By David Marchese

A decade ago, Hadley Vlahos was lost. She was a young single mother, searching for meaning and struggling to make ends meet while she navigated nursing school. After earning her degree, working in immediate care, she made the switch to hospice nursing and changed the path of her life. Vlahos, who is 31, found herself drawn to the uncanny, intense and often unexplainable emotional, physical and intellectual gray zones that come along with caring for those at the end of their lives, areas of uncertainty that she calls “the in-between.” That’s also the title of her first book, which was published this summer. “The In-Between: Unforgettable Encounters During Life’s Final Moments” is structured around her experiences — tragic, graceful, earthy and, at times, apparently supernatural — with 11 of her hospice patients, as well as her mother-in-law, who was also dying. The book has so far spent 13 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. “It’s all been very surprising,” says Vlahos, who despite her newfound success as an author and her two-million-plus followers on social media, still works as a hospice nurse outside New Orleans. “But I think that people are seeing their loved ones in these stories.”

What should more people know about death? I think they should know what they want. I’ve been in more situations than you could imagine where people just don’t know. Do they want to be in a nursing home at the end or at home? Organ donation? Do you want to be buried or cremated? The issue is a little deeper here: Someone gets diagnosed with a terminal illness, and we have a culture where you have to “fight.” That’s the terminology we use: “Fight against it.” So the family won’t say, “Do you want to be buried or cremated?” because those are not fighting words. I have had situations where someone has had terminal cancer for three years, and they die, and I say: “Do they want to be buried or cremated? Because I’ve told the funeral home I’d call.” And the family goes, “I don’t know what they wanted.” I’m like, We’ve known about this for three years! But no one wants to say: “You are going to die. What do you want us to do?” It’s against that culture of “You’re going to beat this.”

Is it hard to let go of other people’s sadness and grief at the end of a day at work? Yeah. There’s this moment, especially when I’ve taken care of someone for a while, where I’ll walk outside and I’ll go fill up my gas tank and it’s like: Wow, all these other people have no idea that we just lost someone great. The world lost somebody great, and they’re getting a sandwich. It is this strange feeling. I take some time, and mentally I say: “Thank you for allowing me to take care of you. I really enjoyed taking care of you.” Because I think that they can hear me.

The idea in your book of “the in-between” is applied so starkly: It’s the time in a person’s life when they’re alive, but death is right there. But we’re all living in the in-between every single moment of our lives. We are.

So how might people be able to hold on to appreciation for that reality, even if we’re not medically near the end? It’s hard. I think it’s important to remind ourselves of it. It’s like, you read a book and you highlight it, but you have to pick it back up. You have to keep reading it. You have to. Until it really becomes a habit to think about it and acknowledge it.

I was reading these articles recently about how scientists are pursuing breakthroughs that could extend the human life span to one hundred twenty.1

1

Examples of which could include devising drug cocktails that get rid of senescent cells and filtering old blood to remove molecules that inhibit healing.

There’s some part of people that thinks they can cheat death — and, of course, you can’t. But what do you think about the prospect of extending the human life span? I don’t want to live to be 120. I have spent enough time around people who are close to 100, over 100, to know that once you start burying your children, you’re ready. Personally, I’ve never met someone 100 or older who still wants to be alive. I have this analogy that I did a TikTok2

2

Vlahos has 1.7 million followers on TikTok, where she posts about her experience as a hospice nurse and often responds to questions about death and dying.

on. This is from having a conversation with someone over 100, and her feeling is that you start with your Earth room when you’re born: You have your parents, your grandparents, your siblings. As you get older, your Earth room starts to have more people: You start making friends and college roommates and relationships. Then you start having kids. And at some point, people start exiting and going to the next room: the afterlife. From what she told me, it’s like you get to a point when you’re older that you start looking at what that other room would be, the afterlife room,3

3

According to a 2021 Pew Research survey, 73 percent of American adults say they believe in heaven.

and being like, I miss those people. It’s not because you don’t love the people on Earth, but the people you built your life with are no longer here. I have been around so many people who are that age, and a majority of them — they’re ready to go see those people again.

