Life is a bitch. Then you die. So while staring at my navel the other day, I decided that that bitch happens in four stages. Here they are.

Stage One: Mimicry

We are born helpless. We can’t walk, can’t talk, can’t feed ourselves, can’t even do our own damn taxes.

As children, the way we’re wired to learn is by watching and mimicking others. First we learn to do physical skills like walk and talk. Then we develop social skills by watching and mimicking our peers around us. Then, finally, in late childhood, we learn to adapt to our culture by observing the rules and norms around us and trying to behave in such a way that is generally considered acceptable by society.

The goal of Stage One is to teach us how to function within society so that we can be autonomous, self-sufficient adults. The idea is that the adults in the community around us help us to reach this point through supporting our ability to make decisions and take action ourselves.

But some adults and community members around us suck.1 They punish us for our independence. They don’t support our decisions. And therefore we don’t develop autonomy. We get stuck in Stage One, endlessly mimicking those around us, endlessly attempting to please all so that we might not be judged.2

In a “normal” healthy individual, Stage One will last until late adolescence and early adulthood.3 For some people, it may last further into adulthood. A select few wake up one day at age 45 realizing they’ve never actually lived for themselves and wonder where the hell the years went.

This is Stage One. The mimicry. The constant search for approval and validation. The absence of independent thought and personal values.

We must be aware of the standards and expectations of those around us. But we must also become strong enough to act in spite of those standards and expectations when we feel it is necessary. We must develop the ability to act by ourselves and for ourselves.

Stage Two: Self-Discovery

In Stage One, we learn to fit in with the people and culture around us. Stage Two is about learning what makes us different from the people and culture around us. Stage Two requires us to begin making decisions for ourselves, to test ourselves, and to understand ourselves and what makes us unique.

Stage Two involves a lot of trial-and-error and experimentation. We experiment with living in new places, hanging out with new people, imbibing new substances, and playing with new people’s orifices.

In my Stage Two, I ran off and visited fifty-something countries. My brother’s Stage Two was diving headfirst into the political system in Washington DC. Everyone’s Stage Two is slightly different because every one of us is slightly different.

Stage Two is a process of self-discovery. We try things. Some of them go well. Some of them don’t. The goal is to stick with the ones that go well and move on.

Stage Two is a process of self-discovery. We try things. Some of them go well. Some of them don’t. The goal is to stick with the ones that go well and move on.

Stage Two lasts until we begin to run up against our own limitations. This doesn’t sit well with many people. But despite what Oprah and Deepak Chopra may tell you, discovering your own limitations is a good and healthy thing.

You’re just going to be bad at some things, no matter how hard you try. And you need to know what they are. I am not genetically inclined to ever excel at anything athletic whatsoever. It sucked for me to learn that, but I did. I’m also about as capable of feeding myself as an infant drooling applesauce all over the floor. That was important to find out as well. We all must learn what we suck at. And the earlier in our life that we learn it, the better.

So we’re just bad at some things. Then there are other things that are great for a while, but begin to have diminishing returns after a few years. Traveling the world is one example. Sexing a ton of people is another. Drinking on a Tuesday night is a third. There are many more. Trust me.

Your limitations are important because you must eventually come to the realization that your time on this planet is limited and you should therefore spend it on things that matter most. That means realizing that just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should do it. That means realizing that just because you like certain people doesn’t mean you should be with them. That means realizing that there are opportunity costs to everything and that you can’t have it all.

There are some people who never allow themselves to feel limitations — either because they refuse to admit their failures, or because they delude themselves into believing that their limitations don’t exist. These people get stuck in Stage Two.

These are the “serial entrepreneurs” who are 38 and living with mom and still haven’t made any money after 15 years of trying. These are the “aspiring actors” who are still waiting tables and haven’t done an audition in two years. These are the people who can’t settle into a long-term relationship because they always have a gnawing feeling that there’s someone better around the corner. These are the people who brush all of their failings aside as “releasing” negativity into the universe or “purging” their baggage from their lives.

At some point we all must admit the inevitable: life is short, not all of our dreams can come true, so we should carefully pick and choose what we have the best shot at and commit to it.

But people stuck in Stage Two spend most of their time convincing themselves of the opposite. That they are limitless. That they can overcome all. That their life is that of non-stop growth and ascendance in the world, while everyone else can clearly see that they are merely running in place.

In healthy individuals, Stage Two begins in mid- to late-adolescence and lasts into a person’s mid-20s to mid-30s.4 People who stay in Stage Two beyond that are popularly referred to as those with “Peter Pan Syndrome” — the eternal adolescents, always discovering themselves, but finding nothing.

