of How Pandemics Have Disrupted Mourning

On a recent Monday in a New Jersey cemetery, social worker Jane Blumenstein held a laptop with the screen facing a gravesite. A funeral was being held over Zoom, for a woman who died of COVID-19. It was a brilliantly sunny day, so a funeral worker held an umbrella over Blumenstein to shield the laptop from any glare, as synagogue members and family members of the deceased sang and said prayers.

The experience was a “surreal” one for Blumenstein, who is a synagogue liaison at Dorot, a social-services organization that works with the elderly in the New York City area. “I felt really privileged that I could be there and be the person who was allowing this to be transmitted.”

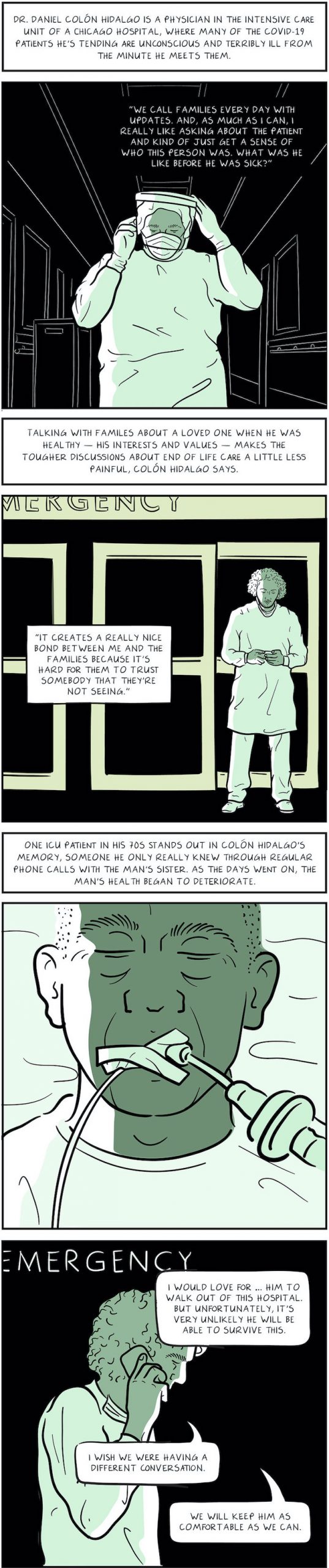

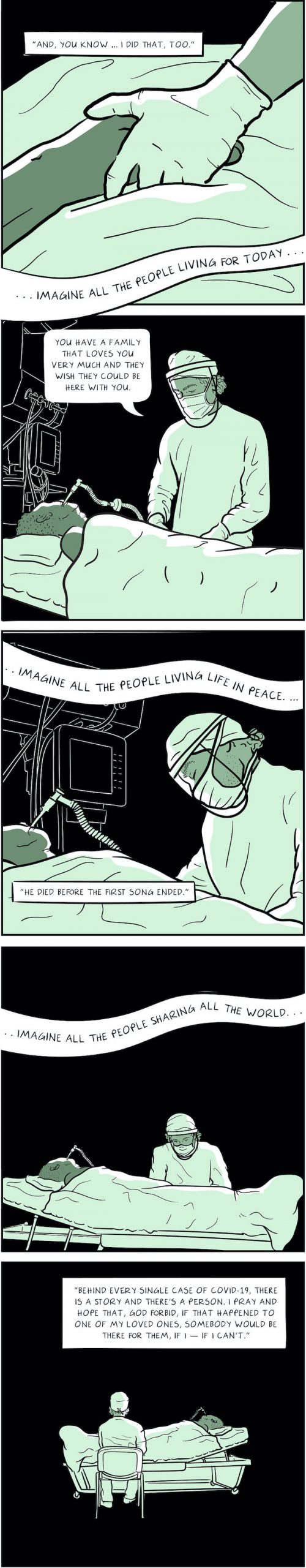

The roughly 20-minute ceremony was one of countless funerals that have taken place over Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic. As authorities limit the size of gatherings — and hospitals limit visitors in order to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus — loved ones have been unable to gather for traditional mourning rituals in the aftermath of a death, so it has become the norm for those who die to do so without their families by their sides, able to say goodbye only virtually, if at all.

The rising death toll has overwhelmed funeral homes and cemeteries, further limiting what is possible. Across religions and around the world, end-of-life traditions have been rendered impossible: stay-at-home orders have stopped Jewish people from sitting shiva together; overwhelmed funeral services have meant Islam’s ritual washing of the body has been skipped; Catholic priests may have had to settle for drive-through funerals, in which the coffin is blessed in front of just a few immediate family members.

The effects of COVID-19 will be felt for many years to come, but those who have lost loved ones are feeling those effects immediately — and, for many, their pain has been exacerbated by the inability to say goodbye. The horror of these rushed goodbyes may be looked back on as a defining feature of the COVID-19 pandemic. But, as the tragic history of pandemics reveals, it is something that disease has forced human beings to struggle with throughout history.

For example, during a 1713 plague epidemic in Prague, a shortage of burial supplies heightened the pain of rushed burials. The emotional toll is evident in a Yiddish poem written shortly after the outbreak, translated for TIME by Joshua Teplitsky, professor of History at Stony Brook University, who is writing a book about this period. At the sight of the dead being carried away day and night, “all weep and wail!,” the poem says. “Who ever heard of such a thing in all his life?” The poem describes people working around the clock and through the Sabbath to saw planks for coffins and sew shrouds.