“The In-Between” also has to do with the experience of being in between uncertainty and knowing. But how much uncertainty is there for you? Because in the book you write about things that you can’t explain, like people who are close to death telling you that they’re seeing their dead loved ones again. But then you write, “I do believe that our loved ones come to get us when we pass.”4

4

From Vlahos’s book: “I don’t think that we can explain everything that happens here on Earth, much less whatever comes after we physically leave our bodies. I do believe that our loved ones come to get us when we pass, and I don’t believe that’s the result of a chemical reaction in our brain in those final hours.”

So where is the uncertainty? The uncertainty I have is what after this life looks like. People ask me for those answers, and I don’t have them. No one does. I feel like there is something beyond, but I don’t know what it is. When people are having these in-between experiences of seeing deceased loved ones, sometimes it is OK to ask what they’re seeing. I find that they’ll say, “Oh, I’m going on a trip,” or they can’t seem to find the words to explain it. So the conclusion I’ve come to is whatever is next cannot be explained with the language and the knowledge that we have here on Earth.

Do these experiences feel religious to you? No, and that was one of the most convincing things for me. It does not matter what their background is — if they believe in nothing, if they are the most religious person, if they grew up in a different country, rich or poor. They all tell me the same things. And it’s not like a dream, which is what I think a lot of people think it is. Like, Oh, I went to sleep, and I had a dream. What it is instead is this overwhelming sense of peace. People feel this peace, and they will talk to me, just like you and I are talking, and then they will also talk to their deceased loved ones. I see that over and over again: They are not confused; there’s no change in their medications. Other hospice nurses, people who have been doing this longer than me, or physicians, we all believe in this.

Do you have a sense of whether emergency-room nurses5

5

Who, because of the nature of their jobs, are more likely than hospice nurses to see violent, painful deaths.

report similar things? I interned in the E.R., and the nurse I was shadowing said that no one who works in the E.R. believes in an afterlife. I asked myself: Well, how do I know who’s correct? How am I supposed to know? Are the people in the church that I was raised with6

6

Vlahos was raised in an Episcopalian family. She now refers to herself, as so many do, as spiritual rather than religious

more correct than all these people? How are you supposed to know what’s right and what’s not?

But you’ve made a choice about what you believe. So what makes you believe it? I totally get it: People are like, I don’t know what you’re talking about. So, OK, medically someone’s at the end of their life. Many times — not all the time — there will be up to a minute between breaths. That can go on for hours. A lot of times there will be family there, and you’re pretty much just staring at someone being like, When is the last breath going to come? It’s stressful. What is so interesting to me is that almost everyone will know exactly when it is someone’s last breath. That moment. Not one minute later. We are somehow aware that a certain energy is not there. I’ve looked for different explanations, and a lot of the explanations do not match my experiences.

That reminds me of how people say someone just gives off a bad vibe. Oh, I totally believe in bad vibes.

But I think there must be subconscious cues that we’re picking up that we don’t know how to measure scientifically. That’s different from saying it’s supernatural. We might not know why, but there’s nothing magic going on. You don’t have any kind of doubts?

None. Really? That’s so interesting. You know, I read your article with the atheist.7

7

“How to Live a Happy Life, From a Leading Atheist,” an interview with the philosopher Daniel C. Dennett, published in August.

I feel like you pushed back on him.

There are so many things in our lives, both on the small and the big scale, that we don’t understand. But I don’t think that means they’re beyond understanding. OK, you know what you would like? Because I know that you’re like, “I believe this,” but you seem to me very interested; you’re not just set in your ways. Have you ever heard that little story about two twins in a womb?8

8

Known as the parable of the twins, this story was popularized by the self-help author Dr. Wayne W. Dyer in his 1995 book “Your Sacred Self: Making the Decision to Be Free.”

I’m going to totally butcher it, but essentially it’s two twins who can talk in the womb. One twin is like, “I don’t think that there is any life after birth.” And the other is like, “I don’t know; I believe that there is something after we’re born.” “Well, no one’s ever come back after birth to tell us that there is.” “I think that there’s going to be a world where we can live without the umbilical cord and there’s light.” “What are you talking about? You’re crazy.” I think about it a lot. Do we just not have enough perspective here to see what could come next? I think you’ll like that story.

For the dying people who don’t experience what you describe — and especially their loved ones — is your book maybe setting them up to think, like: Did I do something wrong? Was my faith not strong enough? When I’m in the home, I will always prepare people for the worst-case scenario, which is that sometimes it looks like people might be close to going into a coma, and they haven’t seen anyone, and the family is extremely religious. I will talk to them and say, “In my own experience, only 30 percent of people can even communicate to us that they are seeing people.” So I try to be with my families and really prepare them for the worst-case scenario. But that is something I had to learn over time.