Stage Three: Commitment

Once you’ve pushed your own boundaries and either found your limitations (i.e., athletics, the culinary arts) or found the diminishing returns of certain activities (i.e., partying, video games, masturbation) then you are left with what’s both a) actually important to you, and b) what you’re not terrible at. Now it’s time to make your dent in the world.

Stage Three is the great consolidation of one’s life. Out go the friends who are draining you and holding you back. Out go the activities and hobbies that are a mindless waste of time. Out go the old dreams that are clearly not coming true anytime soon.

Then you double down on what you’re best at and what is best to you. You double down on the most important relationships in your life. You double down on a single mission in life, whether that’s to work on the world’s energy crisis or to be a bitching digital artist or to become an expert in brains or have a bunch of snotty, drooling children. Whatever it is, Stage Three is when you get it done.

Stage Three is all about maximizing your own potential in this life. It’s all about building your legacy. What will you leave behind when you’re gone? What will people remember you by? Whether that’s a breakthrough study or an amazing new product or an adoring family, Stage Three is about leaving the world a little bit different than the way you found it.

Stage Three ends when a combination of two things happen: 1) you feel as though there’s not much else you are able to accomplish, and 2) you get old and tired and find that you would rather sip martinis and do crossword puzzles all day.

In “normal” individuals, Stage Three generally lasts from around 30-ish-years-old until one reaches retirement age.

People who get lodged in Stage Three often do so because they don’t know how to let go of their ambition and constant desire for more. This inability to let go of the power and influence they crave counteracts the natural calming effects of time and they will often remain driven and hungry well into their 70s and 80s.5

Stage Four: Legacy

People arrive into Stage Four having spent somewhere around half a century investing themselves in what they believed was meaningful and important. They did great things, worked hard, earned everything they have, maybe started a family or a charity or a political or cultural revolution or two, and now they’re done. They’ve reached the age where their energy and circumstances no longer allow them to pursue their purpose any further.

The goal of Stage Four then becomes not to create a legacy as much as simply making sure that legacy lasts beyond one’s death.

This could be something as simple as supporting and advising their (now grown) children and living vicariously through them. It could mean passing on their projects and work to a protégé or apprentice. It could also mean becoming more politically active to maintain their values in a society that they no longer recognize.

Stage Four is important psychologically because it makes the ever-growing reality of one’s own mortality more bearable. As humans, we have a deep need to feel as though our lives mean something. This meaning we constantly search for is literally our only psychological defense against the incomprehensibility of this life and the inevitability of our own death.6 To lose that meaning, or to watch it slip away, or to slowly feel as though the world has left you behind, is to stare oblivion in the face and let it consume you willingly.

What’s the Point?

Developing through each subsequent stage of life grants us greater control over our happiness and well-being.7

In Stage One, a person is wholly dependent on other people’s actions and approval to be happy. This is a horrible strategy because other people are unpredictable and unreliable.

In Stage Two, one becomes reliant on oneself, but they’re still reliant on external success to be happy — making money, accolades, victory, conquests, etc. These are more controllable than other people, but they are still mostly unpredictable in the long-run.

Stage Three relies on a handful of relationships and endeavors that proved themselves resilient and worthwhile through Stage Two. These are more reliable. And finally, Stage Four requires we only hold on to what we’ve already accomplished as long as possible.

At each subsequent stage, happiness becomes based more on internal, controllable values and less on the externalities of the ever-changing outside world.

Inter-Stage Conflict

Later stages don’t replace previous stages. They transcend them. Stage Two people still care about social approval. They just care about something more than social approval. Stage 3

people still care about testing their limits. They just care more about the commitments they’ve made.

Each stage represents a reshuffling of one’s life priorities. It’s for this reason that when one transitions from one stage to another, one will often experience a fallout in one’s friendships and relationships. If you were Stage Two and all of your friends were Stage Two, and suddenly you settle down, commit and get to work on Stage Three, yet your friends are still Stage Two, there will be a fundamental disconnect between your values and theirs that will be difficult to overcome.

Generally speaking, people project their own stage onto everyone else around them. People at Stage One will judge others by their ability to achieve social approval. People at Stage Two will judge others by their ability to push their own boundaries and try new things. People at Stage Three will judge others based on their commitments and what they’re able to achieve. People at Stage Four judge others based on what they stand for and what they’ve chosen to live for.

