— After my dad’s cancer diagnosis, Google Translate became a tool for survival—and then, remembrance.

By Miun Gleeson

When my dad died, he became part of the cloud.

Not the one up high in the sky, but rather an online cumulus that now stores and archives a record of his last 18 months on earth. On my laptop, and even more prominently on my phone, I carry with me digital traces of my dad that I can’t yet bring myself to access. Four years after his death, I still sit with a kind of grief that remains more raw than residual, and his memory lingers in digital purgatory—undeleted yet untouched; saved but not sought. He “lives” in this liminal digital space; like a grave I can’t yet bring myself to visit, but simply know is there.

This notion of keeping my dad “close” is ironic, given that the experience of losing him was marked by deep distances. My dad and I lived 1,800 miles apart, he in California and I in Missouri. There was also linguistic distance between us, which was in many ways more difficult to bridge. As an American-born Korean, English had always been my first language, and I never really learned how to speak Korean. I did a short stint at Korean language school, where I learned the alphabet and mastered the preemptive explanation I’d have ready anytime I encountered another Korean person: “I understand better than I can speak.”

Despite having emigrated to the U.S. from Korea nearly 40 years ago, my dad similarly never mastered English. Even though my Korean fluency would surely have made his life easier, he never forced it when I was younger, which made him an outlier among many parents in our community who were raising bilingual first-generation children. As an adult, I asked my dad—with a mix of both surprise and gratitude—why he never mandated I learn Korean with the same insistence as so many other parents.

“Why I do? Because you born here and die here,” he answered.

Still, our bond was deep, enduring, and always made whole despite his broken English and my equally fractured Korean. We codeswitched and improvised; we asked and answered each other in both languages. My dad had his standbys and shorthand (“Did you eat yet?”) that expressed everything I ever needed to know about how much he loved me. Ours was a profound, implicit relationship that was strong enough to weather anything. Until it was put to the ultimate test.

When a loved one is dying, the learning curve is steep. There is a dense vocabulary of disease and little time to get up to speed. In need of a fast and familiar resource, I Googled my way through all the insidious ways cancer can destroy a liver and pages of impossible, vowel-laden medications.

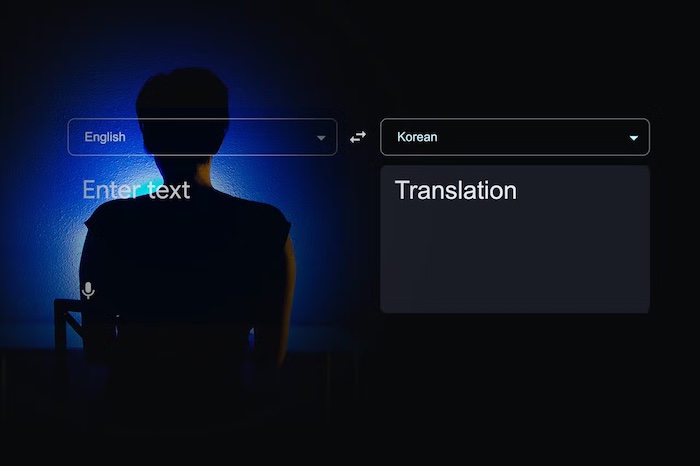

But my dad and I required a two-step process as I assumed my role as language liaison with his medical team. I had to graduate to Google Translate, enlisting it to do what I could not as I learned how to convey bad news in two languages. I had never used Google Translate before and was relieved by its simple interface. Choose your languages, copy and paste. As they flashed on the screen, the translations themselves carried a certainty and confidence that the information they conveyed often lacked. I constantly toggled between English to Korean and Korean to English. Along the way, I acquired some new words in Korean, like bangsaneung for radiation and gan for liver. But even my latent knowledge of Korean surprised me at times, as I remembered the word for sadness, and even complete sentences: Appa, did you eat yet?

Clumsily, my dad and I did this dance for a while; me trying to facilitate care despite being geographically undesirable and culturally inept, never mind what I felt this long goodbye was personally inflicting on a molecular level. In the winter of 2017, when we were just six months past the initial diagnosis and learned that the cancer would most assuredly kill him by summer, my dad announced he was returning to his native Korea to die.

Why I do? Because I born there and die there.

Once my dad moved, the language barrier became even more difficult to manage with my non-English-speaking relatives, who had to now serve as my intermediaries. We were pivoting to long-distance death, shifting settings and reversing roles. My first phone calls to Korea to get updates were disastrous, as the seemingly simple act of communication became an impossible juggling act: talk, Google Translate, listen, Google Translate, don’t fall apart.

Desperate for a better way to communicate, I downloaded KakaoTalk. The free and widely popular Korean messaging platform (which also includes voice and video calls) was convenient—all of my family members were already on it, and as soon as I added my name and a profile picture of me and my dad, we quickly found each other.

Indispensable companion pieces, I used KakaoTalk in tandem with Google Translate. It was far from perfect, but we eventually established a clunky but workable communications cadence by relying primarily on the chat function. Those saved conversations through KakaoTalk also live in the cloud. But I have only revisited the translated transcripts with my aunts and uncles once, knowing that some of these halting, heart-wrenching exchanges will never truly leave me.

Is he okay? Why doesn’t he want me to come see him now? This is absolutely breaking me.

Your father doesn’t want you to remember him this way. He says you are his entire life.

For weeks, KakaoTalk and Google Translate were a lifeline to my dying dad. I carried an intense shame at having to use an online translation service to communicate both my personal and practical needs that final spring. But when I finally made it to Korea, I was embraced by my family’s tacit, touching love that could only be conveyed in person. My dad waited to die until I flew back to the States after a weeklong vigil. The news was fittingly relayed to me via KakaoTalk, 15 hours into the next day on the other side of the world. I flew back to Korea one final time for his funeral—janglye, Google Translate informed me. But the actual experience of saying goodbye defied easy translation.

I realize that it seems odd to hold on to this untouched electronic ecosystem of a period that was just terribly sad. I can’t help but see my archive of searches, translations, and conversations within these apps as personally damning. They lay bare my shortcomings, my faults, my too many questions, my one-minute-let-me-translate-this entreaties. They provoke a maelstrom of “ifs”: If I had lived closer, if I had been more Korean, if I had somehow been better prepared for the unthinkable so I didn’t have to rely on my phone to get me through this.

But there is another set of “ifs”: What if I didn’t have these technological supports? They did what they were supposed to on a pressing, practical level—educate, coordinate, confirm, translate, expedite, communicate. And even though I cannot yet click through it, this electronic ephemera also reinforces that my loss, largely experienced in an out-of-body haze, was very much real. It’s an untainted, technologically aided record that is available if and when I can revisit it.

I hold on to hope that the way I see this digital record could one day change—no longer as a personal indictment, but perhaps as evidence that I tried. Perhaps as a first step toward slowly forgiving myself. For now, it is a phantom presence hanging overhead, omnipresent and accessible at any time, a reminder that my dad is nowhere and everywhere all at once.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!