Have you thought about what a good death would be for you? I want to be at home. I want to have my immediate family come and go as they want, and I want a living funeral. I don’t want people to say, “This is my favorite memory of her,” when I’m gone. Come when I’m dying, and let’s talk about those memories together. There have been times when patients have shared with me that they just don’t think anyone cares about them. Then I’ll go to their funeral and listen to the most beautiful eulogies. I believe they can still hear it and are aware of it, but I’m also like, Gosh, I wish that before they died, they heard you say these things. That’s what I want.

You know, I have a really hard time with the supernatural aspects, but I think the work that you do is noble and valuable. There’s so much stuff we spend time thinking about and talking about that is less meaningful than what it means for those close to us to die. I have had so many people reach out to me who are just like you: “I don’t believe in the supernatural, but my grandfather went through this, and I appreciate getting more of an understanding. I feel like I’m not alone.” Even if they’re also like, “This is crazy,” people being able to feel not alone is valuable.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity from two conversations.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Grieving Through Google

— After my dad’s cancer diagnosis, Google Translate became a tool for survival—and then, remembrance.

By Miun Gleeson

When my dad died, he became part of the cloud.

Not the one up high in the sky, but rather an online cumulus that now stores and archives a record of his last 18 months on earth. On my laptop, and even more prominently on my phone, I carry with me digital traces of my dad that I can’t yet bring myself to access. Four years after his death, I still sit with a kind of grief that remains more raw than residual, and his memory lingers in digital purgatory—undeleted yet untouched; saved but not sought. He “lives” in this liminal digital space; like a grave I can’t yet bring myself to visit, but simply know is there.

This notion of keeping my dad “close” is ironic, given that the experience of losing him was marked by deep distances. My dad and I lived 1,800 miles apart, he in California and I in Missouri. There was also linguistic distance between us, which was in many ways more difficult to bridge. As an American-born Korean, English had always been my first language, and I never really learned how to speak Korean. I did a short stint at Korean language school, where I learned the alphabet and mastered the preemptive explanation I’d have ready anytime I encountered another Korean person: “I understand better than I can speak.”

Despite having emigrated to the U.S. from Korea nearly 40 years ago, my dad similarly never mastered English. Even though my Korean fluency would surely have made his life easier, he never forced it when I was younger, which made him an outlier among many parents in our community who were raising bilingual first-generation children. As an adult, I asked my dad—with a mix of both surprise and gratitude—why he never mandated I learn Korean with the same insistence as so many other parents.

“Why I do? Because you born here and die here,” he answered.

Still, our bond was deep, enduring, and always made whole despite his broken English and my equally fractured Korean. We codeswitched and improvised; we asked and answered each other in both languages. My dad had his standbys and shorthand (“Did you eat yet?”) that expressed everything I ever needed to know about how much he loved me. Ours was a profound, implicit relationship that was strong enough to weather anything. Until it was put to the ultimate test.

When a loved one is dying, the learning curve is steep. There is a dense vocabulary of disease and little time to get up to speed. In need of a fast and familiar resource, I Googled my way through all the insidious ways cancer can destroy a liver and pages of impossible, vowel-laden medications.

But my dad and I required a two-step process as I assumed my role as language liaison with his medical team. I had to graduate to Google Translate, enlisting it to do what I could not as I learned how to convey bad news in two languages. I had never used Google Translate before and was relieved by its simple interface. Choose your languages, copy and paste. As they flashed on the screen, the translations themselves carried a certainty and confidence that the information they conveyed often lacked. I constantly toggled between English to Korean and Korean to English. Along the way, I acquired some new words in Korean, like bangsaneung for radiation and gan for liver. But even my latent knowledge of Korean surprised me at times, as I remembered the word for sadness, and even complete sentences: Appa, did you eat yet?

Clumsily, my dad and I did this dance for a while; me trying to facilitate care despite being geographically undesirable and culturally inept, never mind what I felt this long goodbye was personally inflicting on a molecular level. In the winter of 2017, when we were just six months past the initial diagnosis and learned that the cancer would most assuredly kill him by summer, my dad announced he was returning to his native Korea to die.

Why I do? Because I born there and die there.