The Value of Trauma

Self-development is often portrayed as a rosy, flowery progression from dumbass to enlightenment that involves a lot of joy, prancing in fields of daisies, and high-fiving two thousand people at a seminar you paid way too much to be at.

But the truth is that transitions between the life stages are usually triggered by trauma or an extreme negative event in one’s life. A near-death experience. A divorce. A failed friendship or a death of a loved one.

Trauma causes us to step back and re-evaluate our deepest motivations and decisions. It allows us to reflect on whether our strategies to pursue happiness are actually working well or not.

What Gets Us Stuck

The same thing gets us stuck at every stage: a sense of personal inadequacy.

People get stuck at Stage One because they always feel as though they are somehow flawed and different from others, so they put all of their effort into conforming into what those around them would like to see. No matter how much they do, they feel as though it is never enough.

Stage Two people get stuck because they feel as though they should always be doing more, doing something better, doing something new and exciting, improving at something. But no matter how much they do, they feel as though it is never enough.

Stage Three people get stuck because they feel as though they have not generated enough meaningful influence in the world, that they make a greater impact in the specific areas that they have committed themselves to. But no matter how much they do, they feel as though it is never enough.8

One could even argue that Stage Four people feel stuck because they feel insecure that their legacy will not last or make any significant impact on the future generations. They cling to it and hold onto it and promote it with every last gasping breath. But they never feel as though it is enough.

The solution at each stage is then backwards. To move beyond Stage One, you must accept that you will never be enough for everybody all the time, and therefore you must make decisions for yourself.

To move beyond Stage Two, you must accept that you will never be capable of accomplishing everything you can dream and desire, and therefore you must zero in on what matters most and commit to it.

To move beyond Stage Three, you must realize that time and energy are limited, and therefore you must refocus your attention to helping others take over the meaningful projects you began.

To move beyond Stage Four, you must realize that change is inevitable, and that the influence of one person, no matter how great, no matter how powerful, no matter how meaningful, will eventually dissipate too.

And life will go on.

Footnotes

- Often this occurs because the adults/community themselves are still stuck in Stage One.↵

- Some people who get stuck in Stage One get stuck because they come to believe that they will never be able to fit in. These people usually succumb to some form of distraction, depression or addiction.↵

- I put normal in quotes because, really, what the fuck is normal?↵

- Stages can overlap to a certain extent. Transitioning between them is never black/white. It happens gradually. And often with some emotional stress and major lifestyle changes.↵

- This applies to the rare individuals who are talented and capable enough to still remain highly influential and relevant into their 70s and 80s as well. Stage Three doesn’t end until the desire for some peace and quiet outweighs one’s ability to affect change in the world. Some people die without ever leaving Stage Three.↵

- For more on this, see The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker.↵

- Research shows that generally people become happier and more satisfied as their lives go on.↵

- One way to think about it is that people who are stuck at Stage Two always feel as though they need more breadth of experience, whereas Stage Three people get stuck because they always feel as though they need more depth.↵

Complete Article HERE!

For Jewish Students, Field Trip Is Window on Death and Dying

Two yellow buses pulled away from Yeshiva High School here with a couple of class periods still left and the 77 seniors aboard giddy with the words “field trip.” They texted. They posed for selfies. They sent up clouds of chatter about weekend plans.

Then, less than a half-hour later, they walked into a cool, tiled room at the Gutterman Warheit Memorial Chapel and stared at the pine coffins and the inclined metal table used for cleaning a corpse.

“I thought I was cool about death,” one girl whispered to a classmate. “But this ——”

“This” meant more than the contents of the room, which is used at the Jewish funeral home for the body-washing ritual called tahara. It connoted the entire mini-course that she, along with the rest of Yeshiva High School’s graduating class, is taking about the Judaic practices and traditions surrounding death, dying and grief.

Few subjects run more powerfully counter to an American teenager’s innate sense of immortality than a confrontation with the reality of life’s end. The study of death became more common at the college level with the publication of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s influential book, “On Death and Dying,” in 1969. But it is rare that the subject is discussed at the high school level, particularly with an approach that includes fairly explicit instruction in caring for a cadaver.

“As a senior, you’re thinking about going to college, and as a teenager you have this feeling of invincibility,” Daniel Feldan, 17, said the morning after the visit to the funeral home on Tuesday. “I’ve never had that other feeling — of mortality, that life might end soon.”

Bailey Frohlich, also 17, nodded at hearing her classmate’s words. “It’s given us a reality check,” she said. “For us, it’s usually about college and friends and extracurriculars. You don’t focus on the grittier things. But even if you don’t have a personal connection to death, thank God, it affects the whole community.”

