Friends and relatives now join online campaigns to cover expenses

By Jodi Helmer

When someone dies, it’s common to send flowers or make a charitable donation in his or her honor. But a growing number of mourners are turning tocrowdfunding sites specially designed to help cover the deceased’s funeral expenses.

“Most people don’t plan their funerals in advance and that leaves their loved ones figuring out how to cover the costs,” explains Michael Blasco, spokesperson for YouCaring, a two-year-old crowdfunding platform for medical and memorial fundraising.

Funerals Often Exceed $7,000

With the average funeral now topping $7,045, according to the National Funeral Directors Association, families often find that saying goodbye to their loved ones comes with a higher price tag than they anticipated. Enter crowdfunding.

Once the provenance of entrepreneurs and artists (think Kickstarter and Indiegogo), crowdfunding lately has gained traction as a means for fundraising for a range of causes, including funeral expenses. Organizers post their campaigns online and seek funding from backers to meet their goals. The average campaign lasts between 30 and 60 days and the money raised is transferred to organizers via PayPal or WePay accounts.

Funeral campaigns can be set up through traditional crowdfunding sites such asYouCaring, Indiegogo, GoFundMe and GiveForward. But in the past two years, niche sites, such as Funeral Fund and Graceful Goodbye have also sprung up.

Raising $10,000 in a Funeral Crowdfunding Campaign

GoFundMe is currently hosting more than 8,000 funeral campaigns. On Indiegogo, over 50 funeral campaigns reached their fundraising goal, including a handful that raised upwards of $10,000 apiece. Funeral fundraising is the fastest-growing category on GiveForward, growing an average of seven percent per month.

“A lot of campaigns start out as medical fundraisers and then transition into funeral and memorial fundraisers [when the person dies],” explains Ariana Vargas, director of business development for GiveForward.

Joshua Starnes created a campaign on Funeral Fund after his friend, fellow film critic Eric Harrison, died of a brain aneurysm at 57 in 2012. Harrison, who was single and childless, didn’t have life insurance and there were no proceeds from his estate to cover funeral expenses. His young nieces were left to come up with the funds for his burial.

“Putting together even a modest funeral would have been impossible for them and [his colleagues] didn’t have enough cash in our group bank account to cover the cost,” says Starnes.

Crowdfunding, Starnes decided, was the best option. Thanks to the generosity of 108 backers, he collected $6,520 during the 30-day campaign — enough to cover the cost of the funeral.

A Kind and Innovative Technique

Crowdfunding consultant Rose Spinelli isn’t surprised that mourners are using this innovative technique to subsidize funeral expenses.

“In the most basic terms, crowdfunding is a community-building mechanism that brings people together around a cause,” says Spinelli, founder of The CrowdFundamentals site. “It can be a wonderful, warm feeling to know that people care and are sharing in the grief.”

But shared grief might not be enough to turn mourners into donors and crowdfunding efforts for older adults can be especially challenging. Many people in their 60s, 70s and 80s believe their cohorts should be prepared for their passing, with savings or prepaid funeral arrangements.

“People are willing to come forward with support when something unexpected happens,” Spinelli says. “When an older person dies, it doesn’t trigger the same reaction.”

Some Donors Get Thank-You Gifts

To boost response rates and honor backers who help with funeral costs, some crowdfunding organizers offer small tokens of appreciation. One Indiegogo campaign offered a handmade remembrance bracelet in exchange for a $25 contribution; another promised backers who pledged $50 that they’d receive a hug.

Blasco encourages posting photographs and favorite anecdotes about the deceased on the campaign page to increase the odds of crowdfunding success. “People respond to stories,” explains Blasco.

But even the most compelling stories are not apt to attract the attention of generous strangers, however. Instead, most contributions will come from relatives and friends.

For example, most who contributed to Starnes’ crowdfunding campaign for Harrison were relatives, former colleagues and patrons of the arts who appreciated the critic’s work. “The funds came from people he had an effect on in his life,” says Starnes.

What a Crowdfunding Campaign Costs

A crowdfunding campaign can also turn into an online memorial, a place for loved ones to share special memories and connect with others in a shared grief.

“The original intent and purpose [of a funeral crowdfunding campaign] is to raise money but, in a dark time, it’s also a place to celebrate a loved one’s life,” says Vargas. “It brings people together from all over the country who can’t make it to the funeral but want to say goodbye.”

In a time of grief, some mourners might not read the fine print in a crowdfunding campaign for a funeral. Fees vary, but crowdfunding sites typically keep three to 10 percent of the money raised.

And if you plan to launch a crowdfunding effort for a funeral or will donate to one, be sure you’re aware of the tax rules.

Quin Christian, an accountant with CrowdfundCPA, says crowdfunding contributions to help cover funeral expenses are likely to be considered gifts and shouldn’t be taxable to organizers.

Be careful, though. Christian warns that a gold-plated coffin, towering tombstone or designer burial suit — or even hosting multiple funeral-related crowdfunding campaigns in a short period of time — could raise IRS red flags.

Donors can’t write off what they give to a crowdfunding campaign as charitable contributions unless the beneficiary is a nonprofit.

But the benefit of using crowdfunding to cover funeral costs usually has nothing to do with the bottom line. “I’m glad we were able to help make sure he [Eric Harrison] had a proper burial,” says Starnes.

Complete Article HERE!

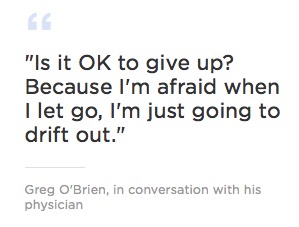

Over the past year, I’ve experienced several losses that, at the request of the deceased, did not include funerals. Grief rituals are central to my mourning process, but there’s no negotiating with the dead. In the absence of the most standard of ceremonies, how do you give expression to your grief while respecting someone’s final wish for “no funeral, please?” Through personal experience, and conversations with friends and readers who’ve faced the same scenario, here are seven ways to do just that.

Over the past year, I’ve experienced several losses that, at the request of the deceased, did not include funerals. Grief rituals are central to my mourning process, but there’s no negotiating with the dead. In the absence of the most standard of ceremonies, how do you give expression to your grief while respecting someone’s final wish for “no funeral, please?” Through personal experience, and conversations with friends and readers who’ve faced the same scenario, here are seven ways to do just that.