Once my dad moved, the language barrier became even more difficult to manage with my non-English-speaking relatives, who had to now serve as my intermediaries. We were pivoting to long-distance death, shifting settings and reversing roles. My first phone calls to Korea to get updates were disastrous, as the seemingly simple act of communication became an impossible juggling act: talk, Google Translate, listen, Google Translate, don’t fall apart.

Desperate for a better way to communicate, I downloaded KakaoTalk. The free and widely popular Korean messaging platform (which also includes voice and video calls) was convenient—all of my family members were already on it, and as soon as I added my name and a profile picture of me and my dad, we quickly found each other.

Indispensable companion pieces, I used KakaoTalk in tandem with Google Translate. It was far from perfect, but we eventually established a clunky but workable communications cadence by relying primarily on the chat function. Those saved conversations through KakaoTalk also live in the cloud. But I have only revisited the translated transcripts with my aunts and uncles once, knowing that some of these halting, heart-wrenching exchanges will never truly leave me.

Is he okay? Why doesn’t he want me to come see him now? This is absolutely breaking me.

Your father doesn’t want you to remember him this way. He says you are his entire life.

For weeks, KakaoTalk and Google Translate were a lifeline to my dying dad. I carried an intense shame at having to use an online translation service to communicate both my personal and practical needs that final spring. But when I finally made it to Korea, I was embraced by my family’s tacit, touching love that could only be conveyed in person. My dad waited to die until I flew back to the States after a weeklong vigil. The news was fittingly relayed to me via KakaoTalk, 15 hours into the next day on the other side of the world. I flew back to Korea one final time for his funeral—janglye, Google Translate informed me. But the actual experience of saying goodbye defied easy translation.

I realize that it seems odd to hold on to this untouched electronic ecosystem of a period that was just terribly sad. I can’t help but see my archive of searches, translations, and conversations within these apps as personally damning. They lay bare my shortcomings, my faults, my too many questions, my one-minute-let-me-translate-this entreaties. They provoke a maelstrom of “ifs”: If I had lived closer, if I had been more Korean, if I had somehow been better prepared for the unthinkable so I didn’t have to rely on my phone to get me through this.

But there is another set of “ifs”: What if I didn’t have these technological supports? They did what they were supposed to on a pressing, practical level—educate, coordinate, confirm, translate, expedite, communicate. And even though I cannot yet click through it, this electronic ephemera also reinforces that my loss, largely experienced in an out-of-body haze, was very much real. It’s an untainted, technologically aided record that is available if and when I can revisit it.

I hold on to hope that the way I see this digital record could one day change—no longer as a personal indictment, but perhaps as evidence that I tried. Perhaps as a first step toward slowly forgiving myself. For now, it is a phantom presence hanging overhead, omnipresent and accessible at any time, a reminder that my dad is nowhere and everywhere all at once.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

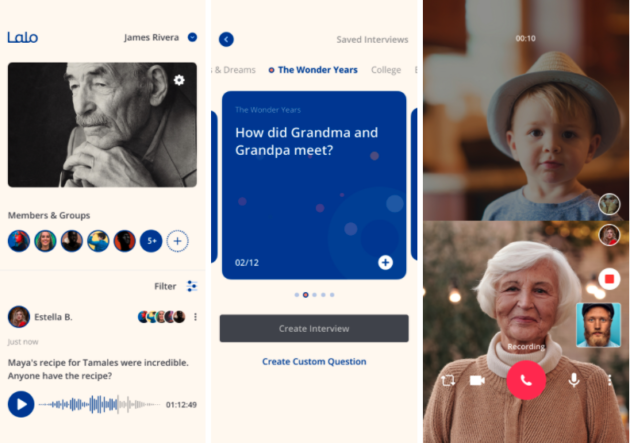

Seattle startup Lalo is latest ‘death tech’ innovator, with an app to share and collect stories and more

Juan Medina first considered the idea for his new startup back in 2003, after the death of his father, when his wife asked him to tell a story about his dad and Medina realized he hadn’t known him all that well. Stories, jokes, recipes and more were either lost or scattered across various friends and family, Medina said.

The idea resurfaced in the last couple years as Medina’s own daughter, now 9, said she never really met her grandparents. Medina decided to launch his startup Lalo — also his dad’s nickname — with the mission of giving people a private, digital space to connect, share stories and hold on to precious memories.