The 10-hour, eight-session course, titled “The Final Journey: How JudaismDignifies the Final Passage,” aims for sensitivity even as it provokes a certain degree of shock. Besides going to the funeral home, where they received detailed explanations of washing and dressing a corpse, the students have classroom lessons on topics including the history of the Jewish burial societies known as chevra kadisha, the Talmudic foundations of end-of-life practices, and issues involving autopsy and organ donation.

“When we started the program, there was a lot of hesitation and curiosity at the same time,” said Rabbi Jonathan Kroll, 45, the yeshiva’s head of school. “Jewish tradition for dealing with burial and the process of tahara is not that well known. Even for a lot of well-educated Jews, the chevra kadisha is like a secret society. But once you start talking about the values involved or the practical aspects, there’s a fascination.”

The program at Yeshiva High School began with Rochel U. Berman, a 79-year-old author and a former nursing home worker who moved near the school 13 years ago. Her well-regarded book on Jewish burial rituals, “Dignity Beyond Death,” was published in 2005. Over the years she lived in South Florida and the New York metropolitan area, and she served as a chevra kadisha volunteer in both places, preparing the bodies of about 1,000 women and girls, from centenarians who simply wore out to an 18-month-old baby felled by cancer.

In broad ways, Jewish rituals around death and dying trace back to antiquity, and they have been central to Jewish continuity in the diaspora. The system of chevra kadisha emerged in Central Europe in the 16th century. Initially almost a social institution composed of the elite, chevra kadisha groups transformed over the centuries into an example of communal or congregational voluntarism.

An unlikely adopter of religious tradition, Ms. Berman grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba, as the child of secular socialists. Her Jewish language, rather than the Hebrew of worship and Zionism, was the Yiddish of the Old World shtetl and the New World slum.

By the time Ms. Berman’s father died in 1985, she had grown observant. Even so, between the final kiss she planted on his forehead in his deathbed and the lowering of the coffin into the ground the next day, she had no idea what had been done with her father’s body.

“I didn’t know what I was missing, but I knew there was a hole there,” she recalled. “And the not-knowing made me even sadder.”

While living in New York, she and her husband, George Berman, both started volunteering in their Orthodox synagogue’s chevra kadisha, which has separate units for each gender. The processes of washing and purifying the body, of dressing it in a white linen shroud, of moving it into a plain wooden coffin filled her with a sense of communal purpose.

Not content with her own years as a volunteer or with her book, Ms. Berman resolved to reach young people as a way of imbuing the next generation with those Judaic values. “It’s a gift to give them, a part of the Jewish life cycle they didn’t know about,” she said. “And once they know it, they’ll be the ambassadors in sharing it.”

Rabbi Kroll assumed the leadership of Yeshiva High School in Boca Raton, Fla., three years ago. Coincidentally, it turned out that he, somewhat later than Ms. Berman, had belonged to the same synagogue and volunteered in the same chevra kadisha in New York’s Westchester County.

With $21,000 in grants from foundations and religious organizations, Ms. Berman devised a curriculum. Rabbi Kroll tested it last year with half of the seniors in the class of 2015.

“We had pushback,” he recalled, “but it wasn’t serious pushback. Several parents questioned the priority: ‘Why not use the time on something more pertinent, more relevant?’ My impression is that the pushback was about their own discomfort with mortality.”

As for the first batch of students, half of them reported on evaluation forms that, as a result of the course, they would consider being in a chevra kadisha. That response was more than sufficient for Rabbi Kroll to expand the program to this year’s entire senior class. Among the 78 students, he said, only three have had an immediate family member die. (One of those three was excused from the funeral home trip.)

Even those like Maya Borzak, 18, whose grandfather served in a chevra kadisha, found there was plenty to learn. In fact, the funeral home visit occurred just five days before the unveiling of that grandfather’s headstone, which in Jewish tradition takes place after a year of mourning.

“I always knew that, in general, it’s important to have a Jewish identity, that you’re born a Jew and you need to die a Jew,” Maya said. “You have a circumcision if you’re a boy, you have baby-naming if you’re a girl, and then, at the end, everyone is buried in the same way.”

“Now I know more than the sources for the processes and rituals,” she said. “I know the dignity that is supposed to be provided for everyone who dies. It’s the great equalizer. We’re all in this together.”

Complete Article HERE!