In one 1719 book, a rabbi recalls counseling a man who was anxious about burying his plague-stricken father in the local cemetery because of a government requirement to coat the body in a chemical to accelerate decomposition. He asked the rabbi if it would be more respectful to bury his father in a forest far outside of the city. The rabbi told the man to follow the rules, likely thinking that “if the body gets buried in the woods, in a very short time, it will be lost, and if it’s in the cemetery, the rabbi is expecting that when this plague passes, visitors will go pray and pay their respects,” says Teplitsky.

Indeed, Teplitsky found a prayer printed circa 1718-1719 that he believes women may have recited while walking around a cemetery years after the epidemic, asking the dead for forgiveness for the lack of a traditional funeral and burial five years earlier.

Centuries later, during the 1918-1919 flu pandemic, Italians were likewise thrust into a world in which funerals had to take place quickly, without ceremonies or religious rites. According to research by Eugenia Tognotti, an expert in public health and quarantine, and a professor of history of medicine and human sciences at the University of Sassari, Italy, many expressed horror at hurried burials in letters to friends and relatives, which are preserved at the Central State Archive in Rome. “The more common lamentations are: ‘Not priests, nor crosses, nor bells’ and ‘one dies like an animal without the consolation of family and friends,’” Tognotti told TIME. Another woman wrote to a relative in Topsfield, Mass., “Here [in Italy] there is a mortal disease named Spanish flu: the sick die in four or more days, a bucket of lime is thrown over the dead bodies, and then four workers take them to the graves like dogs.”

The horror was similar in the U.S., especially in Philadelphia, an epicenter of the pandemic. Columba Voltz was an 8-year-old daughter of a tailor back then, who said that funeral bells tolled all day long as coffins were carried into a local church for a quick blessing and then carried out a few minutes later, according to Catharine Arnold’s Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History. “I was very scared and depressed. I thought the world was coming to an end,” Voltz recounted.

Inside one such house, Anna Milani’s parents laid her 2-year-old brother Harry to rest with what they had on hand:

There were no embalmers, so my parents covered Harry with ice. There were no coffins, just boxes painted white. My parents put Harry in a box. My mother wanted him dressed in white — it had to be white. So she dressed him in a little white suit and put him in the box. You’d think he was sleeping. We all said a little prayer. The priest came over and blessed him. I remember my mother putting in a white piece of cloth over his face; then they closed the box. They put Harry in a little wagon, drawn by a horse. Only my father and uncle were allowed to go to the cemetery. When they got there, two soldiers lowered Harry into a hole.

The same concerns that would have limited attendance at the cemetery when Harry Milani was buried reared their heads more recently during the 2014-2016 epidemic of Ebola, a disease that can be spread through contact with the remains of those it kills. More than 300 cases came from one Sierra Leone funeral, and 60% of Guinea cases came from burial practices, according to the World Health Organization. In Liberia, mass cremations ran counter to traditional burial practices that include close contact with bodies. In Sierra Leone, the dead were put in body bags, sprayed with chlorine and buried in a separate cemetery designated for these victims. As traditional burial practices were curbed in an attempt to stop the spread, the dismay caused by this situation, Tognotti notes, was the same feeling experienced by those Italians of the early 20th century who wrote of the pain of the flu pandemic.

Sometimes, however, victims of epidemics who knew the end was near were actually hoping for a departure from the usual norms of burial and mourning: they wanted their deaths to be used to remind authorities to take these crises seriously.

This idea of the political funeral is particularly associated with the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s. The activist group ACT UP spread the ashes of victims over the White House lawn, and staged political funerals—open-casket processions, such as the one that brought Mark Lowe Fisher’s body to the Republican National Committee’s NYC headquarters ahead of the 1992 presidential election. “I have decided that when I die I want my fellow AIDS activists to execute my wishes for my political funeral,” Fisher wrote, in a statement entitled Bury Me Furiously. “We are not just spiraling statistics; we are people who have lives, who have purpose, who have lovers, friends and families. And we are dying of a disease maintained by a degree of criminal neglect so enormous that it amounts to genocide.”

The inability to give loved ones proper send-offs is often a hidden cost of these pandemics, Tognotti says, and should not be ignored by officials. Even with modern knowledge about disease transmission, awareness of the reasons for public-health guidance doesn’t lessen the desire to participate in rituals. “The emotional strain of not being able to dispose of the dead promptly, and in accordance with cultural and religious customs, has the power to create social distress and unrest and needs to be considered in contemporary pandemic preparedness planning,” she says.

In this pandemic, a new openness about talking about mental health issues could help. For example, New York state launched a hotline so residents can talk to a therapist for free, and some sites host virtual sessions to discuss grief. Mourners can opt for live-streaming and video conferencing and include more people virtually than before.

For others, these virtual gatherings and brief blessings at the cemetery are placeholders. In March, after Alfredo Visioli, 83, was buried in a cemetery near Cremona in northern Italy, with no relatives allowed to attend and a brief blessing from a priest, his grand-daughter Marta Manfredi told Reuters that, “When all this is over, we will give him a real funeral.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!