Currently operating as a small, private beta, Lalo is an app that facilitates the collection of digital content such as images, video, voice, text and more. Away from the noise and common pitfalls of traditional social media platforms, groups are intentionally kept small to foster increased trust and privacy. Imagine family members gathering to collect the best recipes in one space or share images that might have been lost to an unseen photo album.

“It’s a space to capture those more important family memories, the Sunday phone call from the grandkids to the grandparents where they can say, ‘Grandpa, tell me about a time … ,’ Medina said.

Lalo plans to make money by charging $25 a year for a subscription to the ad-free app, with multiple people being able to have access to a space for that price. Medina said the idea is optimized for smaller groups of 10 to 15 people and over-biased on privacy.

“You’re not going to get pinged by your middle-school friend, like, ‘Hey, join my account,’” he said.

Medina is also working on securing the permanence of the data, potentially with a blockchain solution or other ways to archive the material for the long, digital haul. He views his competitors as traditional social media such as Facebook where people are trading images and stories today, or more story-focused offerings such StoryCorps on NPR, or StoryWorth.

The idea brushes up against the wave of innovation falling into the “death tech” category, where startups are reimagining everything around traditional end-of-life and funeral industry practices with ideas involving body composting, cremation services and casket purchases.

Lalo users don’t have to focus on a recent or impending loss of a loved one, but Medina does believe the app can be a helpful tool in the grieving process.

Before trying his hand at his own startup, Medina spent a little over eight years at Amazon working on assorted tech, building things from scratch and understanding how to build things quickly. The decision to leave and start Lalo came with some apprehension.

“I’m married, I have a daughter, we have a mortgage. Walking away from that steady income that I’ve had my whole life was scary,” Medina said. “But it’s been amazing. I’ve loved it. It’s been great doing what I love, something I’m passionate about.”

And interest from different angel investors as well as funding from Lalo’s first institutional investor has eased some concerns about the long-term viability of the idea. Columbus, Ohio-based VC firm Overlooked Ventures announced earlier this month that Lalo was its first investment, and founding partner Janine Sickmeyer wrote of the startup, “No amount of technology can ease the pain of losing someone you love, but having better ways to grieve can help people cope and stay connected to mourn the loss together.”

Medina didn’t share how much money Lalo raised in pre-seed funding. The company incorporated at the end of 2020 and got moving in March after Medina left Amazon.

Lalo currently employs eight people and was among 30 startups selected for Washington Technology Industry Association’s sixth Founder Cohort Program, announced in August. The plan is to come out of beta in early 2022.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Four things you might not know about your digital afterlife

What happens to your data after you die?

1 Your digital footprint will one day become your digital remains

If a complete stranger were granted access to every scrap of recorded information about you that exists in the world, would they be able to stand up at your funeral and deliver a personal, moving eulogy that captured the essence of you? Thanks to the modern digital world, the likely answer is yes.

If you’re not active on social media, you might think that you’d be leaving behind very little in the way of a meaningful or personally telling digital legacy. Social media, however, are merely the tip of the little toe when it comes to our digital footprints. Anyone who has access to your devices and accounts after you die – including all the material you never intended to share – could tell quite a lot about you.

Formerly ephemeral communications are now comprehensively stored in searchable, time- and date-stamped emails and message threads. Once untrackable movements are logged by our smartphones, smartwatches, and facial recognition technologies in public spaces. Internet of Things (IoT) devices like video doorbells and virtual assistants are filling our homes.

And our internal desires, thoughts, and feelings can be discerned by innumerable others through our search histories, websites we’ve visited, and the documents and photos we store in cloud accounts and our data-storage devices.

Little wonder that the algorithms seem to know us better than we know ourselves – in this hyperconnected and electronically surveilled world, we are constantly feeding them our data.

A 2019 survey found that 1 in 4 people in the UK want all of these data to be removed from the internet when they die, but no legal or practical mechanisms exist for this to occur. There is no magical switch that is thrown, no virtual worms that traverse the internet nibbling away all traces of us when we die.

Physical death does not equal digital death. Our personal data is simply too voluminous, spread too far and wide throughout the digital world, and too under the control of innumerable third parties to simply call it back home to ‘bury’ it.

2 Social media are becoming digital cemeteries

Dedicated digital cemeteries do exist, the oldest being The World Wide Cemetery, founded in 1995, where people can still visit online graves and leave virtual flowers and tributes. Memorial gardens are dotted around the virtual world Second Life.