Inter-Mission: Life between cancer remissions

by Janet Gildea

Most cancer survivors will admit that they never quite stop looking over their shoulders to see if a recurrence is creeping up on them. Having been caught by surprise once, nobody wants to be blind-sided again. My initial experience of ovarian cancer came in February 2008 when I was 52 years old, a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati practicing family medicine at the U.S.-Mexico border near El Paso, Texas.

I finished a course of radiation in November, and I heard the glorious words, “Your PET scan is totally clear!” I heaved a sigh of relief and spent the month of April at the New Jersey shore to cap off my recuperation and to see if I could begin to write a book about my journey with cancer, its recurrence and the transition to back to a new normal again. The project flowed well and I returned home to the border determined to continue writing on a regular schedule. But as I picked up my other ministry commitments and life resumed its usual pace, the document lay dormant.

I have had four months to come to terms with the probability of entering into a time of chemotherapy. It feels very different than the shock of my initial diagnosis in 2008, an experience than Jean Shinoda Bolen has described in Close to the Bone: Life Threatening Illness as a Soul Journey as “a personal earthquake.” My sensors not only detected what was coming, but I also knew how to use the waiting to prepare myself for the shocks ahead. From very practical details, such as knowing when to expect the loss of my hair and what type of liquids I find most palatable, to how to gather my spiritual and emotional resources, I have been able to get ready for this experience.

Visualization has been one of the helpful tools both to prepare me for treatment and to sustain me in its aftermath. In prayer I call on five spiritual “mothers,” three from my Sister of Charity tradition, as well as my own mother and Our Lady of Guadalupe. I have invited these dear women into my presence while lying under a radiation beam, trusting their hands to direct the energy exactly where it was needed and to protect my vital tissues from harm. During infusions of chemotherapy I give each of them an area of responsibility, and I find great comfort in their presence. Although I just happened upon this practice, a spiritual director suggested that it is perhaps a form of kything, a tradition that has been around for a very long time. What I know is that it brings me a sense of inner companionship during moments that are particularly lonely.

I have had time to consider what I will be able to do during chemo and what I will need to let go or put on hold. I cleared my calendar as much as possible for the next four months. I talked with my community and close friends to help me make some of the difficult decisions about where and how to use my energy. I spent time upfront establishing balance in my life rather than frantically trying to do as much as possible up to the moment I started chemo. This meant asking others to take on some of my responsibilities — and not feeling guilty about it. I had a great confirmation of this decision when I turned my wall calendar over to October and read, “Accept the gift you have given to so many people. Let people love you back.” Excellent advice, especially during this time, thanks to Jeanette Osias.

With whatever time I had left, I felt a call to serve in a capacity directed towards future generations in the church and in our congregation. Interestingly to me, as I lost all my generative organs I felt a surge of generativity, as though a creative energy was unblocked within me. A sense of urgency gave me the courage to imagine something new: a part-time diocesan ministry with young adults, while I resumed my congregational position as coordinator of vocation ministry and served with my sisters at Proyecto Santo Niño, a day program for children with special needs in Anapra, Mexico. As I finished chemotherapy and began the transition to survivorship, I felt that I had been “re-missioned.”

What will this new course of treatment hold for me? Having experienced six years with NED (cancer lingo for “no evidence of disease”), I can hope for that again. The possibility alone gives me a different perspective as I begin chemotherapy. Instead of dropping everything as I did during treatment the last time, I feel that I will be able to continue some home-based ministries that feed my soul. One of those is directing the pre-novitiate program for three women discerning with our congregation. The experience of intentional community living is a key part of the initial formation process. Living together in community in New Mexico during the next year we desire to create an environment where all of us can listen with our hearts to discern the “what’s next” of our lives. My experience of cancer treatment will be part of the mix as we learn to be sister to each other, sharing prayer and shouldering the chores and challenges of daily life and ministry.

An additional learning from last time around is that writing helps me make meaning of the experience of illness. This is what I hope to do as I write my way through the healing process over the next months in Global Sisters Report. I believe that this is a time of “inter-mission,” to live my call between remission and remission, when I have much to learn, to discern and to discover as I open myself to God’s healing ways.

Complete Article HERE!

A Racial Gap In Attitudes Toward Hospice Care

By Sarah Varney

BUFFALO — Twice already Narseary and Vernal Harris have watched a son die. The first time — Paul, at age 26 — was agonizing and frenzied, his body tethered to a machine meant to keep him alive as his incurable sickle cell disease progressed. When the same illness ravaged Solomon, at age 33, the Harrises reluctantly turned to hospice in the hope that his last days might somehow be less harrowing than his brother’s.

