Look for Part 1 and 2 of this series HERE and HERE!

1. Do what feels natural.

There’s no right or wrong way to die. For some people, it may be desirable to spend as much time with friends and family as possible, while others may find comfort in solitude, choosing to face things alone. Some people might want to kick up their heels and make the most of the last days, while others may want to go about the same basic routine.

- Don’t be afraid to have fun, or to spend your time laughing. Nowhere does it say that the end of life is supposed to be a somber affair. If you want to do nothing more than watch your favorite football team and joke with your relatives, do so.

- It’s your life. Surround yourself with the things and the people that you want to be surrounded with. Make your happiness, comfort, and peace your priority.[6]

2. Consider pulling away from your work responsibilities.

Few people receive a terminal diagnosis and wish they’d spent more time at the office, and one of the most common near-death regrets is of working too much and missing out. Try not to spend the time you have left, if there isn’t much, doing something you don’t want to be doing.

- It’s unlikely you’ll be making a marked financial difference for your family in a short amount of time, so focus on what will make a difference: addressing the emotional needs of yourself and your family.

- Alternatively, some people may find energy and comfort in going about the routine of work, especially if you’re feeling physically strong enough to do so. If it feels natural and reassuring to keep working, do it.

3. Meet with friends and loved ones.

One of the biggest regrets those who are facing death express is not staying in touch with old friends and relatives. Remedy this by taking the opportunity to spend a little time with them, one-on-one if possible, and catch up.

- You don’t have to talk about what you’re going through if you don’t want to. Talk about your past, or focus on today. try to keep things as positive as you want them to be.

- If you want to open up, do so. Express what you’re going through and release some of the grief you’re experiencing with people you trust.

- Even if you don’t have much energy for laughter or conversation, just having them sit by your side can bring you worlds of comfort.

- Depending on your family situation, it might be easier to meet with people in big shifts, seeing whole families at once, or you may prefer focusing on individual meetings. These have a tendency to help slow down time, focusing on quality, rather than quantity. This can be a great way of maximizing the time you have left.

4. Focus on unwinding your relationships. It’s common for those near death to want to uncomplicate complicated relationships. This can mean a variety of things, but it generally means trying to resolve disputes and go forward less burdened.

- Make an effort to end any fights, arguments, or misunderstandings so that you can move forward. You shouldn’t engage in arguments and keep fighting, but rather, agree to disagree when necessary and end your relationships on a good note.

- While you probably can’t be around the people you care about all of the time, you can plan to see them in shifts, so that you rarely feel alone.

- If you can’t see your loved ones in person, making a phone call to someone you care about can make a difference as well.

5. Decide how much you want to reveal.

If your health situation is unknown to your friends and family, you may elect to let everyone know what’s going on and keep them up to date, or you may prefer keeping things private. There are advantages and disadvantages to each choice, and it’s something you’ll have to decide for yourself.

- Letting people know can help you get closure and feel ready to move on. If you want to grieve together, open up and let your friends family in. You can tell them individually to make it feel more personal, and tell only those people that you really care about, or make it more public. This can make it difficult to avoid the issue and focus on lighter subjects over the next weeks and months, though, which is a negative for many people.

- Keeping your situation private can help to maintain your dignity and privacy, a desirable thing for many people. While this might make it difficult to share and grieve together, if you feel like this is something you want to take on alone, you might consider keeping it private.

6. Try keeping things as light as possible.

Your final days probably shouldn’t be spent pouring over Nietzsche and contemplating the void, unless you’re the sort of person who finds pleasure in these things. Let yourself experience pleasure. Pour yourself a glass of whiskey, watch the sunset, sit with an old friend. Live your life.

- When you face death, you don’t have to make an extra effort to come to terms with it. It will come to terms with you. Instead, use the time you have left to enjoy the people and things you enjoy, not to focus on death.

7. Be open with what you want from others.

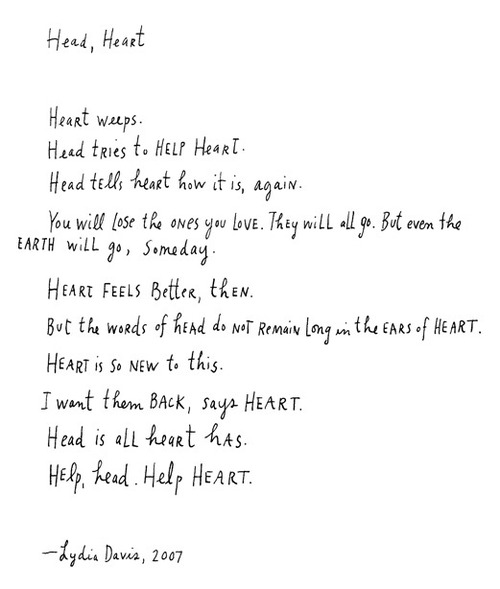

One thing you may have to deal with is the fact that the people around you are having trouble coping with your death. They may look even more upset, hurt, and emotional than you feel. try to be as honest as seems kind with your family, when discussing your feelings and desires.

- Though you may want nothing more from them than comfort, optimism, and support, you may find that they will be having trouble in their own grief. That’s perfectly natural. Accept that people are doing their best and that they’ll need a break sometimes, too. Try your best not to be angry or disappointed at how they’re reacting.

- You may find that some of your loved ones are showing little emotion at all. Don’t ever think that this means that they don’t care. It just means that they are dealing with your health quietly, in their own way, and that they’re trying not to upset you with how they feel.

8. Talk to a religious advisor, if necessary.

Talking to your pastor, rabbi, or other religious leader can help you feel like you’re less alone in the world and that there’s a path laid out for you. Talking to religious friends, reading religious scriptures, or praying can help you find peace. If you’re well enough to attend your church, mosque, or synagogue, you can also find peace by spending more time with people in your religious community.

- However, if you don’t subscribe to a religion, don’t feel compelled to change your mind and to believe in the afterlife after all if that’s not really true to who you are. End your life as you’ve lived it.

Complete Article HERE!