Many funeral homes now offer online condolence books, and some physical cemeteries even feature graves with digital components such as video screens or QR codes affixed to traditional headstones. Scores of digital legacy companies appear regularly, often going out of business shortly thereafter.

None of these digital cemeteries can hold a memorial candle, though, to the platforms that never intended to become online places of rest in the first place: sites like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Facebook has been memorialising profiles in one form or another since the Virginia Tech massacre in 2007, after which users pleaded with the site not to delete profiles that had become memorials for the lost.

Scholars at the Oxford Internet Institute have estimated that the number of deceased users on Facebook could be as high as 4.9 billion by 2100. The dead are also mounting up on Instagram, which also memorialises profiles, and Twitter may follow suit. In November 2019, Twitter cancelled an imminent inactive-account cull in response to an outcry from bereaved people who feared the loss of their deceased loved ones’ Twitter feeds.

Social media companies may be actively trying to work out what to do about the data of the deceased on their servers, but dead people’s information is all over the internet, across all sorts of websites and apps. Many – perhaps even most – of the entities that manage our data are not planning well for the end from the beginning, so information can stick around online for an indeterminate period of time.

We should never assume, however, that online is forever. Disappearance of online data is inevitable through deliberate culls, accidental data loss, and companies going bust.

3 People are struggling to make plans for their digital legacies

It’s not only organisations that are flummoxed by what to do about digital legacies. It’s us, the people who are accumulating them. Less than half of adults in the UK have made a traditional will, and far fewer have considered what will happen to their digital one.

In the Digital Legacy Association’s 2017 Digital Death Survey, 83 per cent of respondents had made no plans at all for their digital legacies. A handful of people – 15.2 per cent – had made their wishes known for their Facebook accounts using the Legacy Contact feature. Legacy Contact allows you to appoint a trusted person to manage your memorialised account after you die, and you can also stipulate if you want the account deleted.

Whether instructions left on Legacy Contact or any other online platform would hold up in UK courts, however, is another matter. As in many realms of modern life, this is an area where laws and regulations are not keeping pace with technology. GDPR and the UK’s Data Protection Act 2018 don’t comment on what should happen to the digitally stored information of the dead, who are no longer entitled to data protection.

Service providers are understandably reluctant to hand over account contents or access to next of kin, especially when that’s likely to compromise other (living) people’s privacy.

Laws governing wills and probate don’t help much either when it comes to digital material. To bequeath something to someone in the UK it has to be tangible or valuable, and your social media profiles might not be judged to be either. In addition, you can’t pass on what you don’t actually own in the first place.

You do not own your social media profiles. Even if you’d like to, you cannot pass on an iTunes or Kindle library, since you have only purchased a license to watch, listen or read while you’re alive. The vast majority of your online accounts and their contents are non-transferable: one account, one user.

It may be a while before coherent, enforceable systems are instituted to govern what should happen to the data of the deceased. Until then, the companies to whom we entrust our data when we’re alive largely decide what happens to it upon death and who can access it.

In this legal and regulatory void, we can only make arrangements as best we can. For sentimental and practical material that might be valuable to our loved ones, we need to leave behind instructions for how to access it or – even better – back it up in secure but accessible formats that are not under the control of online service providers. In the not-too-distant future, digital estate planning may be a career all its own, or at least a necessary component of an existing profession.

4 It is impossible to predict how digital legacies will be meaningful to the bereaved

Our expectations that ‘normal’ grief will follow predictable, orderly stages is encouraged by our algorithmic environment. If you type ‘stages of…’ into a search engine, that engine will likely suggestion completion with ‘grief’. If you type ‘grief’, the engine will likely suggest ‘stages of’.

Despite what you and the algorithms might think, however, bereavement is actually incredibly, spectacularly idiosyncratic. Just as every relationship we have in life is unique, each bereavement is particular too. Despite dominating the popular discourse for the latter half of the 20th Century, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ famous grief stages – which were actually based upon qualitative research done with dying people, not bereaved people – boast little empirical support.

Across cultures and millennia, people have continued bonds with their dead in various ways, and we cannot predict what digital artifacts will be important in helping a bereaved person feel a thread of connection to those gone before.

For every person that relies upon a memorialised Facebook profile in their grief, there will be another that wishes it would just disappear. A preserved Twitter profile might be an absolute lifeline to friends, but the family might want it removed, perhaps imagining it’s not important to anyone. There is no rule book for what should and should not be important to someone in grief.