Their expectations were low. “They take your money,” Mrs. Harris said, describing what she had heard of hospice. “Your loved ones don’t see you anymore. You just go there and die.”

Hospice use has been growing fast in the United States as more people choose to avoid futile, often painful medical treatments in favor of palliative care and dying at home surrounded by loved ones. But the Harrises, who are African-American, belong to a demographic group that has long resisted the concept and whose suspicions remain deep-seated.

It is an attitude borne out by recent federal statistics showing that nearly half of white Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in hospice before death, compared with only a third of black patients. The racial divide is even more pronounced when it comes to advance care directives — legal documents meant to help families make life-or-death decisions that reflect a patient’s choices. Some 40 percent of whites aged 70 and over have such plans, compared with only 16 percent of blacks.

Instead, black Americans — far more so than whites — choose aggressive life-sustaining interventions, including resuscitation and mechanical ventilation, even when there is little chance of survival.

The racial gaps could widen when Medicare is expected to begin paying physicians in January 2016 for end-of-life counseling, and at a time when blacks and other minorities are projected to make up 42 percent of people 65 and over in 2050, up from 20 percent in 2000.

At the root of the resistance, say researchers and black physicians, is a toxic distrust of a health care system that once displayed “No Negroes” signs at hospitals, performed involuntary sterilizations on black women and, in an infamous Tuskegee study, purposely left hundreds of black men untreated for syphilis.

“You have people who’ve had a difficult time getting access to care throughout their lifetimes” because of poverty, lack of health insurance or difficulty finding a medical provider, said Dr. Maisha Robinson, a neurologist and palliative medicine physician at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. “And then you have a physician who’s saying, ‘I think that we need to transition your mother, father, grandmother to comfort care or palliative care.’ People are skeptical of that.”

Federal policies surrounding hospice also arouse suspicion in black communities since Medicare currently requires patients to give up life-sustaining therapies in order to receive hospice benefits.

That trade-off strikes some black families, who believe they have long had to fight for quality medical care, as unfair, said Dr. Kimberly Johnson, a Duke University associate professor of medicine who has studied African-American attitudes about hospice.

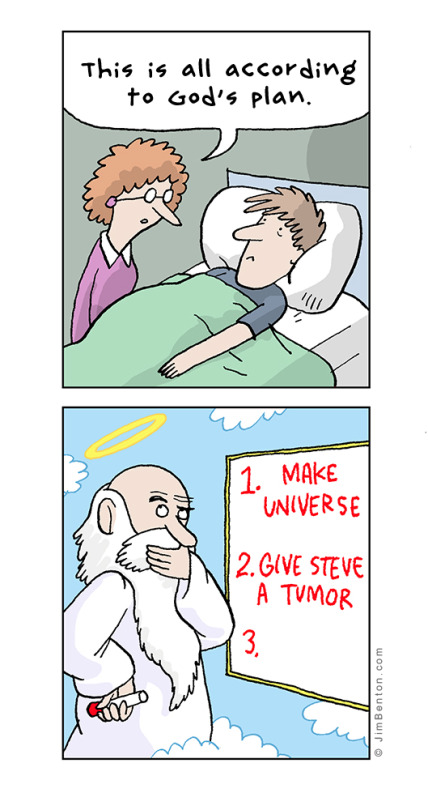

Dr. Johnson said her black patients were more likely to believe there are actual religious prohibitions against limiting life-sustaining therapy, and that suffering can be redemptive, or “a test from God.” And those beliefs, she added, were “contrary to the hospice philosophy of care.”

But now some doctors and clergy members are trying to use church settings to reshape the black community’s views, incorporating the topic in sermons, Bible study groups and grief and bereavement ministries.

Dr. Robinson, who is black and a daughter of Tennessee pastors, has been helping pastors develop faith-based hospice guidelines. She tells them, “God can work miracles, yes he can, but even in hospice.”

That message recently rang out from the pulpit at God Answers Prayer Ministries, an African- American church in South Los Angeles, as Bishop Gwendolyn Coates-Stone tried a sermon theme on advance care.

“It’s such a great cost to hold on to some of those sicknesses and diseases that eventually are going to take us out,” she exclaimed into a microphone, bobbing and weaving in a swirl of royal purple robes. “Just like Jesus talked about his death and prepared his disciples for his death, we ought to be preparing our disciples for our death!”

In a moment of benediction, Bishop Coates-Stone made a direct plea: “Help us Lord to have the courage to have conversations with our families,” she said, “that will also not leave them wandering and wondering, ‘What should I do in case of the death of a loved one?’”