An astonishing and unpredictable variety of digital artifacts have been reported to me as being sentimentally significant to bereaved people. The digital recording of her husband’s heartbeat, stored in iTunes on a widow’s phone. The way that a woman’s brother organised and named his files on his laptop, giving her a window into how he thought and reasoned. A spam email from a woman’s deceased friend whose account was hacked – even though she knew it came from a hacker, she didn’t want to erase it, because it was his name in her inbox. A mother’s search history on her laptop, revealing to her daughter what she was thinking about in the last days of her life.

And finally, Google Street View, haunted by those who are no longer at that address. There is dad, watering the front lawn. There is a fondly remembered pet, peeking out the window of the house. There is grandma, sitting on the porch where she always did, waiting for the school bus to bring her grandchildren home. Even Google Earth is full of ghosts.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

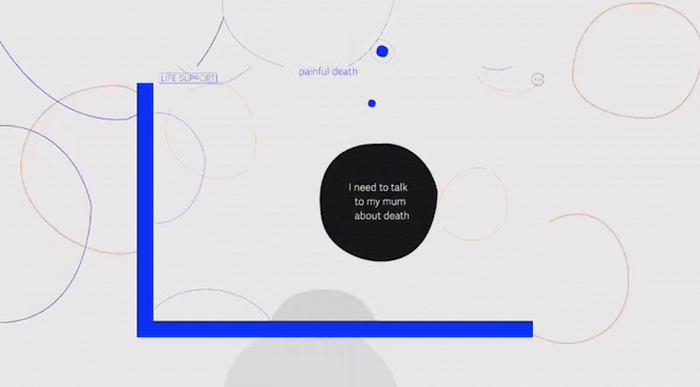

This empathic website helps you think and talk about death

Death is all around us this year. We need tools to help.

By Mark Wilson

It’s been a year of loss. But even seeing the devastation of COVID-19 hasn’t made it any easier to talk about death—and specifically, the possibility of our own deaths and deaths of those we love. Of course, ignoring death doesn’t make its inevitability any less real, during this year or any other.

Life Support is a new website from the London creative studio The Liminal Space, funded by the U.K. government. It’s a resource that proclaims, “Talking about dying won’t make it happen.” And with that premise as a baseline, it lets you explore topics about death and dying from the perspectives of experts, like palliative care doctors and social workers.

The design appears nebulous at first glance, with words floating in hand-drawn bubbles, which pulsate like the rhythm of your own breathing. But looks can be deceiving. What’s really lurking inside this casual space is a sharp curriculum built to answer your lingering questions about death.

As you scroll through the interface, the site offers several potential paths of thought that are probably familiar to most of us, like, “I’m scared to have a painful death” and “I don’t know if I should talk to my child about death.” When you find a question to explore, you swipe for more. That’s when experts come in. Some of their answers appear in blocks of text. Others are actually recorded, with audio you can play back. You might think the audio is a gimmick or unnecessary panache. In fact, I found it quite affecting to hear a doctor offering her own thoughts and advice about death aloud; it creates a level of intimacy that printed words can’t quite capture.

Ten or 20 years ago, a resource like this might have been a pamphlet (and indeed, anyone who frequents hospitals knows that pamphlets are still a mainstay to educate patients on topics of all types). But Life Support makes a convincing argument for how giving someone a bit of agency—like choosing our own questions to be answered, or hearing from doctors with our own ears when we’d like to—makes the information easier to digest.

I doubt there’s any quick resource out there that will ever get people completely comfortable talking or thinking about their own mortality. Religion and the arts have already attempted to tackle this topic for millennia. But Life Support is a solid attempt to ease us into the conversation.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

8 tips for understanding the ‘netiquette’ of death and grief

By Mark Ray

When Carla Sofka’s mother died just before Thanksgiving 2017, Sofka didn’t immediately post the news on social media. She was busy planning the funeral, making travel arrangements and getting an obituary ready for the weekly newspaper in her mother’s community.

“We had 23 hours to get the information to them if we didn’t want it to be 10 days before Mom’s obituary was in the local paper,” said Sofka, a professor of social work at Siena College in Loudonville, New York.

Then the phone rang.