A gathering of older blacks convened recently by Dr. Robinson in Leimert Park, a middle-class Los Angeles neighborhood, underscored the challenges such efforts still face.

“Hospice has not been a good place for African-Americans, unless you’re in a white facility and usually you’re one of few black people there,” said one woman, who along with others attending the gathering asked not to be identified in order to speak frankly.

That sentiment was greeted by nods from others in the group. “It gets into money,” another woman said. “The treatment is a little bit better, but then there is still the discrimination.”

Advance directives, in particular, are often seen as sinister, a way for insurance companies to maximize profits. “If you say you want at all costs to live, and they say, ‘Well, your insurance company doesn’t allow that,’ then they’re going to pull the plug anyway,” said the host of the gathering, Loretta Jones, 73, founder of Healthy African-American Families in Los Angeles.

To help allay those concerns, physicians need to be more explicit during end-of-life discussions, Dr. Robinson said. “We have to be much clearer about why we’re trying to have those conversations, or we’ll continue to see a pattern of people who really want life-sustaining interventions even when there’s limited potential benefit.”

Camille Wicher, vice president of clinical operations at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, who has studied African-Americans’ end-of-life choices, said hospitals needed to enlist black families who have had good hospice experiences to share their stories with friends and church members.

“That’s how we learn,” she added. “We learn from each other.”

The Harrises are trying to use their experience to carry out that work.

The agony of their son Paul’s death in a hospital room informed their treatment decisions when their next son, Solomon, became gravely ill. When his doctor conceded that blood transfusions were of little help, Solomon assented to hospice care in his parents’ home. If he was going to be robbed of his future, Solomon would not, his parents decided, be robbed of a good death.

All the while, parishioners from his parents’ church visited Solomon, amazed to find that hospice was not the grim banishment they had always envisioned.

“One of the members said, ‘I thought you were going to put Solomon in hospice,’ ” Mrs. Harris recalled. “I said, ‘We did.’ ‘Well, when is he going?’ I said, ‘They come here.’ ‘They come to your house?’ ‘Yeah, they’re taking care of him right here.’ ”

There was even time for reflection, as Solomon wrote in a poem called “After Life.”

“Fear death?” he wrote. “No, I await death.”

Solomon died a short while later, but the Harrises say his death has had a lasting impact.

“The people in our immediate circle now view hospice positively,” Mrs. Harris said. “I think our experience was powerful enough that it changed people’s attitudes.”

Mr. Harris, the pastor of Prince of Peace Temple Church of God in Christ, often evangelizes about hospice during his Sunday morning sermons, while Mrs. Harris has enlisted the wives of black pastors in Western New York, known as the “First Ladies,” to counter negative views about palliative care. At a recent meeting, the women discussed older church members who might benefit from hospice, and Mrs. Harris wanted to hear how parishioners in the women’s churches responded to some recent outreach.

“It really opened up people’s eyes to the negative stigma of it, feeling like, ‘I’m just putting my loved one away, and not caring for them,’ ” said Joyce Badger of Bethesda World Harvest International Church in Buffalo. “The power of knowledge that we’ve gained is really going to help our community.”

Complete Article HERE!

When I die

In this intimate portrait, Philip Gould wrestles with the meaning, and unexpected ecstasy, of impending death

Philip Gould was diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus in 2008, and in the summer of 2011 he was given three months to live. Filmed during the last two weeks of his life, this intimate portrait reveals Gould’s quest to find meaning in what he called ‘the death zone’.

Gould believed that for the terminally ill and those close to them, there can be moments of joy, resolution and inspiration just as intense as those of fear, discomfort and sadness.

‘I am not redefining death, I am offering another way to perceive dying. I have been offered an opportunity to live every moment until there are no more moments for me to live and for that I will be eternally grateful.’

Sometimes people say the silliest things

Arguments against Brittany Maynard’s assisted suicide ignore her point of view on suffering

by Kelly Stewart

Brittany Maynard died earlier this month.

Diagnosed with incurable brain cancer at 29 and given six months to live, Maynard relocated to Oregon to take advantage of the state’s death with dignity law. The law permits “mentally competent, terminally ill patients with a prognosis of six months or less to live” to access, as Maynard describes it, “the medical practice of aid in dying.”

Maynard became an advocate and public face for the death with dignity movement. In an opinion piece for CNN and a widely viewed video, she describes the severity of her physical and emotional suffering, the comfort of knowing she can “end [her] dying process if it becomes unbearable,” and the importance of making that option available to people without the “flexibility, resources and time” that allowed her and her husband to relocate.