Unbeknownst to Sofka, the funeral home had posted the obituary on its website, and almost immediately a childhood friend had spotted it and shared it on Sofka’s Facebook page.

“The minute that obituary showed up on my feed, people who saw it started posting comments and messages to me,” she said. “I didn’t even know this was going on, because I didn’t know it was there.”

What makes Sofka’s story ironic is that she has been writing and teaching about the impact of technology on grief and dying for decades. She even coined the term “thanatechnology” (“thana-” means death in Greek) in 1997. But in her moment of grief, she never thought to say to the funeral director, “Please don’t post Mom’s obituary on your website until we tell you that we’ve notified the people who need to find out another way.” (By the way, that funeral home now asks families whether posting is okay.)

Lee Poskanzer, CEO of Directive Communication Systems, which helps clients safeguard digital assets in their estates, experienced a more pleasant Facebook surprise in 2010 when he posted news of his mother’s death on Facebook.

“A very close friend of mine, who I would never have thought about calling, actually hopped on a plane and was able to make my mom’s funeral the next day,” he said.

The Social Media Rules Have Changed

As Poskanzer and Sofka’s stories illustrate, digital technologies have changed the rules surrounding grief and dying.

“How does one decipher a uniform approach when our society is using technology in so many diverse ways and each one of us has a different approach to our online presence and our digital footprint?” Poskanzer asked.

Fortunately, experts like Poskanzer and Sofka have begun answering those questions. While the landscape is still shifting, it’s possible to discern some basic rules of “netiquette.”

Here are eight tips about death and social media:

1. Leave the scoops to CNN and Fox News. If you’ve heard about a death but haven’t seen a Facebook post from the next of kin, that could be because family members are still trying to contact people who need to hear the news firsthand. Sofka said a good question to ask yourself is, “Is it your story to tell?”

2. Think before you post. Even when it’s appropriate to share, make sure what you’re sharing is appropriate. Don’t post painful or disturbing information without the family’s consent — and even then consider whether sharing is appropriate. “We may not recognize that we could be harming someone by posting or tweeting or putting a picture on Instagram,” Poskanzer said.

3. Avoid being cryptic. Nuance vanishes in cyberspace. A post that said “I’m praying for the Johnson family at this difficult time” could refer to anything from a death to a job loss to a house fire. “You have to know the poster in order to understand a little bit where they’re coming from,” Poskanzer said. When in doubt, pick up the phone.

4. Remember that news travels fast. When Sofka’s aunt died unexpectedly, she elected not to tell her teenage daughter, who was on vacation in Florida and didn’t know her great aunt well. Unfortunately, cousins began posting stories about the deceased woman on Facebook, so Sofka’s daughter quickly found out and wanted to know what was happening. “I can’t believe I didn’t expect that,” Sofka said.

5. Be patient. “Sometimes people watch how many people like a post or how quickly they acknowledge it,” Sofka said. “Somebody who’s grieving doesn’t have the time or energy to focus on that.” And if you’re on the other side of the situation, consider posting something like Sofka did after her mother’s passing: “I’m overwhelmed by the caring and the kindness of the postings. Please forgive me if I don’t have time to respond right now.”

6. Watch out for problems. Unfortunately, online death notices can attract everything from negative comments to fraudulent GoFundMe campaigns allegedly set up to pay for funeral expenses. “As family members and friends, if we see that, we need to contact the family immediately so somebody can contact GoFundMe,” Poskanzer said.

7. Be helpful — but not too helpful. It’s fine to offer to monitor the family’s online presence for problems, but don’t go too far. Poskanzer recalls a woman whose husband had just passed away. “While she was sitting shiva (mourning in the Jewish tradition), somebody had memorialized the page to her husband’s Facebook,” he said. As a result, the grieving woman no longer had access to the page. Facebook also has information about legacy contacts; people chosen in advance to oversee memorialized accounts.

8. Adjust your response to the situation. Poskanzer lost a friend recently who was very active on social media — to the point of chronicling her cancer battle online — so sending online condolences after she died made sense. On the other hand, Sofka talked with a woman who’s not active on social media and had recently lost her father. “She said, ‘Nobody sent cards; that was the hardest thing for me, because if felt like nobody cared,’” Sofka recalls.

As the rules of netiquette change — funeral selfies, anyone? — perhaps the best rule to follow is the Golden Rule: Blog, post and tweet about others as you would have them blog, post and tweet about you.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!