“Consistent life” Catholics have been some of Maynard’s most fervent critics. Pope Francis didn’t mention her by name but denounced the “false sense of compassion” that motivates death with dignity and abortion rights laws. Various other Catholic responses have characterized her death as evidence of the cheapening of human life; an act that denies the dying person’s responsibility to others; an affront to the dignity of dying people; or even a “slippery slope” that leads to eugenics and genocide. And consistently, Maynard’s Catholic and other Christian critics have appealed to the redemptive value of suffering.

Michael Sean Winters’ blog post “Brittany Maynard’s Suffering” is representative. He writes: “Christians must reclaim the ability to embrace suffering.” He offers a few caveats: We shouldn’t be masochists, and we should work to alleviate some forms of suffering, especially “those varieties of suffering in which we are complicit.” Still, he insists, “in the face of some experiences of suffering, we must never lose sight of the need to embrace it.”

For Winters, Maynard’s decision is fundamentally about a refusal to embrace suffering as meaningful — and, therefore, a refusal to acknowledge human finitude, vulnerability, and radical dependence on God. He characterizes this as a U.S. cultural as well as a generational problem. Children and young adults today, he suggests, have been sheltered from the raw experiences of pain and loss that accustomed earlier generations to the inevitability of suffering and instilled respect for its spiritual value.

For Winters, Maynard’s decision is fundamentally about a refusal to embrace suffering as meaningful — and, therefore, a refusal to acknowledge human finitude, vulnerability, and radical dependence on God. He characterizes this as a U.S. cultural as well as a generational problem. Children and young adults today, he suggests, have been sheltered from the raw experiences of pain and loss that accustomed earlier generations to the inevitability of suffering and instilled respect for its spiritual value.

Cathy Lynn Grossman’s blog post for Religion News Service “Does Suffering Have Spiritual Meaning?” takes a similar approach. Like Winters, Grossman frames the death with dignity question in terms of a spiritual vs. secular divide. The religious voices she includes in her article all oppose right-to-die laws: a Baptist woman whose teenage daughter has brain cancer, Popes Benedict XVI and John Paul II, and Jesuit Fr. Kevin Fitzgerald.

“When can we say that the potential to grow or overcome or bear that suffering, that potential which made that suffering meaningful, is gone forever?” she quotes Fitzgerald as saying. “Why do we think someone is enlightened enough to know their suffering is not redemptive?”

Grossman does not, however, spend much time on Maynard’s moral reasoning. Instead, she frames Maynard’s decision as a secular, perhaps youthful abandonment of serious reflection on suffering.

“Her choice to die,” Grossman writes, “may reinforce to many — particularly religiously-disengaged millennials — that spiritual meaning, like suffering, is up to you.”

Readings these responses, I have been struck by how tenaciously Maynard’s critics avoid engaging her actual arguments and how little detail they offer in support of their own positions.

They write moving personal reflections on the deaths of loved ones. They offer general tributes to the relationship between love and vulnerability and suffering. They incorporate a few laments about secularism and young adults. But their discussions of Maynard, the death with dignity movement, and even their own theologies of suffering seem to remain at a general level.

That’s a problem, because when we discuss a concept whose history is as ugly as that of “redemptive suffering,” it is irresponsible to be vague. When we discuss the Christian meaning of suffering, it is irresponsible to ignore decades of feminist, womanist, and postcolonial work on the problems with its valorization in Christian theology. And when an actual suffering and dying person tells us, “This is more than I can bear,” it is irresponsible and cruel to respond that she couldn’t possibly know that.

Before she died on Nov. 1, Brittany Maynard made a case for the right of terminally ill people to end their suffering quickly. She argued that no one else could say when her suffering became intolerable, when her life became unlivable, when her dignity was diminished, or how she was to face her painful and untimely death.

If you read her arguments, listen carefully to her experiences of illness, and maintain — from a position of relative health and safety — that Maynard should nonetheless have embraced her suffering as a redemptive experience, please be careful, suspicious of yourself, and painstakingly detailed in how you make that case.

Under what conditions is suffering redemptive? By what criteria do you distinguish suffering that should be alleviated from suffering that should be embraced? When should your theology of suffering be imposed on people who do not understand their suffering as redemptive? What are the consequences of doing that? What are the consequences of not doing that? Is the embrace of suffering as “countercultural” for others as it is for you? And how do you know you’re right?

These sorts of questions should guide discussions of Brittany Maynard’s death and activism. And they should make us very cautious about finding grace in someone else’s suffering.

Complete Article HERE!